The algorithm finally bought the dream factory, and it paid cash.

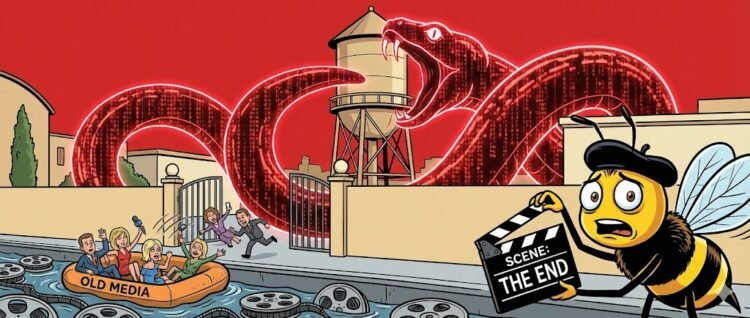

It is finished. The war for the soul of Hollywood, a conflict that has raged since the first DVD was mailed in a red envelope, has ended not with a treaty but with an unconditional surrender. In early December 2025, the unthinkable became the inevitable. Netflix, the company that taught us to binge-watch mediocre reality television until our eyes bled, has prevailed in its blockbuster bid for Warner Bros. Discovery’s studios and streaming assets. The deal, valued by sources at a staggering $72 billion to $83 billion, is the financial equivalent of a asteroid impact. It obliterates the landscape we knew and replaces it with a crater shaped like the letter N.

The specifics of the transaction are a masterclass in late-stage capitalist brutality. Netflix put an offer on the table priced around $27.75 per WBD share in a mix of cash and stock. This was, notably, less than the flashy $30 a share offer dangled by rival suitor Paramount Skydance. But in a town that runs on credit and bluffing, cash is still king. The Skydance bid, backed by the deep pockets of the Ellison family, reportedly withered under the heat of financing doubts. Warner Bros. looked at the promise of tech-bro money versus the reality of Netflix’s subscriber base and chose the monster they knew.

But the devil is in the details, or rather, in the carve-outs. This isn’t a clean acquisition. It is an amputation. To make the numbers work and perhaps to dodge the immediate wrath of regulators, the transaction has been narrowly carved to exclude the linear cable assets. This means that CNN, TNT, TBS, HGTV, and the rest of the cable bundle’s greatest hits will be spun out into a new public company called “Discovery Global” in mid-2026.

Let’s be clear about what this means. Netflix is taking the diamonds and leaving the coal. They are taking HBO. They are taking the Warner Bros. studio lot. They are taking DC Comics and the vast libraries of film and television history. They are taking the things that people actually want to watch. And they are leaving the dying carcass of cable television to rot on an ice floe, presuming that a standalone company consisting of Wolf Blitzer and House Hunters reruns has a viable future in the streaming age. It is the corporate equivalent of looting the mansion and leaving the deed to the gardener.

The Algorithm Inherits the Earth

The cultural implications of this merger are enough to make a cinephile weep into their popcorn. Warner Bros. is not just a studio. It is the studio. It is the shield that heralded Casablanca, The Matrix, and The Sopranos. It represents a century of artistic risk and directorial vision. Netflix, conversely, represents the triumph of “content” over “art.” Netflix is the house that built Is It Cake? and spent billions on movies that look like they were lit by a fluorescent bulb in a hospital hallway.

Now, these two cultures are being mashed together. We are witnessing the forced marriage of the auteur and the algorithm. The fear, palpable in every writers’ room and guild hall in Los Angeles, is that the Warner Bros. legacy will be flattened to fit the Netflix interface. Will HBO remain the gold standard of prestige television, or will it simply become a “vertical” in the Netflix app, sandwiched between Bridgerton and a documentary about a serial killer you’ve never heard of?

The deal structure leaves Netflix with an arsenal of IP that borders on the monopolistic. They now own Superman. They own Harry Potter. They own Game of Thrones. They have effectively cornered the market on cultural nostalgia. And they did it by assuming a massive debt load and a $5.8 billion breakup fee, a number that suggests they are so confident in their dominance that they are willing to bet the farm on it.

The Antitrust Theater

Naturally, Washington has woken up from its nap to express concern. Lawmakers like Representative Darrell Issa and Senator Mike Lee are issuing vocal warnings, dusting off the Clayton Act and other competition statutes that usually sit on the shelf next to the ethics manuals. They are threatening hearings. They are talking about market concentration.

But let’s be honest about the efficacy of modern antitrust enforcement. It is theater. The Department of Justice and the FTC will review the deal. There will be stern letters. There will be grandstanding speeches about the danger of consolidation. But the history of the last forty years suggests that when a check this big is written, the government usually finds a way to cash it politically.

The argument Netflix will make is simple and seductive. They will argue that they are not a monopoly because they are competing with Amazon, Apple, and Google. They will define the market so broadly—”attention”—that buying a major movie studio looks like a minor transaction. They will issue public statements, as their executives already have, defending the scale as necessary to compete with Big Tech. They will talk about “subscriber value” and “preserving jobs,” the twin shields of every corporate raider.

