When the penalty for smuggling is a Hellfire missile, we have not won the War on Drugs; we have simply decided to stop taking prisoners.

The American legal system is famously obsessed with procedure. We have entire libraries filled with books about the rights of the accused, the rules of evidence, and the precise geometric dance that must occur before the state is allowed to take away a citizen’s freedom, let alone their life. If you are caught selling heroin on a street corner in Baltimore, you are entitled to a lawyer. You are entitled to a trial. You are entitled to a jury of your peers who will sit in a cold room and decide if the baggie in your pocket is actually yours. Even if you are a kingpin, a monster who has flooded a community with poison, you will be arrested, handcuffed, and processed. You will wear an orange jumpsuit, not a toe tag. This is the compact of civilization. We punish the crime, but we do not execute the criminal in the street without a judge’s signature.

Unless, of course, you are on a boat in the Caribbean.

In the open waters south of Florida, the Constitution dissolves into salt spray. The careful architecture of due process is replaced by the blunt trauma of a Hellfire missile. We have entered a new and terrifying phase of the drug war where the penalty for smuggling is no longer a prison sentence but an extrajudicial death. The recent revelations about U.S. military strikes on “narco-terrorist” vessels reveal a policy that has graduated from law enforcement to summary execution. We are not arresting these men. We are vaporizing them. And we are doing it under a legal theory that is as thin as the oil slick left behind on the water.

The administration defends these strikes as necessary acts of self-defense against “narco-terrorism,” a hyphenated buzzword that does a lot of heavy lifting. By attaching “terrorism” to “narcotics,” the government grants itself the permission to treat a smuggler like an enemy combatant. A drug dealer is a criminal who has rights. A terrorist is a target who has coordinates. It is a linguistic sleight of hand that allows the Department of Defense to bypass the Department of Justice. It turns a crime scene into a battlefield, where the rules of engagement are loose and the oversight is classified.

The absurdity of this policy is magnified when you look at the actual chemistry of the overdose crisis. The administration claims these strikes are necessary to save American lives, citing the horrific toll of the fentanyl epidemic. Roughly 110,000 Americans die every year from overdoses, a tragedy that touches every community in the nation. But here is the inconvenient fact that ruins the narrative: the boats we are blowing up are largely carrying cocaine. Fentanyl, the synthetic killer responsible for the vast majority of those deaths, does not typically arrive on go-fast boats from Venezuela. It starts as precursor chemicals in China, travels to labs in Mexico, and crosses the land border in trucks and passenger cars.

Bombing a cocaine boat to stop the fentanyl crisis is like bombing a brewery to cure alcoholism. It is a non-sequitur of violence. It is theatrical force applied to the wrong target for the sake of looking tough. Cocaine is certainly harmful, but it is not the driver of the mass death event we are witnessing. Yet cocaine moves by sea, and boats make for better target practice than a semi-truck at a crowded border crossing. The administration needs a spectacle. They need an explosion. They need to show the voters that they are “doing something,” even if that something is kinetically dismantling a supply chain that is largely irrelevant to the primary threat.

This incoherence exposes the dark truth of our current posture. We are not fighting a war on drugs. We are fighting a war on optics. The fentanyl crisis is complex, diplomatic, and logistical. It requires arm-twisting Beijing and working with Mexico City. It requires port scanners and intelligence. It is boring, difficult work. Blowing up a boat in the Caribbean is easy. It provides a visual of American power. It satisfies the urge for vengeance. It allows the Secretary of Defense to post a video of an explosion and claim a victory. The fact that the explosion didn’t save a single life in Ohio or West Virginia is a detail that gets lost in the smoke.

But if the disconnect between the target and the threat is absurd, the disconnect between our foreign and domestic policies is grotesque. Inside the United States, we have slowly, painfully moved toward a medical model of addiction. We recognize that substance abuse is a disease. We talk about harm reduction. We have largely agreed that we cannot arrest our way out of this problem. Yet the moment the drugs cross the border, the philosophy shifts from public health to total war. The dealer in Chicago is a criminal to be prosecuted; the smuggler in the Caribbean is a combatant to be annihilated.

