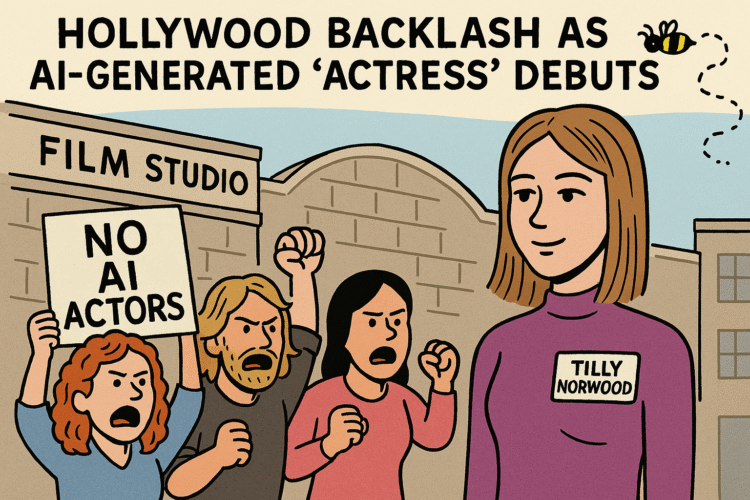

In a moment that could only have been written by the algorithms, a Dutch producer named Eline Van der Velden unveiled Tilly Norwood—the first AI-generated “actress”—at the Zurich Film Festival’s Zurich Summit. She was introduced as the future of filmed performance: fully animated, agency-ready, cost-efficient (up to 90 % cheaper than a human), and free from the whims of scheduling, diet, or agent demands. Within hours, the industry erupted. SAG-AFTRA issued a blistering condemnation. Big actors threw down gauntlets: “Don’t rep it.” Trades scrambled to explain why acting is more than a neural net. Tilly Norwood, bless her synthetic heart, began posting images of herself on social media, courting representation with curated smiles.

This backlash is not just about one digital face. It’s the fight over whether AI characters can be packaged and sold as “talent” or must remain tools—effects, not actors. It is a labor war in the code. Let’s trace how we got here—and why Hollywood’s fury just might decide whether stories remain human.

The Timeline of Outrage

- Zurich Summit, September 27, 2025: Van der Velden steps onto the stage and introduces Tilly Norwood. She touts cost savings (up to 90 %), always-on availability, and the business logic of synthetic talent. She says she’s already in talks with agencies and that Norwood could fill roles from background work to commercials to major features. The crowd shifts in their seats. Cameras flash. Futures are being auctioned.

- September 29–30: Hollywood awakens to the announcement. Trades run speculative think pieces: “Will Tilly Star in Next Blockbuster?” Network morning shows raise the question: Is AI acting coming for real actors? Agents murmur. Clubs convene. On Instagram, Tilly posts a sleek portrait with the caption: “Ready for my close-up. DM your agencies.”

- Union Statements: SAG-AFTRA releases: a synthetic performer is not an actor. It has no rights. It can’t bargain. It was trained on unlicensed performances. It’s an existential threat to contracts demanding notice, consent, bargaining over use—and compensation. The performers’ guild asserts that any agency who “rep” Tilly is breaching its duty to human clients.

- Actors Push Back: Voices rise. Emily Blunt says it’s a betrayal of craft. Natasha Lyonne warns that synthetic voices won’t feel real but will kill real opportunity. Melissa Barrera calls it exploitation in algorithmic form. Agencies hear rumblings of “do-not-rep” lists: agents who sign Tilly risk losing human clients.

- Trade & News Coverage: Entertainment trades run lines: “Uncanny valley meets union valley.” Morning talk shows debate AI characters. Network segments show side-by-side comparisons of synthetic Tilly vs. a human actor, asking audiences whether they can spot the difference. The public awakens to a new battleground: flesh vs. code.

The Players & Their Claims

Van der Velden & the AI Tool Defense

Van der Velden insists Tilly is a creative tool, not a replacement for human actors. She argues that many visual effects, digital doubles, de-aged faces, stunt doubles already exist in film. Tilly is just the next iteration: scalable, efficient, controllable. She frames it as innovation, not displacement. Yes, agencies would rep her—but as a novel asset. Yes, she says, the training data is carefully licensed—or so she claims—and synthetic modeling is only as ethical as the data behind it. She invites conversations about fair use, attribution, shared revenue, and algorithmic transparency.

