Every few years, America remembers that it is technically a democracy, dusts off its maps, and starts drawing lines like a toddler with too many crayons and not enough supervision. This week, that coloring session moved to the Supreme Court, where the justices heard oral arguments in the latest Voting Rights Act showdown out of Louisiana. Depending on who you ask, this case will either preserve the last working guardrail of multiracial democracy or finally liberate America from the tyranny of considering other people.

Democrats and civil rights groups warn that the stakes are existential. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act — the part that says minority voters should actually get a fair chance to elect someone who represents them — is once again under threat. Republicans, meanwhile, argue that the time for “race-conscious remedies” has passed, and that the best way to prove racism is over is to make it illegal to notice it. It’s the political equivalent of curing a fever by throwing away the thermometer.

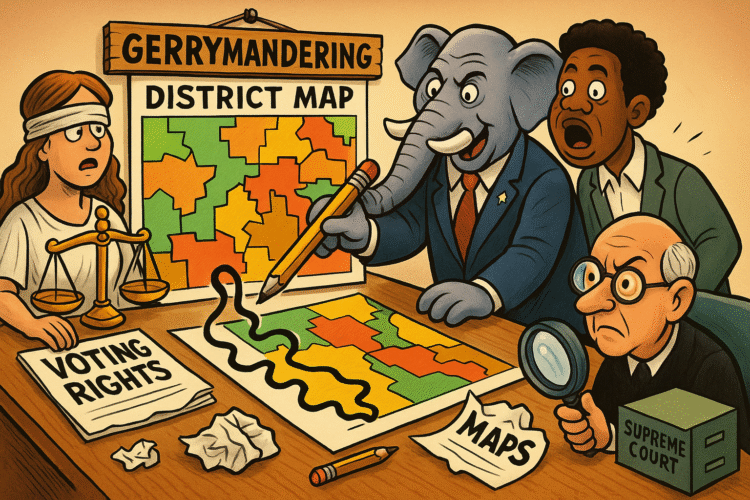

The Cartography of Power

Redistricting has always been the fine art of pretending that math is destiny while quietly deciding whose math counts. The Louisiana dispute began when mapmakers drew lines that gave Black voters — who make up roughly one-third of the state — just one effective district out of six. When a federal court called that discriminatory, the state appealed. Now the Supreme Court, with its six-member conservative bloc, is poised to decide whether that kind of map is a statistical fluke or a structural feature.

Inside the marble fortress, the questions were as delicate as a hand grenade. Conservative justices pressed the idea that Section 2 cannot justify drawing districts “based on race,” suggesting any such remedy must expire, like milk. Liberal justices countered with the radical notion that if you crack minority communities into fragments for decades, they tend not to win elections. But nuance isn’t the Court’s current mood. This is an era where constitutional interpretation is performance art, and logic is just set dressing for ideology.

How to Fix a Problem Without Fixing It

The conservative argument follows a neat circular logic: race-conscious remedies are unfair because they take race into account. The problem, of course, is that discrimination itself takes race into account, but no one ever calls that “unfair” — just “tradition.” Section 2 exists precisely because “colorblind” mapmaking has never produced colorblind outcomes. But pretending equality has already arrived is easier than maintaining it, and certainly more profitable for consultants.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who has spent his career treating the Voting Rights Act like a Jenga tower, once again seemed eager to remove a piece and call it progress. Justice Alito mused about “perpetuating racial division,” as though gerrymandering were a family dispute at Thanksgiving rather than a calculated strategy to dilute power. Meanwhile, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson reminded her colleagues that Congress didn’t write the Act to protect abstractions but to ensure that actual human beings could elect someone who might answer their phone calls.

Maps and Metaphors

If democracy is a game, maps are the scoreboard. They determine who starts on offense and who never gets the ball. In Louisiana, that translates to whether Black voters — who reliably support Democrats — can influence two congressional seats or remain locked into one. The difference may decide control of the U.S. House, which explains why so many high-minded constitutional debates sound suspiciously like campaign strategy meetings.

Across the South, similar cases are bubbling: Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina. Each dispute offers the same moral geometry — the right angles of law bending around the curves of power. The Court’s decision could effectively standardize disenfranchisement, giving states a permission slip to redraw maps mid-decade whenever demographics shift. It’s the legislative version of changing the rules after the other team scores.

The Liberal Panic and the Conservative Calm

Outside the Court, Democrats sounded the alarm. Party strategists estimate that gutting Section 2 could put a dozen House seats at risk, primarily in states where minority voters already walk a tightrope between representation and tokenism. Civil rights groups warned that weakening the Act would be “the final blow” to multiracial democracy — which is, admittedly, a phrase we’ve been recycling since at least Shelby County v. Holder.

Republicans, for their part, struck a more serene tone. They insist that America is now so gloriously diverse that majority-minority districts are obsolete. “Representation can thrive without racial quotas,” one GOP official told reporters, ignoring that “representation” in this context means “none.” It’s a masterclass in linguistic minimalism — saying less to achieve more.

