Americans don’t trust the media. We have the polling data, the bar graphs, the exasperated editorials to prove it. The Gallup survey numbers tell the story in neat, depressing symmetry: one-third of the country has “no trust at all,” another third has “not very much,” and the final third—God bless their optimism—still has “a great deal” or “fair amount” of trust left to give.

This should be a dead issue. In theory, when trust in a product falls this low, you either fix the product or abandon it. But in practice, our political class has decided that what the media really needs isn’t reform, transparency, or accountability—it’s an embedded “bias monitor” assigned by the government, like a parole officer for newsrooms.

And not just any newsroom—this is CBS News, a national outlet that, love it or loathe it, sits squarely in the “mainstream media” category. This monitor is the spawn of a corporate merger blessed by the Federal Communications Commission, under terms so strange they sound like they were drafted in a satire writer’s fever dream. The FCC said yes to the merger, but only if CBS agreed to accept an “ombudsman” tasked with rooting out bias.

The Trojan Hall Pass

FCC Chairman Brendan Carr, a Republican, dressed the idea in the rhetoric of oversight and fairness. FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez, the lone Democrat on the commission, called it out for what it is: a government-sanctioned “truth arbiter.” Both are technically correct, which is the most dangerous kind of correct.

On paper, an ombudsman sounds like a neutral party—someone who ensures journalists don’t run afoul of ethical standards. In reality, the position is defined by whoever writes the job description. And in this case, that’s the FCC. The same FCC whose members are appointed through a process drenched in partisan calculation.

Imagine hiring a babysitter and letting your ex’s divorce lawyer write the rulebook.

First Amendment with Training Wheels

The First Amendment isn’t complicated. It’s the radical, stubbornly clear principle that the government shall make no law abridging the freedom of the press. The founders didn’t include a footnote about “unless the press gets uppity” or “unless public opinion polls dip below 40 percent.”

Yet here we are—setting the precedent that the government, through a regulatory body, can install someone in a newsroom to watch for the wrong kind of thinking. The fact that this is happening in the context of a private corporate merger makes it worse, not better. Because now it’s not even purely governmental overreach—it’s corporate collusion in government overreach.

It’s not the state marching in to shut down the printing presses; it’s the state telling the press, “We’re just going to send a friend to sit in the corner and watch you type.”

Trust Through Surveillance

Proponents argue that this is about restoring trust. If people see there’s a bias monitor in the room, they’ll feel more confident the news is fair.

That’s not how trust works. Trust isn’t built by proving you can operate under surveillance—it’s built by proving you don’t need surveillance in the first place.

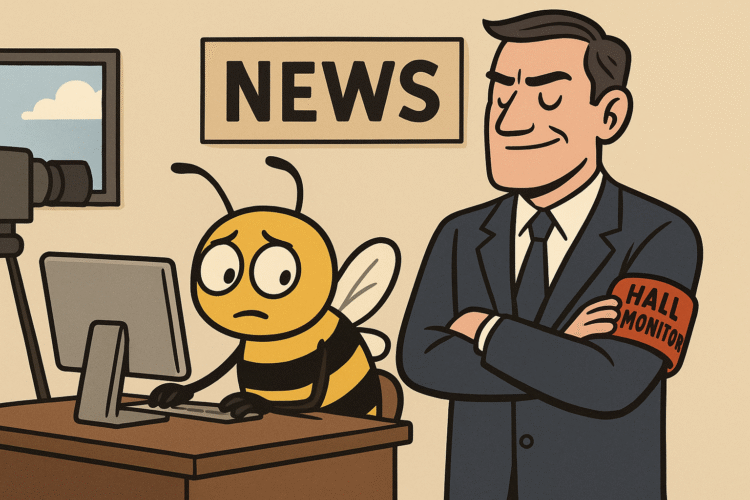

Slapping a government-approved hall monitor into a newsroom doesn’t remove bias; it adds a new one. Now, every editorial decision will carry the quiet awareness that it must pass the smell test of the person with the clipboard in the corner. And no matter who that person is—right-leaning, left-leaning, or a perfectly symmetrical centrist—they are still an external force with the power to influence content.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

The best-case scenario is that this bias monitor does nothing—sits there quietly, collects a paycheck, and becomes another line item in the ledger of useless bureaucratic inventions.

