The wind in the high desert of Victorville, California, blows with a specific, sand-blasting indifference. It strips the paint off cars and the hope off human beings with equal efficiency. In this desolate landscape sits the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, a facility that sounds like a place where one might go to renew a driver’s license or file a tax return. The name suggests bureaucracy, paperwork, the dull hum of administrative efficiency. It is a masterpiece of euphemism. In reality, Adelanto is a concrete box run by the GEO Group, a corporation listed on the New York Stock Exchange, where the primary product is human misery and the latest quarterly earnings report is written in the obituary section.

We are currently witnessing the grim, industrial scaling of Donald Trump’s mass deportation machine, and Adelanto has emerged as its flagship franchise. It is the boutique experience for the detainee who wants to understand exactly how little their life is worth to the United States government. In September, Ismael Ayala Uribe, a thirty-nine-year-old man who once held DACA status—meaning the government had previously vetted him, fingerprinted him, and decided he was safe to live here—died in custody. He didn’t die in a prison riot. He didn’t die in a daring escape attempt. He developed a cough and a fever. In the free world, this is a trip to Walgreens. In Adelanto, it is a death sentence.

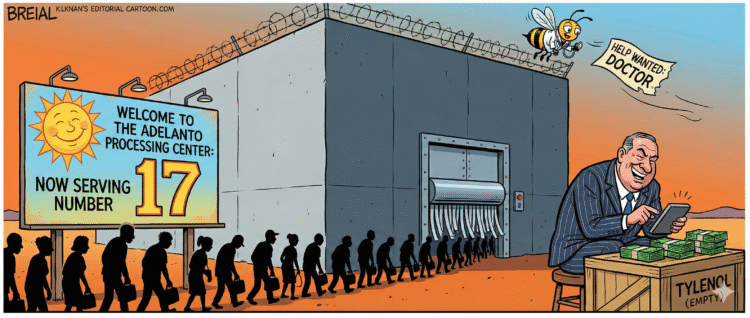

His death, followed closely by the death of another Orange County man, Huabing Xie, at the Imperial Regional Detention Facility, has pushed the nationwide toll in ICE custody to at least seventeen people in under a year. This is the highest number since the agency began publishing death data in 2018. It is a statistical spike that would trigger a shutdown in a meatpacking plant or a recall for a brand of spinach. But in the business of “civil detention,” it is apparently just the cost of doing business.

The government, for its part, is handling this crisis with the transparency of a lead wall. ICE officially admits to only fifteen deaths. The agency has failed to update its own tracking page, presumably because the webmaster is too busy helping to scout locations for the new tent cities they plan to erect with their fresh forty-five billion dollars in funding. The discrepancy in the numbers—the two missing bodies—is not a clerical error. It is a philosophy. It is the bureaucratic erasure of human beings who have ceased to be profitable assets for the private prison industry and have become, instead, liabilities to be minimized.

Ismael Ayala Uribe was picked up by immigration agents in August. He was healthy enough to be arrested. He was healthy enough to be processed. Yet, within weeks, the medical apparatus of Adelanto—a system that has been the subject of damning reports, lawsuits, and screams for help for years—failed him completely. A cough. A fever. These are the symptoms that killed him. We are sending people to Mars, but we cannot figure out how to keep a thirty-nine-year-old man alive when he gets the flu in government custody.

The situation is so dire that more than forty members of Congress, including fifteen from California, have signed a letter demanding answers. They want to know about the deteriorating conditions. They want to know about the inadequate health care. They want to know why the internal investigations into these deaths are opaque black holes that never lead to accountability. These are the same members of Congress who vote on the budgets that keep the lights on at GEO Group, writing sternly worded letters to a monster they continue to feed. The Department of Homeland Security receives the letter, files it, and continues the work of processing the next batch of inventory.

Adelanto is not a new problem. It is a legacy institution of suffering. It is a nearly two thousand-bed facility with a history that reads like a horror anthology. We are talking about a place with a documented record of suicides. We are talking about a facility where detainees went on hunger strikes to protest conditions and were met with force-feeding tubes, a practice that the United Nations generally frowns upon but which the for-profit prison industry views as a necessary medical intervention to protect the asset. We are talking about toxic chemical exposure and COVID outbreaks that tore through the population like wildfire in a dry canyon.

State attorney general inspections have issued damning reports that would shutter a dog kennel, yet Adelanto remains open. It remains open because it is essential. It is essential to the myth that this is “civil” detention. The government insists that these people are not being punished. They are merely being held. They are in an administrative limbo while their cases are adjudicated. But if you are locked in a cell, denied medical care, fed food that is barely edible, and cut off from your family, the distinction between “civil detention” and “prison” is purely semantic. If you die there, the funeral is the same.

