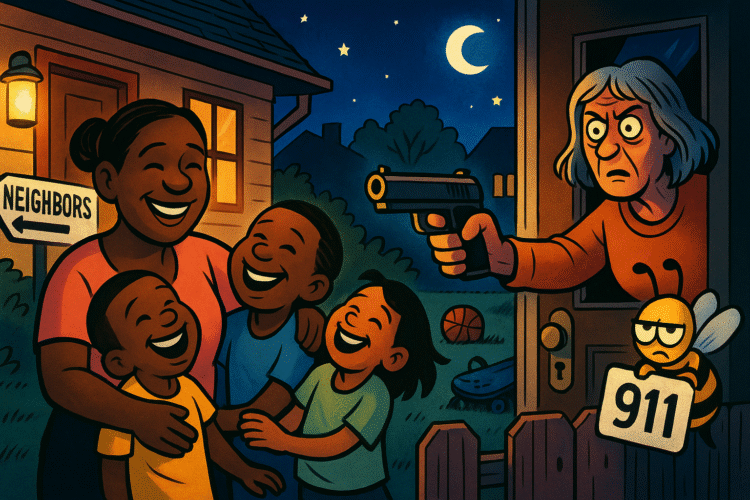

There’s a palpable hum in the night of suburban America—the 21st-century soundtrack of kids laughing under street-lamps, sprinklers buzzing, and the infinite ping of Ring-cams catching everything except the lives they claim to protect. In The Perfect Neighbor, directed by Geeta Gandbhir, this quiet suburban soundtrack becomes acoustic evidence of paranoia. The film chronicles a Florida neighborhood drawn into the orbit of a white woman, Susan Lorincz, who obsessively called the police on Black children, and who, on June 2 2023, shot and killed Ajike “AJ” Owens through a dead-bolted door in Ocala.

What happens next isn’t simply a murder documentary—it’s a deconstruction of our modern civic contract. Body-cam footage glides through two years of tension, as pre-pandemic neighborhood ties, children calling each other “mine,” and grass-lot football games collide with pandemic isolation, racial adultification bias, and the lethal architecture of Florida’s Stand Your Ground law. The result: one story of mutual care, another of privatized fear—an existential test of the small-town promise that we uphold one another or we obliterate one another.

When the Neighborhood Says “They’re All Mine”

There’s a scene in the film where a neighborhood mother—children running behind her, bicycles leaning against porches—looks into the camera and says, “They’re all mine.” Not just her kids, but all the kids. The property line becomes shared air; the sidewalk becomes playground and commons. That line is the sweet spot of civic life: belonging. Gaunt but real.

That moment kills the romantic line that America’s neighborhoods are shattered. The terrain of suburban fragmentation still houses trust, still knows everybody’s business, still launder lives in front yards and next-door porches. When that trust vanishes, you don’t just lose playtime—you lose public life.

But in Lorincz’s narrative, the neighbor system didn’t just collapse—it weaponized. She didn’t just call on the police once; she logged dozens of calls. She considered the kids’ skateboards as assault-weapons in the parking lot of her mind. The vacant lot beside her house, which should have held grass and summer nights, became an intrusion sensor in her head.

The contrast could not be sharper: one side built mutual accountability, the other built private surveillance. One side said “the kids are ours”; the other side said “the kids are your problem.” That pivot is where fear becomes doctrine.

The Dead-Bolt Door and the Doctrine of Self-Defense

Lorincz’s fatal trigger sits under the legal canopy of Florida’s Stand Your Ground law—a statute that removes the duty to retreat and allows deadly force when you feel threatened. In practice, this doctrine disproportionately favors white shooters who believe they are under siege by Black victims.

What The Perfect Neighbor does with body-cam footage is cruelly elegant. You watch decades of small infractions—kids yelling, roller skates on driveways, a playground next door—escalate into gunfire. The transverse path: childhood → trespass complaint → 911 call → bullet. The specific moment of killing is un-filmed, but the architecture of fear is visible. The locked door, the raised phone, the record of prior calls.

When Lorincz said she feared for her life—the kids were “bangin’ on my door,” she claimed—her fear was not just personal. It was legal infrastructure. She didn’t need proof of aggression—just a subjective fear, written into law. That’s the dangerous pivot: fear becomes justification when law codifies it.

But here’s the counter-image: that mother who said “they’re all mine,” who knew every child’s name, whose kids got ice-cream at dusk. Her world held doors open, not locked. Her tool wasn’t a gun—it was visibility, presence, belonging. The grief of her community wasn’t manufactured—it was built, deliberately.

Pandemic-Era Atomization and the Rising Surveillance State

The timing matters. The children’s play tends toward noisier when parents work nights, when babysitters vanish, when pandemic isolation drives kids outdoors. The neighbors used to know each other. The little league got rain-checks; trusting eyes trained across fences. But lockdowns stretched months, adults retreated into screens, fences became walls, Ring-cams became all-seeing witnesses.

Lorincz was that someone. She called the cops. She filed complaints. She wasn’t just annoyed—she weaponized law enforcement against the neighborhood children. The police didn’t prevent the killing—they documented the demand. The footage reveals officers responding to her complaints yet being bypassed when the fatal shot rang out. She owned the 911 number like a disturb button for the world she didn’t want.

