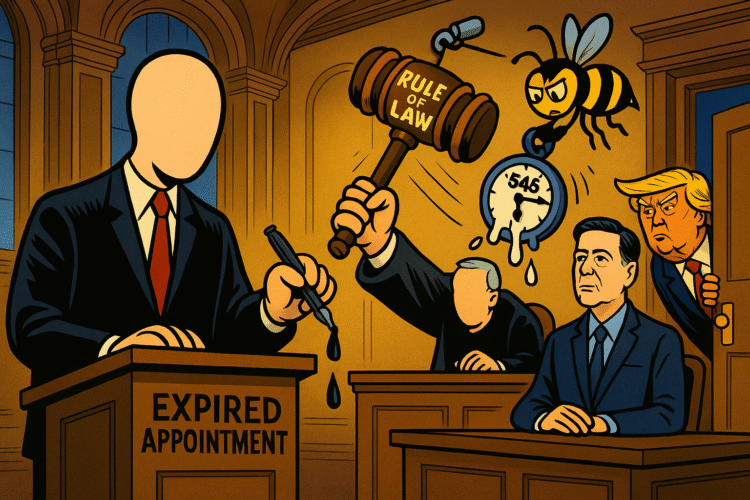

At some point, the Department of Justice stopped pretending to be about justice and started acting like a casting call for vengeance. This week, a federal judge finally noticed. In the Trump Justice Department’s long-running revenge play against former FBI Director James Comey, the court pressed pause—not on the facts, not on the charges, but on something more fundamental: whether the prosecutor who signed the indictment even had the legal right to do so.

The question isn’t procedural nitpicking. It’s existential. Because if the lead prosecutor was unlawfully installed, then the case isn’t just tainted—it’s radioactive. Every motion, every signature, every subpoena becomes the bureaucratic equivalent of a forged check.

Act I: The Man With the Vanishing Mandate

At the center of this legal fever dream is a man whose title is longer than his tenure: Acting U.S. Attorney Daniel R. Hastings, appointed sometime last spring after the prior officeholder quietly “resigned” under the kind of duress only a political purge can provide. The Justice Department insists Hastings was properly appointed under 28 U.S.C. § 546, which governs how interim U.S. attorneys are installed. The defense argues that’s a fantasy.

Under § 546, the Attorney General can appoint an interim U.S. attorney for 120 days. After that, the district court must either reappoint or the post sits vacant until a Senate-confirmed replacement arrives. Simple statute, clear timeline. Except in this case, the clock ran out months ago. The Trump administration, rather than seeking confirmation or reappointment, simply pretended the clock didn’t exist. Hastings kept signing filings as though deadlines were an emotional suggestion.

Comey’s defense counsel, led by veteran litigator Susan Feigenbaum, called it what it is: an appointments landmine. “The Constitution doesn’t allow phantom prosecutors,” she told the court. “If the executive branch can manufacture authority out of thin air, then separation of powers is dead by paperwork.”

Act II: The Chain of Command, or How to Build a Scandal

According to internal memos pried loose by discovery, the chain of command looks like a civics exam gone wrong. The deputy attorney general signed a memo designating Hastings “for continuity of operations.” The memo cited “urgent national interest,” a phrase that apparently now means “we couldn’t be bothered to nominate anyone.” The Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) reviewed it two weeks later, raised red flags about exceeding statutory limits, and was promptly ignored.

By mid-summer, internal DOJ emails showed career lawyers privately joking that “546 has left the chat.” Meanwhile, the White House counsel’s office received a briefing summarizing “appointment continuity options.” That briefing, dated June 14, bore the initials of two senior staffers later linked to efforts to replace independent prosecutors with “loyal interims.”

When Hastings finally signed the indictment against Comey in late August, he did so more than 200 days after his interim clock had expired. The filing bore the seal of an office that technically didn’t exist.

It’s not just bad optics—it’s illegal.

Act III: The Docket That Ate the Rule of Law

The case itself, United States v. Comey, has been marinating in procedural dysfunction since day one. The charges—obstruction and unauthorized disclosure tied to post-FBI memos—were always thin gruel. But the procedural implosion gives new meaning to “fruit of the poisonous tree.”