The death of Huabing Xie adds another layer to the tragedy. He died after a reported seizure at the Imperial facility, another outpost in the archipelago of detention centers that ring the southern border. The pattern is undeniable. We are looking at a systemic collapse of the duty of care. When you detain thousands of people, you assume responsibility for their lives. You become their doctor, their landlord, and their guardian. The United States government, specifically ICE, has decided that it prefers the role of the slumlord.

The context here is the massive expansion of the system. The Trump administration has secured roughly forty-five billion dollars in new funding for border enforcement and detention. This money is not going to hire doctors. It is not going to improve the ventilation in the cells. It is going to expansion. They are racing to build tent camps. They are scouting military bases to use as overflow holding pens. They are tightening access for outside advocates, making it harder for lawyers and human rights observers to get inside and see what is happening.

This is the “infrastructure week” we were promised. We are building a massive, sprawling infrastructure of confinement. And as the system expands, the cracks in the medical care system are widening into chasms. The “shadow punishment system” is growing. It is a parallel legal universe where the Constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment are treated as suggestions rather than mandates. In this world, a person can be locked up for months or years without ever being convicted of a crime. They can rot in a cell because they overstayed a visa or crossed a line on a map.

The private prison giants like GEO Group are the primary beneficiaries of this expansion. Their stock price is a direct index of the deportation volume. Every bed filled is a revenue stream. Every day a detainee spends in custody is a line item on an invoice sent to the Treasury. There is a perverse incentive structure at play here. If you spend money on expensive medical care for a detainee, you hurt the margin. If you transfer them to a hospital, you incur costs. The most efficient way to run a private prison is to do the bare minimum required to keep the heart beating, and sometimes, as we have seen seventeen times this year, they miss even that low bar.

The disconnect between the “civil” label and the lethal reality is the core of the satire, if you can call it that. It is a dark, biting irony. We tell ourselves we are a nation of laws, a beacon of human rights. Yet we pay a corporation to warehouse human beings in the desert until they die of a fever. We allow the agency responsible for these deaths to edit the scoreboard, leaving bodies off the count because they haven’t gotten around to updating the website. We force families to learn about the death of their loved ones from local reporters because the government that held them can’t be bothered to make the call.

This is the machinery of the state stripped of its humanity. It is a system where the “process” is more important than the person. Ismael Ayala Uribe was “processed” into custody. He was “processed” through the medical unit. And finally, he was “processed” into a morgue. The paperwork was likely impeccable. The forms were all signed in triplicate. The only thing missing was the medicine that would have saved his life.

As the administration ramps up its deportation efforts, as the raids increase and the buses fill up, places like Adelanto will become even more crowded. The pressure on the already failing medical systems will increase. The death toll will rise. And the press releases from ICE will continue to use the passive voice. “A detainee passed away.” As if they simply decided to stop living, as if the environment and the neglect had nothing to do with it.

We are watching the normalization of death in custody. We are reaching a point where seventeen dead bodies are just a statistic to be managed, a PR problem to be spun. The outrage from Congress is necessary, but it feels performative in the face of the juggernaut. The letters are sent, the press conferences are held, and the wind in Victorville keeps blowing against the concrete walls of the processing center, where the next Ismael is coughing in his bunk, wondering if anyone is coming to help.

The answer, increasingly, is no. The doctor is not coming. The lawyer is barred at the gate. The advocate is shouting from the parking lot. Inside, the machine hums along, efficient, profitable, and deadly. The “civil detention” system is working exactly as designed. It is designed to break people. It is designed to make them disappear. And sometimes, if they are unlucky enough to get a fever in September, it makes them disappear forever.

The Part They Hope You Miss

The most haunting detail of the Ismael Ayala Uribe story is not the fever, but the silence. When someone dies in the care of the state, there is supposed to be a reckoning. There is supposed to be an immediate, transparent accounting of what went wrong. Instead, we have a system where the news trickles out through leaks and local reporting. The families are often the last to know the full truth. They are left to piece together the final moments of their loved ones from redacted reports and whispered phone calls from other detainees.

This information blackout is not an accident; it is a strategy. By controlling the flow of information, ICE controls the narrative. They prevent the public from seeing the full scale of the negligence. They keep the reality of Adelanto hidden behind the euphemism of “processing.” If we saw the video footage, if we heard the audio of the calls for help, the illusion of “civil detention” would shatter. So they keep the doors locked, they keep the records buried, and they count on the fact that most Americans will never look closely enough to see the bodies piling up in the desert. The silence is the wall they built long before they laid a single brick on the border.