The Justice Department keeps pulling the lever, and the indictment machine keeps blinking “try again” like it’s a broken arcade game with federal letterhead.

There are a few sacred American traditions you can set your watch by, even if nobody can agree what time it is anymore. One is that a federal grand jury will usually do what prosecutors ask. Another is that when power gets embarrassed, it rarely steps back, it just changes the lighting and calls it a new angle. This week delivered a rare gift: a grand jury in Virginia’s Eastern District declined to indict New York Attorney General Letitia James, and then, because we are apparently speedrunning the concept of norms, another grand jury in the same district declined again, days later, in a different city. The federal system, famous for its win rate in grand jury rooms, just went zero for two, and you could practically hear the collective inhale from every person who still keeps the word “credibility” on the shelf.

The setting matters because Eastern District of Virginia is not a sleepy side room in the federal courthouse universe. It is a venue prosecutors like because it moves fast, hits hard, and tends to be reliable, especially when the government shows up with statutes, charts, and that familiar tone that says, “We are not here to debate.” The first grand jury sat in Norfolk. The next sat in Alexandria. Two different rooms, two different sets of citizens sworn to weigh the evidence, and both responded with the same blunt syllable that has become the rarest sound in the federal criminal process: no.

The Case That Wouldn’t Stay Dead

The basic allegation, as framed by prosecutors, is that James misrepresented details tied to a home purchase in the pandemic-era housing frenzy in order to secure favorable loan terms. The charges the Justice Department has been angling toward fall under 18 U.S.C. § 1344, bank fraud, and 18 U.S.C. § 1014, false statements to influence a financial institution. These are not obscure statutes that only appear when someone says “wire transfer” three times into a mirror. They are serious, commonly used tools, and in most cases prosecutors do not bring them unless they believe they can walk a jury through the story without losing the room.

What makes this episode feel like a fever dream is not just the double refusal, but the fact that the case has already been through a procedural trapdoor. An earlier indictment was tossed out by a judge because the U.S. attorney who brought it, Lindsey Halligan, was unlawfully appointed. That is not a minor typo. That is the government showing up to court with the wrong key, insisting the door still counts as open, then acting offended when the judge points out that the law has an opinion about who gets to prosecute people in the name of the United States.

So the Justice Department, having watched its first attempt get dismissed on procedural grounds, came back and tried again. And then again. And now, after two grand juries declined to indict in quick succession, the department has still not ruled out trying yet again, which is how you know we are no longer talking about ordinary law enforcement decision-making. We are talking about institutional stubbornness, reputational damage, and the kind of determination that stops being about the evidence and starts being about not letting the headline win.

James has denied wrongdoing and has called the prosecution politically motivated. That claim is not coming from nowhere in the current climate. James is a Democrat, an outspoken critic of President Donald Trump, and the attorney general who secured a civil fraud judgment against him last year. If you are looking for a clean way to frame this for the public, good luck. Even people who would normally insist the Justice Department lives on a mountain made of neutral marble can recognize the optics when a high-profile Trump antagonist becomes the target of persistent federal charging efforts that keep sputtering out in grand jury rooms.

Grand Juries, Not Supposed to Have Spines

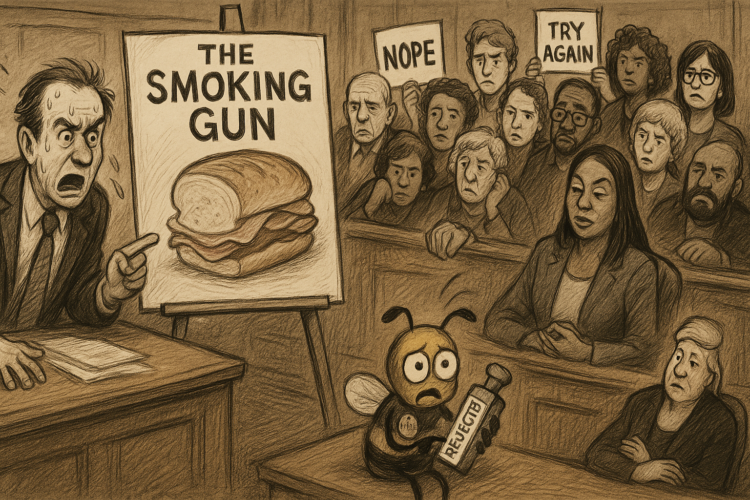

The part that should make your teeth hurt is how unusual it is for a federal grand jury to refuse an indictment, especially after prosecutors have already decided they want one. The phrase “a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich” became popular for a reason. It reflects the reality that prosecutors control what evidence is presented, how it is framed, and what legal standards are emphasized. Grand juries do not hear the defense case in the same way a trial jury would. They do not get the full adversarial spectacle. They get the government’s presentation, and they are asked to decide if there is probable cause, a low bar that can be cleared by an average dog with a good running start.