The irony is that the “concerned feature film producers” who anonymously begged Congress to stop this are right. This deal threatens the very existence of the theatrical window. Netflix has always viewed movie theaters as an inefficiency, a friction point that prevents you from staying on their platform. With Warner Bros. under their control, the pressure to shrink theatrical runs to zero will be immense. Why let The Batman play in theaters for three months when it could drive Q3 subscription growth?

The Skydance Bullet Dodged (Or Was It?)

We must pause to consider the alternative. The counterfactual where Paramount Skydance won the bid is a fascinating “what if” scenario. Backed by David and Larry Ellison, that bid promised a different kind of nightmare. There were legitimate fears among CNN staff that an Ellison-backed ownership group would threaten newsroom independence, turning the network into a vanity project for tech oligarchs.

So, in a grim way, the Netflix deal is the “safe” option for the journalists at CNN, simply because Netflix doesn’t want them. By being spun off into Discovery Global, CNN avoids the Ellison influence, but it also loses the safety net of a massive corporate parent. It is being cast out into the wilderness of independent media, forced to survive on its own revenues in a dying cable market. It is a reprieve that looks a lot like a slow execution.

The Skydance bid was $30 a share. That is a significant premium over the Netflix offer. The fact that the WBD board chose the lower price tells you everything you need to know about the fragility of the financing. They looked at the Ellison money and saw risk. They looked at the Netflix stock and saw liquidity. In the end, they sold the legacy of the studio for the certainty of the payout.

The Human Cost of “Synergy”

The press releases speak of “synergy” and “optimization.” In English, that means layoffs. The overlap between Netflix and Warner Bros. is significant. You don’t need two marketing departments. You don’t need two legal teams. You don’t need two distribution arms.

The guilds are alarmed for a reason. This consolidation erodes their bargaining power. When there are only three buyers left in town, labor loses its leverage. If you are a writer or an actor, you can’t play Netflix against Warner Bros. anymore because they are the same person. You take their offer, or you go make a TikTok.

Theater owners are staring into the abyss. Warner Bros. was one of the few studios committed to the theatrical experience. They believed in the magic of the cinema. Netflix believes in the magic of the couch. If Netflix decides to starve the theaters of Warner Bros. content, or release it day-and-date on streaming, the entire business model of the exhibition industry collapses. The popcorn is stale, and the lights are flickering.

The Spin-Off to Nowhere

Let’s return to “Discovery Global,” the new company that will house the cable assets. It is a concept that feels like a bad joke. Who invests in a standalone cable company in 2026? It is a “bad bank” for media assets, a place to park the declining businesses so they don’t drag down the stock price of the streaming giant.

Mid-2026 is the target date for the spin-off. Until then, these channels exist in a zombie state, waiting to be exiled. It is a humiliating end for brands like CNN and TNT, which once dominated the cultural conversation. Now, they are the unwanted leftovers of a meal Netflix didn’t want to finish.

This structure allows Netflix to claim they aren’t a monopoly in news or sports (mostly), while securing total dominance in entertainment. It is a surgical carving of the carcass, designed to bypass the Clayton Act by shedding the parts that attract political heat.

The Future of the Mid-Budget Movie

The biggest casualty of this deal will likely be the mid-budget movie. Warner Bros. was one of the last places you could make a movie for $60 million that wasn’t a superhero franchise. They made dramas. They made comedies. They made movies for adults.

Netflix’s algorithm hates the mid-budget movie. It loves the cheap reality show and the massive blockbuster. The middle is the kill zone. Under the Netflix regime, the nuanced, character-driven drama that Warner Bros. used to champion will be replaced by content designed to be played in the background while you fold laundry.

This is the “downstream consequence” for consumers. We will get more content, but less art. We will get more hours of television, but fewer moments of brilliance. The diversity of the marketplace will shrink to a single red icon on your home screen.

Conclusion: The End of the Studio Era

The acquisition of Warner Bros. by Netflix marks the official end of the studio era. The power has shifted irrevocably from the people who make movies to the people who distribute them. The pipe is now more important than the water.

We are entering a monoculture. A world where a single company controls the vast majority of our cultural heritage. They own the past (the libraries), they own the present (the production studios), and they own the future (the distribution platform).

It is a terrifying amount of power to hand to a company that treats creative decisions like A/B testing. We are about to find out what happens when the logic of Silicon Valley is applied to the soul of Hollywood.

The “Red N” has swallowed the shield. The water tower in Burbank might as well be repainted tomorrow. The history of Warner Bros. is now just metadata in the Netflix search bar.

The courts may weigh in. Congress may hold hearings. But the momentum is undeniable. The check has cleared. The deal is done. And somewhere in a server room in Los Gatos, an algorithm is already deciding which classic Warner Bros. movie to reboot as a reality competition series.

Receipt Time

The invoice for this cultural acquisition is in the billions, but the real cost is incalculable. We are paying for this consolidation with the loss of variety, the erosion of labor power, and the death of the theatrical experience. The receipt shows a credit for “Efficiency” and a debit for “Soul.” The $5.8 billion breakup fee is a rounding error compared to the value of the history that has just been sold for parts. We are all subscribers now, renting our culture from a landlord who raises the rent every year and cancels our favorite shows without explanation. The transaction is complete, and we are left holding the remote, scrolling endlessly through a library we no longer recognize.