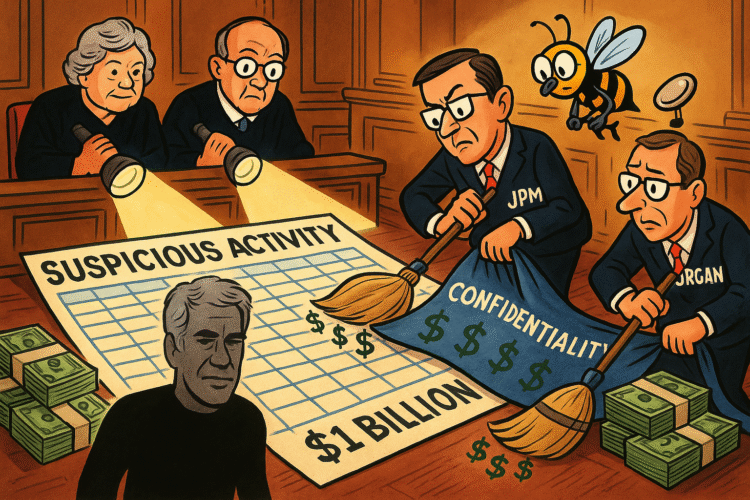

The modern banking system has a curious definition of morality. If you or I move a suspicious thousand dollars, the government freezes our account, our credit dies, and an algorithm red-flags us into financial purgatory. But if you’re Jeffrey Epstein, you can move a billion dollars through the world’s largest bank for sixteen years and nobody blinks—until you’re dead, at which point the paperwork suddenly finds religion.

That’s the story unsealed this week in federal court: a sprawling record of 4,700 transactions across two decades, quietly labeled “suspicious” by JPMorgan Chase only after Epstein’s death in 2019. The total: over one billion dollars in activity, spread through a network of associates, Russian banks, shell entities, and the kinds of names that make compliance officers sweat—Leon Black, Glenn Dubin, and a handful of other polite billionaires who somehow never lose their bank accounts.

The filings confirm what cynics already knew: the financial system doesn’t just enable crime; it monetizes it.

The Bank That Loved Too Wisely and Too Long

The timeline reads like a thriller written by a bored accountant.

- 2002: JPMorgan’s internal emails first flag “reputational risk” around Epstein, then a high-net-worth client with a taste for underage “massage therapists.” Compliance staff suggest monitoring his accounts more closely.

- 2005: Florida prosecutors open investigations into Epstein’s sexual abuse of minors. JPMorgan’s risk team notes concern but keeps the accounts open because Epstein “brings in lucrative business.”

- 2008: Epstein pleads guilty to solicitation of a minor. Most clients would be ejected from a bank at this point. JPMorgan’s solution? Downgrade his “relationship tier” but maintain it.

- 2011: Internal correspondence circulates referencing “continued reputational risk” and “sensitivity given high-profile associations.” The risk committee kicks the can.

- 2013: The bank finally “exits” Epstein as a client—after eleven years of internal anxiety and over a billion dollars in throughput.

- 2019: Epstein is arrested and later dies in custody. JPMorgan belatedly files a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), covering 16 years of transactions that had already passed through its wires.

- 2020-2023: News outlets including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal fight to unseal the SAR-related filings as part of civil litigation involving Epstein’s survivors. JPMorgan claims confidentiality under the Bank Secrecy Act, which prohibits disclosure of SARs.

- This week: Federal judges release redacted portions showing just how deep the transactions ran—and how little anyone did to stop them.

It took Epstein’s death for his banker to discover his crimes.

SARs, Secrets, and the Fine Print of Looking Concerned

For the uninitiated, the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires banks to file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) whenever they detect possible money laundering, fraud, or other crimes. These reports are confidential by law; they’re meant to alert regulators, not serve as public evidence.

In theory, this secrecy protects investigations. In practice, it protects reputations.

JPMorgan’s lawyers fought tooth and nail to keep these filings sealed, citing “confidential supervisory material.” But judges ruled that the public interest outweighed the confidentiality claim, given the scale and pattern of the transactions and the fact that Epstein was, at that point, deceased and no longer entitled to privacy.

What emerged from the unsealing wasn’t gossip—it was a postmortem autopsy of a financial body. The filings describe wire transfers to and from Russian banks, foreign affiliates, and “entities with high-risk typologies” that compliance officers flagged repeatedly. They mention “human trafficking indicators” and “structuring behaviors designed to evade thresholds.”

Translated: Epstein’s money was waving every red flag in the compliance textbook while JPMorgan politely looked away.

Compliance as Performance Art

There’s a darkly comic rhythm to the internal correspondence. Emails show risk officers voicing discomfort while senior executives weigh “business value.” One memo from 2007 references “the client’s social capital and proximity to U.S. presidents,” which, in corporate English, means “he knows people who can make our stock price go up.”

The same memo calls for “enhanced due diligence,” but then immediately cites “relationship sensitivity.” That’s the bureaucratic equivalent of saying, we know he’s dirty, but he’s good for dinner invitations.

By 2011, one compliance executive wrote that “continuing this relationship could prove embarrassing.” They weren’t wrong. It just took eight more years and a death in federal custody for the embarrassment to catch up.

The Cost of Silence

The filings don’t show a rogue banker gone wild; they show an institution structured to prioritize profit over prudence. The “client experience” team worried about hurting Epstein’s feelings. The “relationship managers” viewed compliance as customer service.

And through it all, the system worked exactly as designed.

Epstein remained a “Tier 1” private banking client long after his criminal conviction. His transactions included payments to individuals with non-descriptive memos, wires to offshore accounts, and round-dollar transfers consistent with cash structuring. Any one of those would flag a normal person’s account for immediate review.

