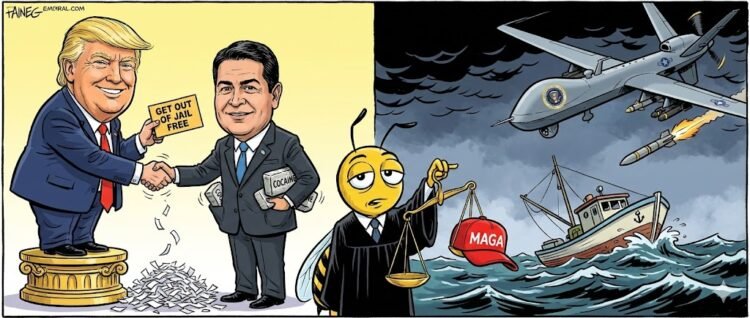

The American capacity for cognitive dissonance is usually impressive. It is the engine that keeps the suburbs quiet and the stock market humming. But on November 28, 2025, President Donald Trump decided to test the structural integrity of that engine by pouring sugar, sand, and a few gallons of high-grade cocaine directly into the gas tank. In a move that redefines the concept of “law and order” as a punchline to a joke that only autocrats find funny, Trump announced a full pardon for Juan Orlando Hernández. For those who do not follow the intricacies of Central American narco-politics, Hernández is the former President of Honduras who was extradited to the United States in 2022, convicted by a federal jury in 2024, and sentenced to forty-five years in prison. His crime was not a minor bookkeeping error or a lapse in judgment. It was helping to move hundreds of tonnes of cocaine into the United States, turning his entire government into a concierge service for the Sinaloa Cartel.

The pardon itself is a breathtaking act of vandalism against the concept of justice. It takes a conviction secured by the hard work of career prosecutors—who spent years untangling a web of violence, bribery, and state-sponsored trafficking—and tosses it into the Potomac because the defendant wears a suit and speaks the language of right-wing populism. Trump framed the move as correcting an “injustice,” validating the conspiracy theory that Hernández was merely a victim of political targeting. In doing so, he has effectively declared that if you are a drug lord who is also a head of state and a “friend” of the MAGA movement, the federal drug statutes are merely suggestions.

But the true, vertigo-inducing horror of this announcement is not the pardon itself. It is the context in which it lands. At the exact same moment the President is signing the papers to free a man who facilitated the poisoning of American communities on an industrial scale, his administration is waging a kinetic, lethal war on the lower rungs of the drug trade that would make a Hollywood action director blush.

This White House claims sweeping authority to strike “suspected” narcotics vessels in international waters. We have seen the grainy footage. We have heard the reports from rights groups and legal scholars. The United States military is using lethal drone strikes and naval cannon fire to vaporize small boats in the Caribbean and the Eastern Pacific. These operations are often conducted without public evidence, without due process, and with a terrifying disregard for the possibility—or probability—that the people on those boats are fishermen, migrants, or low-level mules forced into service by the very cartels Hernández empowered.

The juxtaposition is so stark it feels like a glitch in the simulation. On one screen, we have the President using the imperial power of the pardon to liberate a man who ran a narco-state. On the other screen, we have the President using the imperial power of the drone to execute people who might be moving a few kilos. It creates a hierarchy of crime where the magnitude of the offense is inversely proportional to the punishment. If you smuggle a backpack of drugs, you are a target to be destroyed. If you facilitate the smuggling of a shipping container of drugs, you are a statesman to be rehabilitated.

This is the new logic of the American empire in 2025. The War on Drugs is no longer a crusade against narcotics. It is a class war disguised as a security operation. It is a system where the “kingpin” designation is not a mark of shame, but a membership card to a club where the dues are paid in loyalty to Donald Trump. Hernández is being pardoned not because he is innocent, but because he is useful. He is a conservative. He is an ally in the administration’s efforts to reshape the regional balance of power in Central America. He is a tool to be used against the leftist governments in the region. And in the transactional moral universe of this White House, political utility washes away all sins, even if those sins involve turning a nation into a landing strip for El Chapo.

The pardon of Hernández is a signal flare sent up from the White House lawn, visible from Tegucigalpa to Bogota. It tells every corrupt leader in the hemisphere that the United States is no longer in the business of fighting corruption. We are now in the business of franchising it. If you align yourself with the political goals of the Trump administration, if you echo the rhetoric about “globalists” and “socialists,” if you promise to keep the migrants on your side of the border, you can do whatever you want. You can loot your treasury. You can work with the cartels. You can dismantle your courts. And if the “deep state” prosecutors in New York try to touch you, the President will be there with the golden pen to set you free.

It undercuts decades of U.S. diplomacy. For years, American ambassadors have lectured Latin American leaders on the importance of the rule of law. They have tied aid packages to judicial reforms. They have demanded the extradition of traffickers. That entire architecture of soft power has been incinerated in a single afternoon. How does a U.S. diplomat walk into a meeting in Mexico City or Guatemala City and demand action against corruption when their boss just let the biggest fish in the tank go free? They don’t. They can’t. The moral high ground has been sold for parts.

