On September 2, 2025, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta finally dropped his long-awaited remedy order in the Justice Department’s search-monopoly case against Google. Two-hundred and twenty-six pages of judicial prose, the kind that smells faintly of toner and resignation, landed with a thud that echoed through Washington and Silicon Valley. For all the build-up—whispers of breakup, structural remedies, maybe even a shockwave felt across Mountain View’s kombucha bars—the outcome was less guillotine, more “sternly worded curfew.”

Yes, the order bans exclusive default-search contracts across Chrome, Android, Gemini, and Assistant. Yes, it forces Google to share slices of its search index and query data with rivals, under court supervision, like a parent instructing siblings to “share the Legos.” But the rest reads like a polite thank-you note to Big Tech. No breakup. No permanent bans. No dramatic handcuffs. Just five years of oversight and the ability to keep paying billions in default-placement deals—Apple included—so long as they’re non-exclusive and time-limited.

Markets cheered. Antitrust advocates fumed. And America was left with the same question it always faces after “landmark” rulings: is this enforcement, or just performance?

The Remedy as Rhetoric

Two-hundred and twenty-six pages is a lot of words to say “we’re watching you (sort of).” The decree nods to AI’s “disruptive” potential, as though Judge Mehta were a venture capitalist offering reassurance at a fireside chat. It talks about non-exclusive deals and transparency like those words mean something. But in the end, the ruling is less hammer, more feather duster.

Google gets to keep its empire. It just has to open the drawbridge a little wider and let a few rival knights clamber around the moat. Antitrust, it seems, has been reimagined not as a shield for competition, but as a customer service manual.

The Default Problem That Isn’t Fixed

The heart of the government’s case was the default. The way Google baked itself into the fabric of everything: Chrome, Android, Gemini, Assistant. The way it funneled billions into Apple’s pockets to ensure “search” was synonymous with “Google.”

Judge Mehta’s order bans exclusivity, but non-exclusive defaults are still defaults. If Apple can take money from Google and Microsoft and DuckDuckGo simultaneously, who wins? Apple. Google keeps paying. Rivals can bid, but what chance do they have against the company that built the pipeline and owns the water?

It’s like telling Coca-Cola it can’t have exclusivity at the stadium, but it can keep buying 90% of the vending machines. Sure, Pepsi can show up. Sure, some craft soda can make a cameo. But the thirst has already been branded.

Index-Sharing: Forced Group Project

The requirement that Google share slices of its search index and query data with rivals under supervision was hailed by some as revolutionary. In reality, it’s a group project gone wrong.

Google controls the library, the index cards, the lights in the reading room. Rivals will get a few curated packets—data that is stale by the time it’s released, query samples that look generous but omit the good stuff. It’s like sharing a Netflix account but only giving your roommate access to documentaries about lichen.

Antitrust theory says this levels the playing field. Antitrust reality says: good luck building a search engine out of leftovers.

Five Years of Polite Oversight

The five-year decree is a joke wrapped in a calendar. In Silicon Valley time, five years is a century. Entire companies are born, scale, SPAC, collapse, and get acquired in less than that. By the time this decree expires, half of today’s AI startups will be defunct, the Gemini app will be an afterthought, and the metaverse will still be waiting for users.

Enforcement timelines should move faster than tech adoption cycles. Instead, the decree is the equivalent of telling Google: “We’ll check back after your next three product cycles. Don’t do anything naughty.”

Markets Applaud the Soft Landing

Wall Street, naturally, loved it. Google stock barely blinked before nudging upward. Analysts praised the decision as “balanced,” which is investor-speak for “we were terrified of an actual remedy.”

The markets didn’t see a breakup. They didn’t see a threat. They saw continuity dressed up as disruption. The default contracts continue, the cash machines hum, and the oversight is little more than a parking ticket written in cursive.

Antitrust Advocates, Perpetually Fuming

Meanwhile, antitrust hawks tore their hair out. They wanted teeth. They got gums. They wanted a message that the era of platform impunity was over. They got a decree that basically said: “We’d like you to behave better. Here are some guidelines. Please don’t make us write another PDF.”

For decades, antitrust enforcement has oscillated between toothless settlements and grandstanding trials. Judge Mehta’s order falls squarely in the middle: symbolic enough to generate headlines, weak enough to reassure markets.

The advocates can fume. The platforms can cheer. And nothing, fundamentally, changes.