When citizens sitting in that room decide to say no anyway, something unusual is happening. Either they were unconvinced by the evidence. Or they were disturbed by the context. Or they read the room in a way the prosecutors misjudged. Or they simply decided they were not going to be used as a stamp in a process that looked like it had already chosen its conclusion.

That is what makes the back-to-back refusals land like a siren. One refusal can be chalked up to presentation problems, witness issues, or a case that needed more tightening. Two refusals in rapid sequence, in two different grand jury locations, after a prior dismissal for procedural defects, starts to look like a collective civic flinch. It looks like ordinary people were asked to participate in something that felt off, and they declined to play their assigned role.

Legal observers have criticized the department’s persistence as damaging to institutional credibility. That critique is not a partisan talking point, it is a practical warning. The Justice Department is supposed to have discretion not just to prosecute when it can, but to avoid prosecutions that weaken public trust. When the department appears to be shopping for a grand jury that will finally do what it wants, it invites the public to conclude that the process is about persistence, not proof. It turns prosecutorial judgment into a stubborn dare.

The Appointment Problem That Should Have Ended the Conversation

The procedural defect that killed the first indictment is the kind of mistake that should make everyone in the building stop and ask what else is sloppy. A judge ruled that the U.S. attorney who brought the original indictment was unlawfully appointed. That is not a judgment about the underlying facts of the alleged mortgage fraud, but it is a judgment about the government’s right to haul someone into criminal court. When the appointment is unlawful, the case is compromised at the root.

In a healthier timeline, that would trigger restraint. You fix the appointment problem, review the case, and decide whether the merits justify restarting the whole machine. You do it carefully, aware that the public has already seen the government trip. You do it in a way that does not look like a revenge sequel.

Instead, we got the double grand jury refusal, which suggests the Justice Department is not only trying to rebuild the case procedurally, but to force it into existence through repetition. That is where it starts to feel less like prosecution and more like narrative management. It is the government acting like it can outlast the skepticism in the room if it just keeps sending the same script to different casts.

And the casts keep refusing.

The Political Gravity Under the Legal Paperwork

It would be irresponsible to pretend this story exists in a political vacuum, because the vacuum has been out of order for years. James built a national profile through her legal battles with Trump. Trump built his modern persona by treating institutions as enemies when they constrain him and trophies when they serve him. When those two storylines collide in federal court, everyone’s motives get interrogated, whether or not the underlying facts justify the charges.

James says this is politically motivated. The administration and its allies can insist it is merely about the law. Both statements can be partially true in different ways, which is what makes the moment so destabilizing. Even if the allegations involve real misrepresentations, the department’s persistence, especially after being slapped for an unlawful appointment, makes it harder to sell the story as neutral. And even if the department truly believes the case is strong, the optics of repeatedly seeking an indictment against a prominent Trump antagonist invites the public to see the prosecution as part of a broader political project.

That perception is not a side issue. It is the issue, because institutions run on consent. Not the consent of people who already agree with them, but the consent of people who do not. When a Justice Department is perceived as weaponized, every future prosecution becomes harder to legitimize, even the ones that are clean, necessary, and urgent. That is how institutional credibility gets eaten from the inside, one stubborn decision at a time.

The DOJ’s Dangerous Temptation: Try Again, But Louder

The department has not ruled out trying yet again. That sentence should make anyone who cares about legal norms sit up straighter. There is a difference between building a better case and trying to outwear resistance. The first is what competent prosecutors do. The second is what organizations do when they can’t accept a public “no,” especially when that “no” comes from ordinary citizens in a room that is usually treated as a formality.

