Indiana discovers that if you squint hard enough, teaching racism is now suppressing intellectual diversity.

The modern university used to worry about things like research output, crumbling lecture halls, and whether students would riot if the dining hall replaced curly fries with the straight, morally ambiguous kind. Indiana University Bloomington has discovered a more avant garde dilemma. It begins with a perfectly ordinary graduate social work course titled “Diversity, Human Rights and Social Justice” and ends with a professor suspended from it for doing the thing she was, on paper, literally hired to do. The spark was a graphic known as the “pyramid of white supremacy,” a teaching tool that has floated around antiracist circles for years. Within weeks, that pyramid had turned into a guillotine for Jessica Adams, the lecturer who dared to use it in class, and a new test case for how enthusiastically lawmakers can use oversight statutes to turn college teaching into a gladiator pit for ideology.

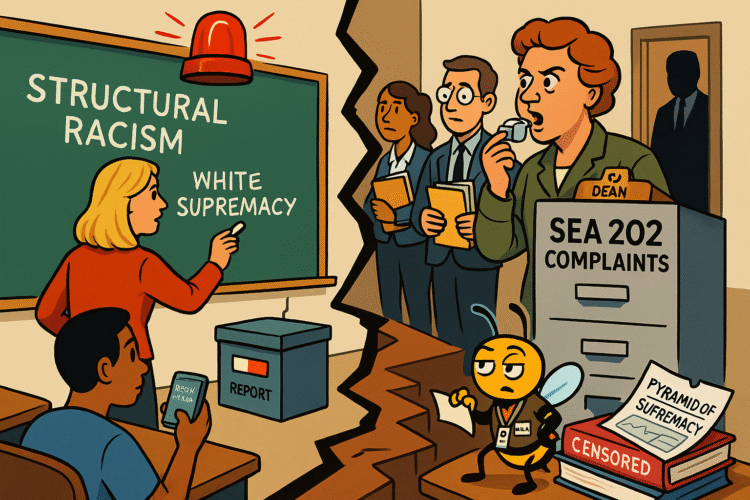

Adams did not stumble into this assignment by accident. Indiana University hired her specifically to teach structural racism in the School of Social Work, presumably aware that structural racism is not a delicate watercolor hobby. It requires naming the thing. Not hinting. Not murmuring. Naming it. Her course included the Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence’s pyramid graphic that sorts racist behaviors on a spectrum from socially sanitized at the bottom to overtly violent at the top. The lower rungs include things like the “Make America Great Again” slogan and Columbus Day, which some students interpret as gateways, not equivalencies, to the more brutal acts near the top hierarchy. In most classrooms this would be debated, side eyed, interrogated, maybe even loudly critiqued. In this classroom it became grounds for a political tribunal.

One of Adams’s master’s students complained that by using the graphic she had equated MAGA with lynching and police killings. Another student in the same room contradicted that claim and said no such equivalence was made. In a functioning university, the next step would involve office hours, awkward conversations, extra readings, perhaps a pointed reminder that graduate school is not a spa for immaculate ideological comfort. Instead, the complaint took a field trip. The student sent it to the office of Republican senator Jim Banks, an elected official who has never been accused of leaving culture war opportunities on the table. His staff forwarded the complaint to the School of Social Work dean, Kalea Benner. And in the blink of an eye, the dean became the primary complainant, transforming a classroom disagreement into a formal investigation under Indiana’s new Senate Enrolled Act 202.

If the number sounds familiar, that is because SEA 202 is the legislative lovechild of a national movement to treat “intellectual diversity” as an endangered species and to treat professors as its natural predators. The law allows students to report instructors who allegedly suppress intellectual diversity or insert “non germane” political views into coursework. The penalties are not symbolic. They include discipline, demotion, and termination. The phrase “non germane” has already entered the American lexicon as a convenient political sorting mechanism that bears a suspicious resemblance to “things I do not want to hear in class.”

Adams was removed from teaching the course while the investigation proceeds. Her other courses continue as if nothing happened. “Diversity, Human Rights and Social Justice,” however, is being patched together with rotating guest lecturers like a wounded ship held together with rope and inspirational quotes. Students say they have essentially paid for a course without a real instructor, and one, Chelsea Adye Villatoro, described feeling financially trapped. Refunds are not part of the SEA 202 curriculum.

The university has adopted a bland studied silence. IU spokesperson Mark Bode declined to comment, citing a policy against discussing personnel matters, a sentence that has appeared in so many higher education statements it might qualify as an honorary adjunct professor. But the message from the administration is unmistakable. The investigation proceeds, the law is in effect, and faculty are expected to intuit where the invisible tripwires are.

The American Association of University Professors and campus activists have rallied around Adams, arguing that IU is weaponizing SEA 202 to chill antiracist pedagogy. In plain English, if you teach about white supremacy too forthrightly, you risk being accused of suppressing conservative viewpoints. And if you teach about racism too delicately, you fail your students. It is the kind of lose lose paradox that would make a lesser philosopher slam their chalkboard and take up carpentry.