AI as Distraction

Perhaps the most telling part of the ruling was the nod to AI. The decree notes that AI is “disruptive,” that the future of search is shifting, that regulation must account for these transformations. This is the new corporate strategy: wave your hands at AI like a magician, and hope the audience doesn’t notice you palming the coin.

Google’s search dominance is not an AI problem. It’s a structural problem. It’s the network effects of defaults and data, the feedback loop of scale and advertising. AI may tweak the interface, but it doesn’t change the underlying monopolization. By letting AI become the shiny object, the ruling dilutes its own focus.

The Apple Loophole

Then there’s Apple, quietly pocketing billions for making Google the default. The order allows default-placement payments to continue—so long as they’re non-exclusive and time-limited. Which means Apple can take the checks, shrug at the decree, and tell regulators: “We’re Switzerland. Anyone can pay. It just happens that Google pays the most.”

It’s the equivalent of banning exclusive nightclub access but still letting one patron buy out all the champagne. The door is technically open, but who’s getting in?

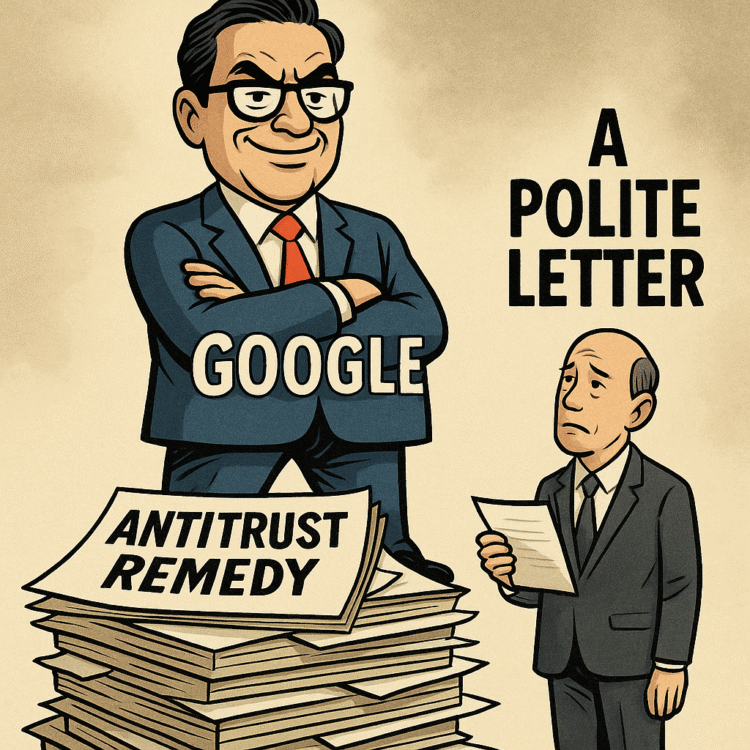

Letters, Not Laws

What Judge Mehta’s order proves, once again, is that America doesn’t regulate tech. It lectures tech. It writes long, careful letters filled with caveats and exceptions. It asks politely for cooperation. It crafts oversight regimes that expire before the ink is dry.

The platforms, meanwhile, move faster. They interpret, delay, comply selectively. They adapt not by changing behavior, but by changing definitions. “Exclusive” becomes “non-exclusive with conditions.” “Sharing” becomes “limited access to a curated subset.” Every regulation becomes a marketing opportunity.

Antitrust as Performance Art

What we witnessed on September 2 was not antitrust enforcement. It was antitrust theater. A carefully scripted act in which the government plays tough, the judge plays balanced, the platforms play along, and the public plays the fool.

Google will issue statements about how seriously it takes its obligations. Rivals will issue cautious optimism while knowing the crumbs won’t make bread. Regulators will issue press releases boasting of their historic win. And users will keep typing their queries into the same box, served the same ads, fed the same defaults.

The monopoly remains. The show must go on.

The Haunting Close

Two-hundred and twenty-six pages later, what do we have? A decree that bans exclusivity but preserves dominance. A mandate to share data that won’t level the field. Five years of oversight that expires before the ink dries. Markets that cheer continuity. Advocates that fume futility.

It is America’s antitrust story in miniature: polite letters to empires that laugh in daylight.

The haunting truth is this: monopoly power doesn’t crumble under the weight of PDF rulings. It adapts, absorbs, and metastasizes. By the time the decree sunsets in 2030, Google will be even larger, even richer, even more entrenched. The defaults will still default, the ads will still flood, the rivals will still starve.

And when the next judge takes the bench, America will once again ask: will we finally police platform power—or just write it another polite letter?