There is also a strategic problem here: the more the department tries and fails, the more it trains the public to view the case as suspect. Every new attempt becomes part of the defense narrative. If prosecutors eventually do secure an indictment, half the country will treat it as proof of persistence rather than proof of guilt. If prosecutors never secure an indictment, the other half will treat the repeated attempts as proof of harassment. Either way, trust loses.

This is the kind of spiral that convinces people the legal system is just another battlefield. Once that belief sets in, it does not stay neatly confined to one case. It spreads. It becomes the default lens through which people see investigations, prosecutions, plea deals, and sentencing. It becomes the reason jurors show up already suspicious. It becomes the reason witnesses hesitate. It becomes the reason every outcome gets interpreted as political.

And it becomes the reason the Justice Department, an institution that desperately needs to be believed, gets treated like one more partisan actor in a crowded market.

The Quiet Hero Here Is Bored Civic Duty

Grand jurors are not celebrities. They do not get book deals. They do not get to grandstand on cable news about how they heroically refused to rubber-stamp a prosecution. Their work is often tedious, private, and thankless. The system depends on their willingness to listen, to weigh, and to take the task seriously even when the lawyers in the room speak in the confident tone of inevitability.

That is why the double refusal matters. It suggests that, at least in these rooms, citizens took their role seriously enough to resist the gravitational pull of “the government wants this, so it must be right.” It suggests they treated probable cause as a real threshold, not a decorative phrase.

It also suggests something else: people can smell when a process is being used to stage a point. They might not know every legal nuance, but they know when the vibe is off. They know when the story being sold feels like it belongs to a bigger feud rather than a clean enforcement action. They know when they are being asked to put their name on a decision that will be used as a political weapon, regardless of the merits.

That instinct, that collective reluctance, is one of the few remaining checks that doesn’t require a lawsuit, a campaign, or a billionaire. It requires citizens willing to sit in a room and say, “I’m not convinced.”

The Institutional Self-Inflicted Wound

Even people who dislike James, or distrust her politics, should be able to see the risk here. A Justice Department that appears to chase a political opponent, especially through repeated grand jury attempts after procedural embarrassment, is not just harming one person. It is harming itself. And when that institution harms itself, it harms everyone who relies on it to prosecute real corruption, real fraud, real violence, and real abuses of power.

The irony is that this episode may end up strengthening James politically. Nothing builds a politician’s brand like being targeted in a way that looks unfair. The prosecution effort, if perceived as partisan harassment, becomes a shield and a rallying cry. It turns a technical allegation about a mortgage transaction into a larger story about power retaliation. It gives her allies a clean message and it gives the public a simple narrative: they keep coming for her because she went for him.

Meanwhile, the department looks like it is throwing its weight around without landing a punch. In a system where prosecutors almost always get indictments, failing twice in a row is not a routine misstep, it is a headline that signals doubt. And doubt is contagious.

What This Means for Norms When Everyone Wants a Trophy

The bigger concern is what this reveals about prosecutorial priorities in a politicized era. The Justice Department has limited resources and endless targets. The choices it makes signal values. If it spends heavy effort pushing a contested case against a high-profile political figure, in the face of repeated grand jury skepticism, it invites questions about why. Not just why this case, but why this insistence. Why now. Why again.

Those questions do not vanish even if prosecutors believe they are right. In fact, the more prosecutors insist, the more the public asks whether the insistence is doing work that the evidence cannot.

This is where the mock-serious historian voice gets to take notes in real time: when institutions feel attacked, they sometimes respond by acting like the attackers. They become less restrained, more combative, more focused on winning than on being trusted. They stop thinking like stewards and start thinking like players. The Justice Department cannot afford that transformation, because it is not supposed to be a faction. It is supposed to be a floor, a baseline, a guarantee that the rules mean something even when the politicians are screaming.

If the department turns into one more tool for political narratives, the country loses one of the last remaining places where the word “law” can still pretend to mean something stable.

Receipt Time The Indictment That Couldn’t Clear the Room

Two grand juries in the same federal district heard the government’s pitch in two different cities and both declined to indict, after an earlier attempt was already thrown out because the prosecutor’s appointment was unlawful, and the only thing more alarming than the repeated failure is the suggestion the department might keep trying until someone finally says yes. That is not persistence that builds confidence, it is persistence that broadcasts need, and need is not what the public should ever smell on the breath of a Justice Department. When citizens in that room decide the government has not earned the next step, the institution’s job is to listen, not to shop for a new room.