For Epstein, they triggered emails like “monitor, but do not escalate unless necessary.”

This is what systemic corruption looks like—not a smoky backroom, but a conference call with PowerPoint slides titled “Reputation Management Strategy.”

After Death, a Paper Trail

When Epstein died in August 2019, JPMorgan’s compliance division sprang into action like a detective arriving after the suspect’s funeral. The bank filed a massive SAR covering all 4,700 transactions across 16 years, citing “posthumous risk review.”

If irony could be patented, that phrase would qualify.

The report totaled over a billion dollars in flagged activity. It traced funds through trusts, shell companies, and personal accounts linked to Epstein’s associates and possible recruiters. Some went through Russian institutions already on FinCEN’s radar. Others cycled through U.S. wealth managers who are now, coincidentally, unavailable for comment.

Among the more eyebrow-raising details: multiple wires tied to Leon Black, the Apollo Global Management founder who later admitted paying Epstein tens of millions for “tax and estate advice,” and Glenn Dubin, the hedge fund magnate whose family maintained social ties with Epstein even after his 2008 conviction.

JPMorgan now insists that filing the SAR proves the system worked. It’s a bit like saying you installed a smoke detector while watching the house burn.

The Legal Theater

The courts have now forced partial transparency in a system built to hide behind statutes. The Bank Secrecy Act forbids banks from confirming or denying SARs. The FinCEN database exists in a sealed world where suspicious activity is acknowledged only in theory.

But the lawsuits surrounding Epstein’s victims changed the equation. Civil plaintiffs argued that JPMorgan enabled trafficking by continuing to bank Epstein despite red flags. The bank settled with the Virgin Islands for $75 million, while Deutsche Bank paid $150 million in regulatory penalties for similar behavior.

Still, neither settlement required the full public release of SARs—until now.

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal intervened in court, arguing that redacted versions were essential for accountability. JPMorgan claimed this would “chill cooperation” with regulators. The judges disagreed, noting that “the public has a compelling interest in understanding the role of financial institutions in systemic criminality.”

That’s polite legalese for: the public deserves to know who got paid to ignore a predator.

The Reputational Fallout

Survivors’ advocates say these revelations prove what they’ve long alleged: Epstein’s power wasn’t mystical. It was transactional. His network functioned because it was profitable.

Bank defenders now insist the SARs prove the compliance system worked “as designed.” Which, if true, is a damning admission. A system that waits until after death to notice a billion dollars of red flags isn’t broken—it’s perfectly calibrated for plausible deniability.

Regulators are weighing whether to issue consent orders or further penalties. FinCEN may demand an “enhanced monitoring agreement.” Translation: a sternly worded letter and a compliance seminar in a hotel ballroom.

But reputational damage has its own gravity. Risk committees at major banks are now fielding uncomfortable questions: How long do we wait before we call a predator a liability? How much profit justifies moral blindness?

There are no formulas for that. Only spreadsheets.

The Broader Lesson

JPMorgan’s defenders love to remind us that the bank “cut ties” in 2013. They omit the part where Epstein continued moving money through other institutions, many of which shared executives or correspondent accounts with JPMorgan. The financial web is small, and money never really leaves the system—it just changes custodians.

That’s why these unsealed documents matter. They reveal not just a client relationship gone bad, but an entire architecture of accommodation. Epstein’s behavior was an open secret in elite circles. So was his bank balance. Both were treated as features, not bugs.

When compliance officers waved red flags, they weren’t ignored—they were absorbed. Each concern became another data point in a cost-benefit analysis where the cost was reputational risk and the benefit was revenue.

That calculus didn’t end with Epstein. It’s how modern finance works.

The Real Crime Scene

Strip away the legal jargon and the filings tell a simple story: the spreadsheet is the crime scene. Every cell, every transaction ID, every memo marked “monitor” instead of “report” is a witness statement.

The numbers reveal how crime hides in plain sight, cloaked in wire codes and compliance euphemisms. It’s not a conspiracy—it’s a procedure.

When you look closely, the most damning thing isn’t that JPMorgan enabled Epstein. It’s that the bank didn’t have to break any laws to do it.

Consequences Pending, Accountability Deferred

In the coming weeks, regulators will decide whether to pursue additional penalties. Congressional committees may summon executives to testify. State attorneys general could issue subpoenas to trace the Russian bank pathways.

Names like Leon Black and Glenn Dubin will surface again, each accompanied by statements denying wrongdoing while expressing “deep regret.” The news cycle will move on. The survivors will not.

The rest of us will be left with a question: how many zeroes does it take to erase morality?

Because at the heart of this story isn’t a billionaire pervert or a negligent banker—it’s a system that prices ethics the same way it prices assets, in basis points and brand risk.

Closing Section: The Price of Looking Away

When history writes the chapter on Epstein and his bankers, it won’t be about one man’s crimes. It will be about the institutions that found profit in proximity.

The unsealed filings show that modern finance has become fluent in the language of plausible ignorance. Every red flag becomes a revenue stream until it becomes a headline. And even then, the system survives.

In court, a JPMorgan attorney reportedly argued that “no compliance system can foresee every eventuality.” Maybe not. But they can certainly stop pretending blindness is foresight.

This week, the veil lifted on how billion-dollar crime flows coexist with cocktail parties and quarterly earnings calls. The story isn’t shocking. It’s familiar. That’s the tragedy.

Because in the end, it took death, litigation, and a judge’s order just to confirm what everyone already knew: the money always finds its way, and the gatekeepers always find a reason to let it through.

If there’s justice left in the balance sheets, it will come not from regulators or shareholders, but from the slow erosion of public trust in institutions that treat legality as morality.

The spreadsheet doesn’t lie. It’s just waiting for someone to read it out loud.