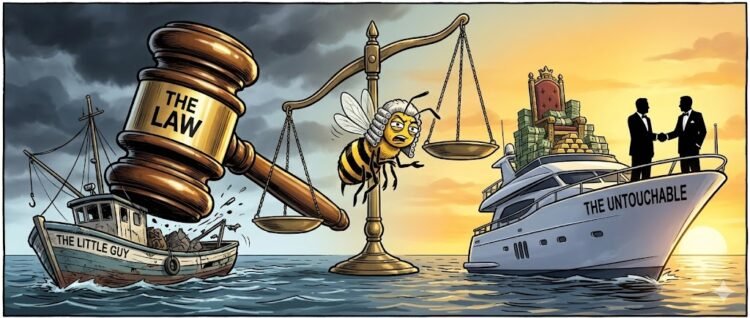

Why is the life of a low-level mule on a boat worth less than the life of a dealer on a corner? Both are cogs in the same machine. Both are likely motivated by poverty and desperation. Yet one gets a public defender and the other gets a drone strike. It is a geographical morality, a system where your rights depend entirely on your GPS coordinates. If you are on land, you are a person. If you are at sea, you are a pixel on a screen, waiting to be deleted.

And then there is the pardon.

If you want to understand the true rot at the core of this policy, you have to look at the case of Juan Orlando Hernández. The former President of Honduras was not a low-level smuggler. He was a head of state who turned his entire country into a cocaine superhighway. He didn’t move kilos; he moved tons. He used the police and the military to protect shipments. He took millions of dollars in bribes from cartels. He was, by any definition, the ultimate “narco-terrorist,” a man who used the power of the state to flood the United States with poison.

He was convicted in a U.S. federal court. The evidence was overwhelming. He was sentenced to decades in prison. And then, in a stunning act of political cynicism, President Trump pardoned him.

The justification was a slurry of diplomatic nonsense about “strategic interests” and “partnership.” But the message was clear. If you are a rich, powerful, politically connected drug trafficker, you are a statesman who deserves mercy. If you are a poor, anonymous drug trafficker on a fiberglass boat, you are a target who deserves death.

This is the two-tier justice system in its rawest form. It is class warfare disguised as foreign policy. The “narco-combatant” label is reserved for the expendable. It is for the disposable men who drive the boats and drive the trucks. The men who own the boats, the men who run the countries, the men who wear suits and shake hands at summits—they are exempt. They are “partners.” They get meetings. They get pardons. They get to retire to villas while their foot soldiers get turned into pink mist.

The hypocrisy is so brazen it feels like a taunt. The administration celebrates the release of a man credibly linked to industrial-scale trafficking while simultaneously justifying the killing of anonymous smugglers. They tell us that drugs are an existential threat that justifies suspending the rules of war, but then they high-five the guy who opened the floodgates. It reveals that the “war on drugs” has never been about the drugs. It has always been about power. It has always been about who gets to break the law and who has to die for it.

We are witnessing the normalization of state violence as a substitute for policy. When you cannot solve a problem, you shoot it. When you cannot stop the flow of drugs, you blow up the delivery vehicles. It is a policy of frustration, a tantrum with a guidance system. It is the act of a superpower that has run out of ideas and has decided to rely on brute force.

But brute force has a cost. It degrades the moral authority of the nation. You cannot claim to be the champion of the rule of law while running a maritime assassination program. You cannot lecture the world on human rights while executing people without trial. Every time a missile hits a boat, we are telling the world that our principles are flexible. We are telling them that due process is a luxury we can no longer afford.

The “narco-terrorist” framework is a slippery slope that leads to a very dark place. Once you accept that drug smuggling is a capital offense punishable by summary execution, where do you draw the line? Do we drone strike the labs in Mexico? Do we bomb the chemical factories in China? Do we target the banks that launder the money? Of course not. Because those targets have political consequences. Those targets have armies. Those targets fight back.

So we pick on the weak. We pick on the boats. We pick on the targets that cannot shoot back and cannot sue. It is the bullying logic of a schoolyard, applied to geopolitics. We hit the people we can hit, not the people who deserve it.

The silence from the American public on this shift is perhaps the most disturbing part. We have become so desensitized to violence, so accustomed to the drone war, that we barely blink when we hear about a strike in the Caribbean. We assume that the government knows what it is doing. We assume that the people on the boat were “bad guys.” We assume that the ends justify the means.

