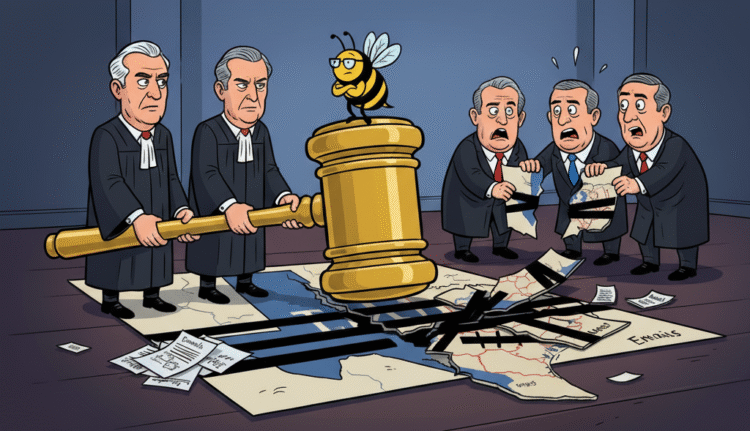

The quiet, un-televised cruelty of American political mechanics often hides in plain sight, tucked away in the arcana of cartography and statute. It is, perhaps, fitting that the quietest, most surgical rebuke to Texas Republican political dominance did not come from a grand moral proclamation or a sweeping popular wave. It came instead from a three-judge federal panel in El Paso, which executed a judicially devastating 2-1 ruling, efficiently nuking the mid-decade congressional map that Governor Greg Abbott had signed into being. The whole affair reads less like sober jurisprudence and more like a detailed receipt for institutional hubris, meticulously itemizing the moment when “partisan hardball” became “sorting voters predominantly based on race.”

This particular cartographic venture, designed and rammed through by the GOP majority, was meant to be the masterstroke for the 2026 midterms and beyond. Its goal was a clean, ambitious prize: squeezing up to five extra Republican House seats out of a state that is rapidly diversifying away from them. To achieve this, the mapmakers had to perform a specific, almost anatomical dissection of the existing electoral body politic, targeting and dismantling the crucial Black and Latino “coalition” districts that had previously offered a meaningful—if tenuous—path for Democratic representation.

What they replaced them with were not competitive districts, but rather carefully engineered, cynical substitutions. These were the so-called “majority Hispanic” seats, where the percentage of Latino voters was numerically high, yet strategically diluted. The lines were drawn with such surgical precision that, despite the demographic makeup, the prevailing turnout patterns and internal voting habits ensured the election of reliable, white conservative Republicans. The mechanism was less about representation and more about highly effective, anti-majoritarian control. The political engineers of the Texas legislature acted with the quiet confidence of people who believed the evidence of their intent could be dismissed as coincidence.

State lawyers, deployed to defend this masterpiece of creative geometry, argued under oath that any suggestion of racial bias was absurd, a fever dream of the opposition. They claimed, with mock seriousness, that this was simply the rough and tumble of partisan hardball, the natural function of one party maximizing its strength against another. The irony was structural: they insisted they were targeting political affiliation, not race, knowing full well that in modern Texas, the two are often functionally inseparable. That thin, legally fraught line is where the entire case pivoted.

The nine to ten days of the actual trial felt like a procedural unearthing of a crime scene. A steady, damning stream of internal evidence was presented to the court. Expert maps showed the dizzying, illogical paths the new district lines took to avoid concentrations of non-white voters. Even more damaging were the internal emails, the digital paper trail of legislative intent. These documents demonstrated, with a clarity the state could not obfuscate, that Abbott himself had explicitly ordered lawmakers to redraw the districts based on the nonwhite racial composition of the populations.

The judges, David Guaderrama and Jeffrey Brown, two jurists whose professional temperaments likely preferred spreadsheets to political theater, were presented with an undeniable pattern. They cited evidence, including a letter from the Trump-era Department of Justice’s own civil rights division, that provided a stark warning to the very legislature it was supposed to be protecting. The evidence was overwhelming, suggesting that the architects of the map had, in a fit of overconfidence, simply left too many receipts lying around.

