Somewhere between your tenth doomscroll of the morning and your third attempt to remember which war we’re supposed to care about this week, PBS quietly aired the most important documentary of the decade — Raoul Peck’s Orwell: 2+2=5 — and almost no one noticed, because there wasn’t a trailer trending on TikTok. It’s a film about how truth has become a boutique subscription service, curated by algorithms and sponsored by defense contractors. Peck, who once resurrected James Baldwin to narrate America’s racial neurosis, has now exhumed George Orwell to do the same for our epistemological one. If I Am Not Your Negro was a mirror, 2+2=5 is a math test, and we’re all failing it spectacularly.

The Documentary About Reality That Feels Unreal

Peck’s documentary is devastatingly simple in its structure, but harrowing in its message. He lets Orwell speak for himself, narrating a present that has stopped pretending it’s not dystopian. Archival footage bleeds into drone shots and digital billboards, blending mid-century fascist rallies with modern influencer culture so seamlessly you stop being able to tell which is which. There are no pundits, no talking heads, and no smug narration to soften the blow. Just Orwell’s voice — precise, weary, unflinching — describing a world where language has been weaponized, and the battlefield is your own brain.

You might think Orwell’s warnings about propaganda and truth-decay have been overused, but Peck doesn’t recycle them. He reanimates them. He drags the viewer, blinking and scrolling, through the digital dystopia we built from Orwell’s discarded blueprints. We see the glowing sprawl of China’s social credit system, the fluorescent branding of Silicon Valley, the algorithmic propaganda loops of American cable news, and the book bans of Florida. Different architects, same blueprint. The geography changes, but the control looks familiar.

The Ministry of Public Relations

If Orwell imagined a Ministry of Truth, we’ve since upgraded to a Ministry of Public Relations — a global joint venture between governments, corporations, and whatever’s left of your attention span. The film makes clear that the new authoritarianism doesn’t require gulags or guards; it just needs push notifications. Our national pastime isn’t baseball anymore, it’s plausible deniability.

Peck cuts between mid-century propaganda reels and modern political ads, showing how propaganda has evolved from grainy film reels to sponsored posts. The slogans haven’t changed much, but the medium has gotten better at hiding itself. The new orthodoxy scrolls by in high definition: War is Peace. Freedom is Security. Privacy is Suspicious Behavior. Please Accept Cookies to Continue. Orwell’s world was about control through fear; ours is about control through convenience. We’ll hand over anything, as long as the app loads fast.

The Algorithm Decides What You Know

In Orwell’s time, propaganda required effort — posters, censors, secret police. Now it just needs Wi-Fi. Peck doesn’t say it outright, but the message is obvious: Big Brother didn’t need to watch us; he just needed to build a platform that makes us watch ourselves. We installed telescreens in our pockets, we let them track our heartbeats, and we called it “wellness.”

The brilliance of modern control is that it’s invisible. It’s privatized, gamified, and user-friendly. You don’t need to imprison people if you can simply drown them in contradictory information until they stop trying to discern what’s real. Somewhere in a clean office in Palo Alto, an engineer with stock options tweaks the code that decides which version of the world you see. We used to worry about censorship; now we have personalization.

The Book Burning App

Peck’s montage of modern censorship hits hardest. Parents scream at school boards. Politicians wave banned books like trophies. Entire novels are turned into hashtags and removed from school libraries while corporations pretend neutrality. Once upon a time, tyrants had to burn books to suppress ideas. Now we just shadowban them. It’s faster, cleaner, and more efficient.

The cultural right bans The Handmaid’s Tale for being too feminist, the cultural left cancels 1984 for being too male, and Amazon quietly adjusts search results so no one notices either way. We no longer need to censor dissent when distraction does the job for free. “Community guidelines” are the new chains, and we’re the ones tightening them. Peck shows this not as parody, but as tragedy.