But the ends are not being achieved. The drugs are still flowing. The overdose deaths are still rising. The only thing changing is the body count. We are piling corpses on top of a policy failure and calling it a strategy.

The media plays its part in this theater. They report the strikes as “interdictions.” They repeat the administration’s talking points about “security.” They rarely ask who was on the boat. They rarely ask why we are killing people for a crime that carries a prison sentence in Miami. They accept the “narco-terrorist” frame without question, allowing the government to define the terms of the debate.

We need to call this what it is. It is murder. It is state-sponsored murder of civilians for economic crimes. It is a violation of international law, domestic law, and basic morality. It is a policy that makes us no better than the cartels we claim to be fighting. The cartels kill for profit. We kill for politics. Is there really a difference?

The pardon of Juan Orlando Hernández should have been the moment the illusion shattered. It should have been the moment we realized that the “war on drugs” is a rig. It proved that the system is designed to protect the powerful and punish the weak. It proved that justice is a commodity that can be traded for favors.

Yet the boat strikes continue. The missiles keep flying. And the administration keeps bragging about its toughness. They are tough on the symptoms, but soft on the cause. They are tough on the poor, but soft on the rich. They are tough on the water, but soft in the courtroom.

The contrast between the domestic reality and the foreign policy fantasy is unsustainable. You cannot treat addiction as a disease at home and a war crime abroad. You cannot have drug courts in Ohio and kill zones in the Caribbean. Eventually, the cognitive dissonance will crack the foundation. Eventually, we will have to decide if we are a nation of laws or a nation of violence.

Right now, we are choosing violence. We are choosing the easy path of destruction over the hard path of justice. We are choosing to be a hammer in a world of nails.

But the nails are human beings. And the hammer is getting heavy.

The tragedy of the overdose crisis is real. The pain of the families who have lost loved ones is real. But vengeance is not a cure. Killing a smuggler does not bring back a child. It does not stop the next shipment. It just adds another death to the tally.

We are trying to solve a public health crisis with military hardware. It is a category error of the highest order. It is like trying to perform surgery with a bayonet. You will not fix the patient. You will only make a mess.

The “narco-combatant” is a fiction. He is a criminal. He deserves a trial. He deserves a sentence. He does not deserve to be erased from the earth by a robot in the sky. When we accept that he does, we lose something of ourselves. We lose the claim that we are different. We lose the claim that we are just.

The pardon of Hernández proves that we don’t even believe our own rhetoric. If we really believed that drug trafficking was an act of terrorism, Hernández would be in Guantanamo. Instead, he is free. He is proof that the rules are for the little people.

The United States was built on the idea that no person is above the law, and no person is beneath it. But in the Caribbean, we have decided that some people are beneath the law. They are beneath the dignity of a trial. They are beneath the right to life. They are just obstacles to be removed.

And Juan Orlando Hernández? He is above the law. He is in the stratosphere of the untouchable.

This is the state of our union. We have missiles for the mules and mercy for the kings. We have death for the desperate and deals for the dictators. We have a war on drugs that is actually a war on the poor.

And we wonder why we are losing.

We are losing because we have lost our way. We have forgotten what justice looks like. We have confused strength with violence. We have confused vengeance with policy.

Until we remember that the law applies to everyone—even the people on the boats, even the people in the palaces—we will continue to lose. We will continue to drift. We will continue to be a nation that talks about rights while pulling the trigger.

The water in the Caribbean is blue and beautiful. But if you look closely, you can see the stain. It is the stain of our own hypocrisy. And it is not washing away.

Receipt Time

The ledger for this moral bankruptcy is written in red ink and red blood. We are spending millions of dollars on missiles to blow up boats that are worth a fraction of the cost of the munition. We are spending billions on a military deployment that has failed to stop the flow of drugs. But the real cost is not financial. The real cost is the erosion of our soul. The receipt shows a zero balance for “Rule of Law” and a massive debt for “Humanity.” We have purchased the illusion of security at the price of our principles. And the worst part is, we didn’t even get what we paid for. The drugs are still here. The only thing missing is our conscience.