Meanwhile, in New York…

As the Supreme Court debates whether race still matters in voting, New York’s top court just upheld a law moving local elections to even-numbered years to boost turnout. The move, ostensibly about convenience, also conveniently helps Democrats, whose base votes more reliably in high-turnout cycles. Republicans called it a power grab, which is technically accurate, though it’s also a power grab to deny people the right to vote in the first place.

So while Louisiana fights over who draws the lines, New York fights over when people can cross them. The contrast is poetic: one side shrinking democracy with a scalpel, the other expanding it with a calendar. Both are using the courts as the arbiter, because in 2025, judicial supremacy is America’s real form of government.

Judicial Fan Fiction

The current Supreme Court operates like a fan-fiction writers’ room for the Founding Fathers — a place where personal fantasy meets historical revision. The conservatives imagine a colorblind Constitution written by men who owned slaves. The liberals imagine an institution still capable of shame. The rest of us imagine what it would be like if we could just vote without hiring a lawyer.

When Justice Clarence Thomas waxes poetic about “the evils of racial classification,” he rarely acknowledges that the only reason he holds his seat is because of the very civil rights infrastructure he now dismantles. Justice Gorsuch, meanwhile, seemed troubled by the idea that “race might dominate the process,” as if centuries of domination weren’t enough to establish precedent.

The real question isn’t whether Section 2 survives; it’s whether democracy does. Every erosion of the Voting Rights Act has been sold as modernization, streamlining, efficiency. It’s deregulation dressed as reform, with the same ultimate goal: to shift accountability upward and participation downward.

What Happens When the Lines Move Twice

If the Court sides with Louisiana, expect a cartographic earthquake. States could redraw congressional maps again before the 2026 midterms, compressing candidate filing windows and scrambling election infrastructure. County clerks will have to retrain poll workers, campaigns will have to rewrite strategies, and voters will have to relearn which district they live in.

It’s chaos by design. Confusion is a form of suppression. Every barrier between a citizen and the ballot box — even the cognitive barrier of “I don’t know where to vote anymore” — tilts the scales toward those who prefer fewer people voting. The brilliance of modern disenfranchisement is its plausible deniability: no one is ever explicitly barred, just quietly lost.

The Math of Representation

Representation is not arithmetic; it’s architecture. The Voting Rights Act was meant to ensure that political structures reflect the communities they serve. Without Section 2, that structure collapses into an illusion — a democratic façade where choice exists in theory but not in outcome.

Imagine a state where one-third of the population is Black, yet only one of six districts can elect a Black-preferred candidate. The math is impeccable, the democracy is not. What the Court must decide is whether the law protects math or meaning.

The Partisan Symmetry Mirage

Republicans claim they simply want “neutral” maps that ignore race altogether. But neutrality is not neutrality when the baseline is bias. The current doctrine of “colorblindness” functions as a Trojan horse for entrenching power — the moral cousin of pretending not to see class while cutting taxes for billionaires.

Democrats, for their part, are not saints of cartographic virtue. Their blue-state equivalents manipulate district lines with equal cynicism; they just call it “fair representation.” But the difference lies in scale: gerrymandering in Illinois gives Democrats a few extra seats. Gerrymandering in the Deep South erases entire communities.

The Court of Public Opinion

Public faith in the Supreme Court has cratered, and cases like this explain why. Each new decision reads less like jurisprudence and more like performance art for cable news. The justices have become characters in a serialized drama — Alito the cynic, Roberts the conflicted patriarch, Jackson the moral center, Barrett the inscrutable ingénue. America tunes in not to learn the law but to watch the season finale of its own legitimacy.

Civil rights lawyers are already drafting the sequel: a congressional fix that will die in committee. Activists plan marches that will trend for a weekend before fading under the weight of scandal fatigue. The machinery of outrage spins on, as reliable as the tide.

Democracy’s Attention Span

The cruelest irony is that democracy’s biggest threat isn’t apathy — it’s exhaustion. The constant churn of crises wears down even the most devoted citizens. Each new court fight feels both vital and futile, another front in a war without end.

That’s why Section 2 matters. It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t trend. But it’s the difference between participation and performative consent. Strip it away, and elections become ritual theater — ballots as props, citizens as extras.

Drawing the Future

As the justices deliberate, mapmakers wait like stagehands. Governors refresh their inboxes for instructions. Consultants run simulations to see how many Black voters can be packed or cracked without triggering another lawsuit. Democracy, meanwhile, holds its breath, wondering how long it can survive as an experiment before becoming a museum exhibit.

If the Court narrows Section 2, it will claim to be restoring fairness. In practice, it will restore hierarchy. And once again, the people who built the country will find themselves redistricted out of it.

The Unwritten Line

What happens next will depend less on legal doctrine than on political will. Congress could restore the Act tomorrow, but that would require a bipartisan interest in shared power — an oxymoron in 2025. Voters could demand accountability, but that would require elections stable enough to reflect their demands.

In the end, this is not about Louisiana. It’s about whether America still believes in the premise of representation or has resigned itself to the convenience of control. The Voting Rights Act was the nation’s promise that democracy would be more than arithmetic. If that promise breaks, the lines on the map will no longer mark districts. They’ll mark the boundaries of belief.

And maybe that’s the most honest map of all — a country divided not by geography, but by whether it still cares to be governed by the governed.