At the hearing this morning, Judge Marianne Caldwell looked visibly unimpressed. “If the prosecutor wasn’t lawfully appointed,” she said, “what exactly are we doing here?”

The government tried to salvage dignity. “Your Honor,” argued lead counsel Mark Lunsford, “any defect in the appointment is harmless error.” Caldwell blinked. “Harmless?” she asked. “You’re suggesting an unlawful officer can prosecute citizens and it’s…harmless?” The gallery erupted in laughter.

The courtroom shorthand for this moment is “bad day for the government.”

Act IV: Appointments Clause, Meet Karma

The defense motion draws a clean constitutional line. The Appointments Clause in Article II of the Constitution requires principal officers—like U.S. attorneys—to be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Congress carved a narrow exception under § 546 for temporary service, but only for a defined time. When that time runs out, so does the power.

As Feigenbaum put it: “The Framers didn’t design expiration dates for yogurt but not for prosecutors.”

The Trump administration, however, treated appointments like favors at a fundraiser. Hastings, like several other interim appointees across the country, was installed during a wave of retaliatory replacements. Federal judges in Maryland and Texas have already ruled similar appointments unlawful, invalidating everything from plea deals to warrants. Now, with the Comey case, the legal infection has reached the brainstem.

If the court finds Hastings unlawfully appointed, it won’t just invalidate the indictment—it could blow a hole in every action taken by his office since spring. Subpoenas, filings, even settlement agreements could unravel like loose thread on a counterfeit flag.

Act V: The Ghosts of DOJ Past

Former DOJ leaders are watching with alarm. “You can’t defend the rule of law with illegal prosecutors,” said former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates in an interview. “If appointments become political weapons, justice becomes performance.”

Even some conservatives admit the optics are grotesque. “This is the legal equivalent of driving without a license,” said one former U.S. attorney who spoke on background. “You can get away with it until someone asks to see the paperwork.”

The White House, predictably, insists “the paperwork is fine.” Asked for comment, a spokesperson said the appointment “followed standard procedure,” though when pressed, could not produce a single document showing who reappointed Hastings after the statutory window closed. The exchange ended with the press secretary declaring the matter “fake legal news,” which, in fairness, is the administration’s answer to gravity.

Act VI: The Leaky Vessel Called Justice

Inside the Department, morale is subterranean. Line attorneys have begun referring to the case as “Comey’s Comet”—bright, brief, and destined to crash. Some whisper about retaliatory purges that installed loyalists willing to file politically motivated charges. “The message was clear,” said one career attorney. “Play ball or be reassigned to immigration court in Amarillo.”

Others describe the eerie quiet following Judge Caldwell’s questions. “It was like someone opened a door and the air changed,” one observer said. “For the first time, the bench asked if any of this still counts as law.”

The irony is that the Comey prosecution, billed as proof of accountability, may now become the showcase of corruption.

Act VII: The Timeline of Self-Inflicted Wounds

The sequence of events reads like a parody of governance:

- March: Original U.S. attorney resigns under pressure.

- April: Daniel Hastings installed under § 546(b) as “interim.”

- June: 120-day statutory window expires. No nomination, no court reappointment.

- July: DOJ’s internal audit flags “status irregularities.” Ignored.

- August: Hastings signs indictment against Comey.

- September: Defense files motion to dismiss based on unlawful appointment.

- October: DOJ argues “de facto authority doctrine” shields actions.

- November: Judge Caldwell orders full hearing on Appointments Clause compliance.

Each step builds toward the same absurdity: a government too consumed by vengeance to notice it tripped over its own constitution.

Act VIII: The Doctrine of De Facto Desperation

The government’s fallback is the “de facto officer doctrine,” an old legal relic that lets courts uphold actions by officials later found unlawfully appointed—so long as no one objected in time. It’s the administrative equivalent of “we meant well.”

Feigenbaum’s response was surgical: “The doctrine protects the innocent, not the incompetent.” She argued that the Comey team raised the issue immediately and that Hastings’ tenure wasn’t a technical glitch but a deliberate end run around the Senate.