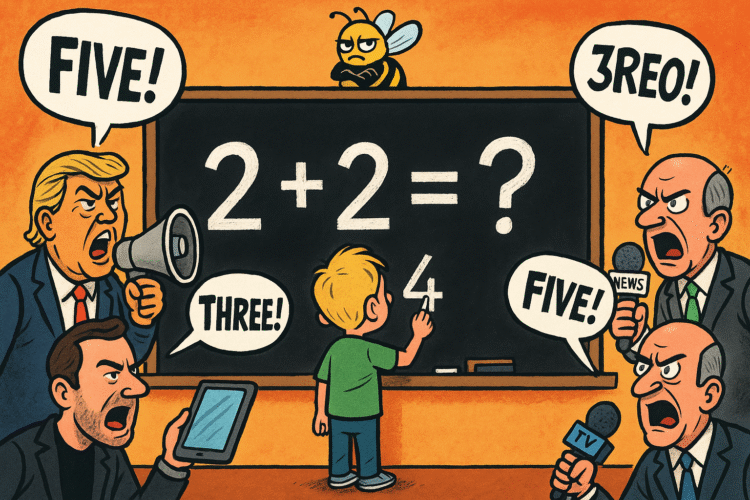

Two Plus Two Equals Engagement

When Orwell wrote that “freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four,” he probably didn’t imagine a future where that statement would be flagged for “context.” Today, two plus two equals whatever gets the highest engagement rate. Truth has been replaced by virality, sincerity by reach, and accuracy by emotional resonance.

Peck overlays Orwell’s text with footage of news pundits and influencers shouting into the void, all selling versions of reality to audiences that crave validation more than truth. If you can convince enough people that five feels true, you don’t need four to exist. This is how we get conspiracy theorists with microphones, elected officials with delusions, and citizens who can’t tell the difference between an editorial and a psyop. Two plus two equals five because five trends better.

The Content-Industrial Complex

Peck’s diagnosis is that the real villain isn’t ideology — it’s the attention economy. Governments learned propaganda from advertisers; advertisers learned it from governments. Now everyone’s fluent. Every headline is a product, every reaction monetized, every human emotion run through an algorithm that determines whether it’s profitable enough to amplify.

The film juxtaposes Orwell’s prose about “doublethink” with split-screen montages of cable news, influencer streams, and viral outrage clips, each demanding belief and disbelief simultaneously. It’s not censorship that destroys the mind — it’s noise. We live in the Content-Industrial Complex, where everything is propaganda because nothing is sacred. Engagement, as Orwell might say, is power pretending to be participation.

The United States of Amnesia

The film’s global montage eventually lands in America, and the effect is chilling. Surveillance in Beijing looks just like traffic cameras in New York. Riot police in Tehran mirror federal agents in Portland. Propaganda billboards in Moscow resemble Texas school board meetings. The point is clear: authoritarianism doesn’t wear uniforms anymore; it wears branding.

Peck lets the images linger until the viewer feels something close to shame. We don’t need force to suppress dissent — we have fatigue. We live in a country where being informed feels exhausting, so we’ve rebranded ignorance as self-care. We scroll past state violence, share the meme version, and move on. Our attention spans have been colonized, and our moral outrage outsourced.

Corporate Empires and Digital Peasants

In one of the most visually biting sequences, Peck frames Orwell’s Ministries as modern corporations. The Ministry of Truth is now Google. The Ministry of Love is Meta. The Ministry of Plenty is Amazon. It’s not dystopia by decree; it’s dystopia by delivery truck.

We’re no longer governed — we’re subscribed. Peck’s narration drips with irony as he contrasts Orwell’s gray bureaucrats with sleek CEOs in designer hoodies. Big Brother didn’t seize the means of production; he bought them on credit and added two-day shipping. The result is a population of digital peasants worshipping their overlords for the privilege of being surveilled in high definition.

Doubt as a Service

Peck devotes an entire section to the professionalization of uncertainty. He shows the sprawling network of think tanks, PR firms, lobbyists, and fake experts whose sole purpose is to inject confusion into the bloodstream of democracy. When you can’t trust anyone, you’ll believe anything — and that’s the point.