Law professor Steve Sanders, who serves as an associate dean at the law school, has issued careful warnings that SEA 202 invites politically motivated complaints and pressures faculty to self censor. This is not alarmism. It is a clinical description of the system in action. A student complaint bypassed ordinary academic channels. A senator’s office became the carrier pigeon. A dean became the primary accuser. The law’s mechanisms clicked into place like a climate controlled Rube Goldberg machine.

The graphic at the center of the storm, the pyramid of white supremacy, is not a new invention. It is also not a mystical talisman. It is a visual tool that maps how social norms, coded language, holidays, slogans, celebrations of colonization, and cultural habits can create conditions that make explicit racism easier to rationalize. Teachers have used it for years to spark discussion. Critics dislike it for a predictable reason. It disrupts the fantasy that racism only exists if accompanied by a hood and a torch. It refuses to let culturally sanitized behaviors wash themselves clean simply because they lack violence.

The complaint against Adams reframed the pyramid as a smear against conservatives, an attempt to paint MAGA as equivalent to murder. Equivalence is not how the graphic works, but equivalence made a better headline. And once the issue was dropped into the bloodstream of partisan politics, the truth did not stand a chance.

SEA 202 functions as a kind of ideological customer service desk. Anyone can file a ticket. The university is obligated to respond. And faculty must now decide whether naming historical and contemporary white supremacy counts as legitimate pedagogy or a “non germane political insertion.” The result is predictable. Silence grows. Lessons shrink. Students learn less. Legislators declare victory.

Meanwhile, the affected students are stuck in a pedagogical purgatory. They are watching the course limp along with guest lecturers who did not build its syllabus and cannot offer long term continuity. Some of them say they do not know how to complete assignments. Others report confusion about grading. They are paying for an instructor they do not have, in a course the university is simultaneously running and not running. It is a Schrödinger’s class.

Adams herself has said she cannot teach structural racism without naming the structures. It would be like teaching marine biology without acknowledging the ocean. But Indiana’s new statutory environment imagines a version of academia where structural racism can be invoked only in hushed euphemisms, where white supremacy is acceptable to discuss if it is a museum artifact but not if it appears in contemporary political analysis. It is an academic world built on the principle that describing reality too accurately becomes political propaganda.

Observers note that the treatment of Adams is unusually punitive compared to other SEA 202 reviews. Usually, complaints lead to consultations or low stakes corrective conversations. Removing an instructor from a course mid semester is a serious intervention. It is the sort of punishment that reveals the law’s real purpose. Not balance. Not diversity of thought. Enforcement. Deterrence. Fear.

This is not unique to Indiana. States across the country have introduced their own versions of classroom surveillance, motivated by a conviction that discussions of race, power, and history are inherently subversive. SEA 202 might now serve as a blueprint. What happens in Bloomington will not stay in Bloomington. Administrators elsewhere will study the mechanics. Legislators will draft copycat bills. Students will learn that the easiest way to control a classroom is to threaten the career of the person standing at the front of it.

The stakes are too obvious to require theatrical embellishment. If teaching about racism exposes faculty to accusations of bias, the next step is simple. Teachers will teach less about racism. And if students learn less about racism, the myth of racial innocence becomes easier to preserve. Education becomes a curated performance of neutrality where uncomfortable truths are scrubbed out for bipartisan palatability. The classroom becomes a stage set where the props are real but the dialogue is censored.

Indiana University now sits in the center of a national experiment. Can a university preserve academic freedom while simultaneously promising the legislature that it will police ideas? Can a professor teach about white supremacy without being accused of suppressing political viewpoints? Can social work education maintain its ethical commitments when political actors stand ready to intervene at the first sign of ideological discomfort? These are not theoretical questions. They are the new operating conditions of public higher education.

Jessica Adams’s case is the kind that produces long term precedents. Not the glamorous kind that end up in casebooks, but the quiet kind that rewires institutional culture. If the investigation ends with a reprimand, faculty will take note. If it ends with discipline, they will take cover. If administrators conclude that the safest way to comply with SEA 202 is to avoid teaching structural racism altogether, students will inherit a curriculum hollowed out for political ease. The pyramid of white supremacy will not disappear. It will simply be banned from the classroom while thriving everywhere else.

The Lesson They Hope You Don’t Learn

In the next stretch, watch how IU handles the investigation behind closed doors. Watch whether the university restores Adams to her course or treats her removal as a cautionary tale for the rest of the faculty. Watch whether lawmakers in other states begin citing Indiana as proof that policing classrooms is both easy and institutionally rewarded. And watch whether the public recognizes the quiet irony taking shape. A professor hired to teach about structural racism is under investigation for naming it. A course meant to examine justice is being held hostage by a law that mistakes discomfort for discrimination. And a university that once claimed to defend intellectual inquiry is now perfecting the art of making truth negotiable.