Judge Caldwell seemed inclined to agree. “This isn’t a clerical mistake,” she said. “It’s a structural one.”

If she rules against the government, the Justice Department faces a nightmare: re-presenting the case to a grand jury under a properly confirmed U.S. attorney, if one even exists.

Act IX: The Separation of Powers on Life Support

Beyond the legal theater lies a constitutional crisis disguised as paperwork. The Appointments Clause exists to prevent precisely this—political actors seizing prosecutorial power without oversight. But under Trump’s DOJ, the clause became optional fine print.

The Comey case now functions as a civics Rorschach test. If you see accountability, you’re blind. If you see politics, you’re awake.

The question Judge Caldwell asked—“Does the Appointments Clause still mean anything?”—should haunt every lawyer in the room. Because if the answer is no, then the next administration, and the one after that, will have precedent to install loyalists by memo, prosecute opponents by whim, and call it continuity.

This isn’t just about James Comey. It’s about whether the Constitution still fits inside the Department of Justice.

Act X: The Reactions and Rationalizations

Cable news turned the hearing into a circus. Conservative pundits called the defense “desperate lawyering.” Progressives called it “karma with footnotes.” Legal Twitter exploded with memes of ghost prosecutors holding expired calendars.

Former DOJ officials tried to be dignified. “This is not about personalities,” said one retired career attorney. “It’s about process.” Then he sighed. “But yes, it’s also about personalities.”

At the White House, officials dismissed the controversy as “judicial activism.” One aide reportedly told a reporter, “You think the voters care who signed the paper?” The problem is, the voters might not—but the courts do.

Act XI: The Domino Effect

If the Comey indictment collapses, it won’t be the only casualty. Other Trump-era prosecutions involving similarly expired interim appointments are already being quietly reassessed. Internal memos reviewed by oversight staff show that at least five districts may have exceeded their 120-day windows.

That means dozens of cases could be tainted. Plea agreements, search warrants, asset seizures—all at risk. It’s the bureaucratic version of a nuclear meltdown: one bad appointment contaminating everything downstream.

Congressional Democrats are preparing oversight hearings. Inspectors general are drafting subpoenas for internal emails. The word “weaponization” has migrated from political rhetoric to literal evidence tags.

Act XII: The Near-Term Checkpoints

Here’s what happens next:

- Evidentiary Hearing: Judge Caldwell is expected to order testimony from DOJ’s appointments officer, the deputy attorney general, and possibly Hastings himself. The focus: who knew the clock had expired, and when.

- Compliance Audit: The OLC will likely issue a belated memo clarifying that 28 U.S.C. § 546 still means what it says. Expect bureaucratic throat-clearing about “process improvements.”

- Grand Jury Do-Over: If the indictment is tossed, DOJ may try to re-present the case under a lawfully appointed U.S. attorney. That would require starting from scratch, a symbolic concession of defeat.

- Congressional Oversight: Lawmakers will demand the emails showing how “continuity memos” became end runs around confirmation.

- Media Reckoning: Will any major outlet have the spine to say it plainly—that an unlawful prosecutor makes the prosecution itself unlawful? Or will they call it “unusual procedural turbulence” and move on?

Coda for a Government of Ghosts

In a republic held together by paper, the signatures matter. And when the signature itself is illegal, the law dissolves into theater. The Trump DOJ’s vendetta against James Comey began as payback and may end as parody.

If the prosecutor wasn’t lawfully in office, then this isn’t a case—it’s a confession. The government has indicted itself for contempt of its own Constitution.

The irony is almost poetic. The same administration that promised to “drain the swamp” now finds its justice department clogged with its own muck. The Constitution isn’t a suggestion, and the Senate isn’t a prop. You can’t appoint your revenge by memo and call it rule of law.

When history writes this chapter, it won’t remember the docket number or the filings. It will remember the question that cut through the noise: what happens when the prosecutor is the crime?

Because if the enforcer isn’t lawful, then the law itself becomes the punchline.