The fallout will be immediate and catastrophic. Human rights groups are already drafting the press releases that no one in the West Wing will read. They will point out the hypocrisy of pardoning a man whose administration was linked to death squads and the murder of activists like Berta Cáceres. They will note that this pardon is a slap in the face to the Honduran people who risked their lives to testify against him, who fled the violence he engineered, and who are now watching from asylum centers in the U.S. as their tormentor gets a first-class ticket home.

But the administration is banking on the cynicism of the American public. They are betting that the average voter does not know who Juan Orlando Hernández is, and does not care. They are betting that the base will hear “political target” and nod along, accepting the narrative that the same prosecutors who indicted Trump must have framed Hernández. It is a unified theory of victimhood, a global alliance of the aggrieved powerful. Trump sees himself in Hernández. He sees another strongman persecuted by the legal system, another leader hounded by “fake news” and “radical prosecutors.” The pardon is an act of narcissistic empathy. He is not saving Hernández; he is symbolically saving himself.

Meanwhile, in the waters off the coast of Central America, the drone operators are still working. The “suspected” vessels are still being tracked. The missiles are still being fired. The administration justifies these extrajudicial killings as a necessary measure to stop the flow of drugs, to protect the American homeland from the scourge of fentanyl and cocaine. They use the language of war to justify the summary execution of people whose names we will never know.

This is the grim reality of the “two-tiered” justice system the right loves to complain about. But the tiers are not defined by political party. They are defined by power. If you have a motorcade, you get due process, endless appeals, and eventually, a pardon. If you have a wooden boat and a malfunctioning engine, you get a Hellfire missile.

The pardon sets up a near-term cascade of consequences that will likely paralyze what remains of our regional partnerships. Congressional oversight hearings will be scheduled, where Democrats will fume and Republicans will stare at their shoes or mutter about “sovereignty.” Diplomatic strain with regional partners who actually want to fight cartels will reach a breaking point. Why should Colombia or Panama cooperate with the DEA if the endgame is a presidential pardon for the boss? The entire incentive structure of international law enforcement has been inverted.

We are also facing the terrifying precedent of pardoning a foreign official convicted in a U.S. court. This is a new frontier in the abuse of executive power. It suggests that the President views the federal judiciary not as a co-equal branch of government, but as a subordinate agency whose work can be undone whenever it inconveniences his foreign policy whims. It transforms the federal courts into a kangaroo court where the verdict only sticks if the President agrees with it.

The cynical campaign stunt aspect cannot be ignored. Trump is explicitly backing conservative Honduran candidates. He is trying to engineer a right-wing restoration in the region. Pardoning Hernández is a way to rally the old guard, to show that the U.S. is back in the business of propping up “our bastards.” It is a return to the darkest days of the Cold War, where we supported dictators and death squads as long as they were anti-communist. The only difference is that now, we support them as long as they are “anti-woke.”

As we digest the turkey and the tyranny, we must reckon with what this says about us. We are a nation that locks up its own citizens for decades for possessing minor amounts of narcotics. We have filled our prisons with Black and brown bodies in the name of the War on Drugs. We have destroyed generations of families over ounces. And yet, we have a President who looks at a man responsible for moving tons—literal tons—of cocaine and sees a kindred spirit.

The message is clear. The crime is not the drugs. The crime is being small. If you are a small-time dealer, you are a monster. If you are a president who turns your country into a cocaine logistics hub, you are a statesman who was treated unfairly.

This is the ultimate triumph of realpolitik over morality. It is the final admission that the United States government does not care about drugs, or crime, or justice. It cares about power. It cares about control. And it will ally itself with anyone, no matter how much blood is on their hands, if it serves the momentary interests of the man in the Oval Office.

The drone strikes will continue. The press releases about “border security” will continue. The demonization of the addict and the mule will continue. But the kingpin is going home. He will likely return to a hero’s welcome from his faction, emboldened by the seal of approval from the United States. And somewhere in the Caribbean, a boat will explode, and the water will close over the evidence, and the war will go on, safe for the generals but deadly for the soldiers.

The Cartel of One

The ultimate irony is that Donald Trump has effectively positioned himself as the Don of the hemisphere. He decides who is a criminal and who is a partner. He decides who lives and who dies in the international waters. He has centralized the power of life and death, of prison and freedom, into his own hands. The pardon of Juan Orlando Hernández is not an act of mercy. It is an act of dominance. It is a reminder that in 2025, the law is whatever the President says it is, and the only crime that is unforgivable is disloyalty to the throne. The “War on Drugs” hasn’t ended; it has just been privatized, and the new CEO has decided that the competition is illegal, but the partners are too big to jail.