This tool defense, however, is slippery. If an AI “actress” can deliver lines, emotive nuance, lip-synch, recite dialogues in scenes, then at what point is she no longer a tool but a performer? Van der Velden tries to have it both ways: human-like enough to cast, but algorithmic enough to disown responsibility.

Guilds, Contracts & Legal Protections

SAG-AFTRA and other guilds point to recent strikes (2023–24) where language on AI likeness, training data rights, notice, and compensation entered collective bargaining. They argue synthetic performers should trigger the same contract rules: notice to human actors, possibility of negotiation on usage, royalties, attribution rights. They want audits of the training datasets. They want forced disclosure: If you use AI, you must reveal how it was trained, which human performances contributed, and who had consent.

The guilds also propose contract enforcement triggers: any studio or agency that signs Tilly triggers mandatory penalties, as though they used an uncredited body double without permission. And if a client’s likeness was part of the training data (voice, face, movement), those actors have a right to compensation or veto. They see Tilly not as art, but as a potential breach of intellectual property, contract, and labor frameworks all at once.

Stakes in Hollywood’s Ecosystem

- Agency defection / “Do Not Rep” Lists: Agents may face losing human clients if they represent Tilly. Agencies must choose whether to be early adopters or be blacklisted by talent.

- Contract enforcement: Will synthetic performers trigger minimums, residual pay, credit obligations, background/extra contracts, insurance, bonding? Studios may try to label Tilly as “effects,” paying lower rates, removing overhead. But human performers may demand parity.

- Training data audits: Studios could be forced to open toolboxes and reveal which actor clips trained motion or voice models. That could expose unauthorized use or “scraping” of performances. Litigation is imminent: actors whose work was used without consent may sue.

- Consent / pay for trained performances: If an AI performance leverages a composite of many actors’ voices or gestures, those human contributors often won’t know or be compensated. This raises ethical rupture: labor replaced without consent.

- Downstream effects: Extras, background actors, ADR (dubbing), stunt performers—all vulnerable. With Tilly, a studio might opt to fill crowd scenes with synthetic faces. Indie budgets might lean toward AI “talent” over real actors to save costs. Streamers might flood content with AI banking to boost return on investment—the volume model now becomes synthetic churn.

The Core Test: Actor or Algorithm?

This is not just a fight over a single synthetic face. It’s a test: can an algorithm be the “actor,” or must it always remain an effect? If Tilly is recognized legally, contractually, rating-box-office-wise as “talent,” then a tow-truck of consequences rolls onto the lot. Insurance policies may refuse to underwrite AI performers, bonds for production may be questioned, crediting systems break down (who gets “performed by Tilly, compiled from A, B, C” credits?). Audiences may reject synthetic faces—or accept them. This moment forces the industry to decide: Is performance a human act, or a series of data interpolations?

What Makes It Satirical—and Devastating

The joke is that Hollywood, which used to employ hundreds of ghostwriters, digital doubles, de-agencies, stunt doubles—all while calling them invisible labor—now pretends synthetic actors are “too radical.” They used to praise CGI de-aging, virtual extras, digital voice dubbing. But when the code becomes the actor, they recoil. The satire lies in how they embraced digital trickery until that trickery demanded royalties, labor rights, and contract negotiation.

Van der Velden’s pitch about 90 % cost savings is a punchline in advance: the moment studios cut human pay by 90 % is when the labor fight becomes existential. The idea of her courted by agencies while real people beg for bookings is like a cruel math joke.

Actors protesting “lived experience, emotion, embodiment”—those are real human truths. AI can approximate, but it cannot bleed or struggle or audition with nerves. Yet they sell us the illusion of equivalence at margins.

Final Thought

Tilly Norwood may be synthetic, but the fight is deeply human. This backlash is not nostalgia. It is desperate defense of dignity. The crux is not whether we ban AI, but whether we fence it, regulate it, make it transparent, accountable, respectful of labor, and constrained in power. If synthetic characters become full “talent,” then we risk entire industries converted into algorithms—or replaced wholesale.

Artists are not extinct. They are not APIs. No algorithm can replace the crises, failures, heartbeat, improvisations that make performance human. If Tilly becomes a “star,” then we live in a future where creativity is downloadable, emotion is synthetic, and the human in art is optional.

But in that future, what claims will the humans have left? If an AI can play roles, then the fight is over the contracts, the gates, the rights, the pay—not the performance. And that fight is Hollywood’s moment now.

Let them rage. Let them litigate. This is not mere technophobia. This is the line before art is swallowed by code—before the actor becomes a script, not a soul.