The documentary plays clips of politicians contradicting themselves mid-sentence, of pundits spinning outrage into ratings, of scientists being undermined by influencers with ring lights. It’s absurd, but it’s deadly. A society that treats facts as partisan accessories cannot survive itself. Hannah Arendt once said totalitarianism thrives when people lose faith in shared reality. In 2025, we call that the algorithm.

The Freedom to Be Told

Brangham’s PBS segment summarizes Peck’s warning in a single brutal line: the right to know has been replaced by the right to be told. We no longer demand truth; we expect service. Facts are treated like fast food — prepackaged, processed, delivered instantly, and consumed without thought. We’ve turned intellectual independence into a convenience issue.

Language itself is being stripped for parts. Peck’s footage shows corporate slogans and government euphemisms as interchangeable: “enhanced interrogation,” “content moderation,” “community safety.” Each phrase a verbal laundering of brutality. We’re living in a country that treats euphemism as governance and confusion as patriotism.

Peck’s Choice: No Heroes, No Villains

Unlike most documentaries, 2+2=5 refuses to give us heroes. There’s no savior journalist or viral activist montage. Just ordinary people scrolling through history, numbly aware that something is off but too tired to care. Peck doesn’t offer catharsis, because there isn’t any. The film is a mirror that asks a terrible question: what if the dystopia doesn’t need our consent — only our distraction?

He doesn’t frame it as apocalypse but as entropy. Not an explosion, but a slow pixelation of reality. Freedom isn’t taken all at once; it’s absorbed, repackaged, and sold back to you as premium access.

Propaganda as Weather

Halfway through the film, Peck layers Orwell’s words over a collage of Times Square billboards, influencer feeds, and news broadcasts until everything becomes indistinguishable static. Propaganda, he suggests, isn’t an event anymore. It’s atmospheric. It’s the background radiation of modern life.

We’ve built a climate of manipulation so total that we mistake its temperature for normalcy. When outrage becomes constant, it stops feeling like injustice. It feels like air. And like pollution, it kills slowly — invisibly, quietly, efficiently.

The Cult of Certainty

Peck’s portrayal of the modern mind is cruelly accurate. We no longer seek truth; we seek affirmation. Every opinion is a performance. Every conversation a loyalty test. We curate our identities like storefronts, terrified that an inconsistent belief might tank our brand.

“Tell your truth,” we say, not realizing that we’ve privatized the concept of truth itself. Facts are now personal property. Debate is theater. Our public discourse is a shouting match between people who all insist they’re being silenced. The more we talk, the less we mean.

When Dystopia Feels Like Nostalgia

By the end, Peck has done something Orwell never could: he’s made dystopia nostalgic. We look at those black-and-white newsreels of totalitarian parades and think, At least they looked organized. Our dystopia is disorganized, crowdsourced, and accidentally hilarious. We meme our own decay, we remix our own repression, and we call it content.

Peck’s closing montage plays like a requiem for seriousness. Drones, data farms, book bans, influencers — all blurring into a single grotesque ballet of distraction. It’s not that we’re being lied to; it’s that we’ve stopped minding.

The Most Radical Act

In the film’s quietest moment, Orwell’s voice says, “In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Peck shows a child writing 2 + 2 = 4 on a chalkboard. The camera lingers. The chalk breaks. It shouldn’t be emotional, but it is. Because in a world where everything is spin, arithmetic feels like defiance.

Peck doesn’t ask you to riot; he asks you to remember math. Truth, he suggests, isn’t heroic — it’s stubborn. It’s mundane. It’s the one thing that refuses to trend.

The Math of Silence

When the film fades to black, Peck leaves us with a whisper from Orwell: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” It’s a bleak sort of hope — not triumphant, but defiant. The hum of servers fills the silence, and you realize that’s us: the constant, restless buzz of a civilization that confuses noise for proof of life.

The danger isn’t that someone will force us to say two plus two equals five. It’s that, one day, we’ll stop caring what it equals at all. The arithmetic will still exist, quietly, unchanging, waiting for someone — anyone — to notice.

The film isn’t prophecy. It’s inventory. And if Peck’s right, the ledger is almost full.