Their conclusion was therefore rendered with a dry, procedural sting: the state had engaged in “sorting voters predominantly based on race.” It was an indictment delivered not with outrage, but with the flat, careful language of a judicial ruling. It was a finding that cut through the rhetorical haze of “political maximizing” and landed directly on the unconstitutional bedrock of racial discrimination. In a political era defined by the blurring of lines and the relentless gaslighting of objective reality, this clarity felt almost jarringly precise.

The immediate consequence of the panel’s injunction was narrative chaos. The court forced Texas to revert to its previous, 2021 congressional map, effectively blowing up years of careful strategic planning for the Republican machine. For the Republican hopefuls who had already staked their careers, launched their campaigns, and spent their money in the newly gerrymandered districts, the ruling was a sudden, financially ruinous collapse. Their maps were literally erased out from under them.

Simultaneously, the injunction reopened electoral paths for the Democratic incumbents who had been so surgically carved out of their own seats that their careers were thought to be functionally over. The landscape shifted violently overnight, demonstrating that even the most deeply entrenched, seemingly permanent political arrangements are still fragile under the weight of constitutional accountability. It was the swift, chaotic unwinding of a political fantasy.

The reaction to the ruling was a perfect study in contemporary political dissonance. From the civil rights community, organizations like the NAACP and the Legal Defense Fund offered cheers of rare and genuine triumph. In the modern era of conservative judicial dominance, a win of this magnitude against a racially discriminatory map is a procedural anomaly, a moment of profound, if precarious, vindication for decades of tireless legal work. It proved that the courts, for all their skepticism toward partisan claims, still technically recognize the category of racial gerrymandering as a bridge too far.

In Austin, the response from Governor Abbott and the Texas GOP leadership was one of performative, predictable outrage. They immediately denounced the ruling, arguing that any suggestion of racial bias was “absurd,” a claim that was itself absurd given the mountain of evidence the judges had just weighed. They have now begun the inevitable, frantic race to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States. They are banking on the highest court’s current skepticism of all things that touch voting rights.

The irony is that the Supreme Court, in its infinite wisdom, has essentially washed its hands of partisan gerrymandering, deeming it a non-justiciable political question, but it has theoretically kept the ban on racial gerrymandering intact. The Texas Republicans are now appealing to the very judicial body that helped create the legal vacuum in which this kind of legislative overreach could flourish. They are hoping the nine justices are incapable of seeing the difference between targeting voters because they are Democrats and targeting them because they are Black and Latino voters who overwhelmingly vote Democratic.

This distinction is the thin, almost invisible membrane separating a legal act of political self-preservation from a federal constitutional violation. It is a distinction that national strategists, both Republican and Democratic, are now watching with a surgical eye. The stakes are immense, shaping not only who represents a Texas that is today barely 40 percent white, but also how far Republican-controlled legislatures in other states can push the mid-decade map grab. The question is whether the federal courts, after a period of near-total dormancy, are willing to step back in and tell them to finally put the crayons down. The Texas case acts as a harsh, clinical reminder that even the most sophisticated political schemes can be undone by the simple, inconvenient fact of judicial evidence. The state’s desperation to maintain power through geometry, rather than through persuasion, remains the core, unstable truth.

The Part They Hope You Miss

The deeper, more troubling implication of the El Paso ruling is not the five lost seats, but the nakedness of the attempt itself. What the trial revealed was a political establishment so confident in its structural impunity that it barely bothered to cover its tracks. The emails, the explicit orders, the technical dismantling of minority representation—it was all treated as a mere administrative function. The map was not designed to reflect the will of the people, but to preempt it, to functionally rewrite the results of future elections before a single vote was cast. That kind of profound institutional disrespect, the casual conviction that the constitution can be circumvented with clever line work, is the poison that lingers after the celebration fades. The fight now moves to Washington, where Texas will ask the highest court to validate their precise, documented efforts to silence the voices of a growing demographic. The state is asking for permission to continue the architectural construction of a permanent, minority rule.