The worst-case scenario is that they become the newsroom’s gravitational center. Reporters start self-editing before the editing even begins. Producers start asking, “How will the monitor see this?” instead of, “Is this the truth?” And management begins to realize that pleasing the monitor can have advantages when it comes to corporate relations with the FCC.

This is how self-censorship metastasizes—quietly, politely, without a single overt act of suppression.

The False Neutrality Problem

Even if you believe in the idea of monitoring bias, the question becomes: whose definition of bias? In journalism, “bias” can mean anything from factually inaccurate reporting to simply covering an issue too much for someone’s liking. And when the monitor is approved in a political context, you can be sure the definition will lean in the direction that benefits those in power.

Which means the FCC, today under one political balance and tomorrow under another, could have the ability to decide which viewpoints require “correction.” This should terrify everyone, regardless of political affiliation.

It’s easy to imagine the outrage if the party you oppose were given the power to screen and adjust your news in real time. The harder part is admitting that the outrage should be identical when your own side is holding the pen.

The Slippery Slopes Are Greased

The precedent here isn’t subtle. If CBS accepts this condition without an all-out legal fight, it tells every other media outlet: yes, you can make deals that come with built-in ideological oversight, and it will be considered legitimate regulation.

From there, it’s a short slide to government monitors embedded in any newsroom that wants access to broadcast licenses, subsidies, or merger approvals. It’s also not hard to imagine a future where tech companies face similar demands—algorithms vetted by a government-approved “fairness inspector” before they can operate at scale.

Once you accept the principle that the government has a role in deciding whether the press is “balanced,” you’ve accepted the principle that the government has a role in deciding what the press says.

The Gaslight Strategy

One of the more insidious aspects of this situation is how it’s framed as a defense of the audience. You don’t trust the media? Great news—the FCC is here to make sure they’re fair to you.

This reframing takes legitimate criticism of corporate media and turns it into a weapon against the concept of a free press itself. It conflates “I don’t like what they say” with “They should have a government minder to make sure they don’t say it again.”

It’s like responding to bad restaurant reviews by assigning every chef a federal sous chef who checks the seasoning before the plate leaves the kitchen.

The Public’s Role in This

Americans are notorious for defending freedoms in the abstract while quietly trading them away in the specific. This is how we end up with policies that would have sounded like authoritarian fever dreams a decade ago, now being implemented with a shrug.

The calculation is simple: most people don’t like or trust the media, so they won’t rally to defend it against intrusion. It’s the same tactic used when governments target unpopular groups first—it’s easy to strip rights from people the public already dislikes.

But rights are structural, not personal. Once you accept that a bias monitor is okay for CBS because you dislike CBS, you’ve accepted that it’s okay for any outlet when it’s your turn to be on the receiving end.

Why This Matters Beyond the Media

The principle at stake here applies to every institution that relies on independence to function—universities, nonprofits, courts. The minute you accept that an external authority can dictate the boundaries of thought in one sector, you’ve set the template for all of them.

Today it’s the FCC installing a monitor in a newsroom. Tomorrow it’s the Department of Education installing one in a lecture hall. The day after, it’s the judiciary approving one for your lawyer’s office “to ensure fairness.”

In Conclusion

The beauty—and the danger—of the First Amendment is that it protects the press even when the press is bad at its job. Even when it’s biased, sloppy, arrogant, or out of touch. Especially then. Because the alternative is a press that is only allowed to be “good” according to the standards of the people in power.

The FCC’s bias monitor may seem like a small thing—a bureaucratic condition in a corporate deal that doesn’t affect your daily life. But freedoms rarely vanish in dramatic sweeps; they go one clause at a time, one oversight mechanism at a time, one “this won’t affect you” at a time.

And if we let the state install itself as a hall monitor for journalism, we’ll wake up one day to find that the newsroom door is locked from the outside—and the key isn’t in the hands of anyone we elected.