The message: When public life recedes and private fear ascends, policing becomes a substitute for community. The kids didn’t vanish—they were surveilled. The lot across the street didn’t become empty—it became hyper-visible. And the door between anger and murder didn’t open—it was unlocked.

Adultification Bias as a Warrant for Violence

Another subtle engine in the film is adultification bias: the idea that Black children are perceived as older, more culpable, less innocent than white children. In this story, the kids playing outside were described by Lorincz not as children, but as “thugs,” “trespassers,” “professionals in antagonism.” Police officers responded with skepticism, but the law responded with silence. The legal structure tipped toward those who claimed fear.

Scary as a harassment complaint by a white woman can be, scarier still is when the system listens. Because then children’s play is not treated as activity—it is treated as threat. The causal chain morphs: skateboards, trespass sign, phone, fear, gun. The Hawksley church bells of prejudice start, and by the time the bullet lands, there’s precedent.

By normalizing childish complaint as lethal threat, Lorincz (and the law) reclaimed the neighborhood for herself—and expelled all others. What the documentary reveals is an ascending hierarchy of suspicion: you play, you’re visible; someone complains, cops respond; someone plays back; you die. The excuse: fear. The structure: law. The outcome: death.

The Counter-Culture of Care

But in the shadow of that killing one also sees community care. Gandbhir shows footage of neighbors sitting in carports, handing out food, watching each other’s children, the kind of arrangement we’re told doesn’t exist anymore. The camera sees mothers ready to pick up the slack, fathers coaching. When one woman said “they’re all mine,” it wasn’t metaphor—it was fact.

That network of belonging is what the violent doctrine attacked—but it also shows the alternative. Shared investment in the block, the lot, the road. Mutual child care, not solitude. Public goods, not privatized fear. The film uses everyday scenes to show a living civic life: sidewalk football, high-fives, trust without gates. Then it shows how that trust died.

Because you can’t weaponize fear without killing trust. And once trust dies, the commons evaporates. The kids who owned the block became the strangers someone feared. The lots where they played became the reason for lockdown. The space between fences became the firing line.

The Civic Lesson References Everything

The so-what of The Perfect Neighbor is simple—painful, urgent. Civic institutions save lives. Public science, peer review, shared commitment to care—they expand vision. Privatized fear, racial paranoia, performative police calls—they steal it.

If we fund and protect clinics, journals, parks, playgrounds, we foster place and connection. If we leave open fields but cover them with cameras, we cultivate solitude and suspicion. If law protects only the fearful and arms them with doctrine, we legitimate the defilement of community.

Owens’s killing didn’t happen in a vacuum. It happened where a mother knocked on a door and met gunfire. It happened where the promise of American neighborhood collapsed into cisterns of fear. It happened not because the law mandated murder—but because it permitted it.

And the larger stroke: this is not just Florida. This is suburbs everywhere. The thresholds shift, the triggers normalize, the system rewrites vulnerability as threat. The kids skip, the neighbor watches, the law listens—and the measurement of life changes.

The Dual-Narrative of Belonging and Breakdown

The Perfect Neighbor gives two stories, simultaneous and oppositional: one of cohesion and care, the other of isolated fear and lethal escalation. The neighborhood watched out for each other; it was a living public terrain. Opposite it was a self-styled guardian, storefront of grievance, police hotline for her illusions. One is urgent and alive; the other is frozen and dead.

What’s at stake is that the rich story of belonging matters more than the headline of killing. If you only see the murder you might chalk it up to mental illness, bad law, tragedy. But if you see the common ground being erased you see what’s already gone—public life drained, solidarity stripped. And that’s harder to reverse.

If we let the doctrine of fear win, then we not only lose a mother, we lose a block, we lose a culture of children playing out front, we lose the moment when we said “they’re all mine.” The next time the door bangs and the phone dings we must ask: are we trying to listen or are we trying to shoot?

The Haunting Reflection

When the drones finish their loops and the body-cam footage fades, the question remains: which side of the neighborhood are you on? Are you playing in the lot or calling the cops? Are you trusted or feared? The choice is neither moral nor optional—it’s foundational.

A policy that tells someone “you need not retreat” is more than law—it’s a philosophy of isolation. A community that says “they’re all mine” is more than family—it’s a radical alternative to fear. One magnifies separation; the other repairs connection. One kills while pretending to protect; the other protects by making life better.

The Perfect Neighbor demands not just reflection—but participation. It’s not enough to watch the footage. The film invites us to be the mother who holds all the kids, the architect of the lot where they play, the neighbor who says “I belong”—not the vigilante who says “they don’t.”

Because once we treat private fear as public law, once we hand people the hotline like a cross-bow, we don’t protect the vulnerable—we define them. If we ever confuse common goods with common threats, we’ll wake up in a world where suspicion is default, play is policing, and the phrase “They’re all mine” becomes the exception—not the normal.

And when that happens, the murder behind the locked door is not the tragedy—it’s the symptom.