Somewhere in Washington, a team of political appointees has decided that what the Smithsonian really needs — after two centuries of collecting and preserving the nation’s cultural heritage — is a more aggressive review of its exhibits. Yes, the Trump administration has announced that eight Smithsonian museums will now have their exhibition text, curation, and collections examined through the ever-clarifying lens of ideological purity.

Apparently, America’s premier museums have been getting history wrong this whole time, and only now, thanks to the sharp eyes of political operatives, will we learn the truth. Which is, coincidentally, whatever version of events polls best with voters who think the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1492.

The Political Takeover of the Guided Tour

Imagine this: you walk into the National Museum of American History and head toward the exhibit on the Civil Rights Movement. But before you can even get to Rosa Parks’ bus, you’re stopped by a cheerful staffer with a clipboard.

“Hi there! Just so you know, we’ve made a few updates to better reflect both sides of history.”

What follows is a guided tour rewritten as if it were a stump speech, with timelines rearranged for narrative convenience and historical villains rebranded as “early influencers.” It’s like Hamilton, but if Aaron Burr had a PAC and a podcast.

The New Exhibit Labels Practically Write Themselves

- The Dust Bowl — “A Great Opportunity for Soil Diversity.”

- The Trail of Tears — “America’s First Cross-Country Relocation Program.”

- The Civil War — “A Conflict Between Two Equally Valid Perspectives.”

Why stop there? Imagine the natural history museum redoing its dinosaur exhibit to reflect fossil denialism. T. rex becomes “Big Lizard, Probably a Hoax.” The meteor that wiped out the Cretaceous period is labeled “Climate Change Allegedly.”

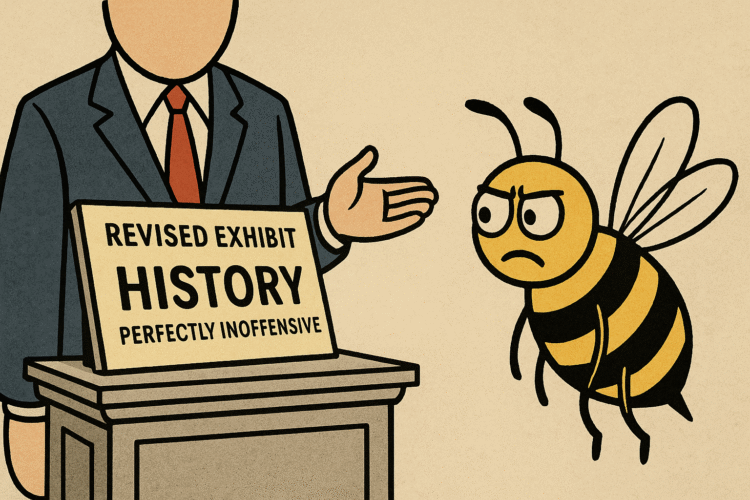

History With the Edges Sanded Off

Aggressive reviews sound bureaucratic, but they’re a political scalpel. The idea isn’t to burn the museum down — it’s to quietly rearrange the furniture so visitors start leaving with a slightly different impression. A more patriotic impression. The kind of impression where you might glance at the exhibit on Japanese-American internment camps and think, “Well, that seems… efficient.”

The review process, we’re told, will focus on balance. But “balance” in this context is like putting a flat-earther on NASA’s advisory board — it sounds fair until you realize one side has a spaceship and the other has a YouTube channel.

Why Museums Are Always the First to Go

Authoritarian-leaning governments have a long history of curating history to suit the moment. Libraries, archives, and museums are prime targets because they deal in memory — and memory is dangerous if left unregulated. It’s much easier to convince people the past was perfect if you get to decide what parts of it they see.

The Smithsonian is especially symbolic. It’s not just a set of buildings; it’s the country’s attic. It’s where we put the Wright brothers’ plane, Lincoln’s top hat, and Dorothy’s ruby slippers. If you can reframe those objects, you can reframe the story they tell.

The Trump Era Version of a School Field Trip

Picture a class of eighth graders visiting the National Air and Space Museum under the new review guidelines. They stop at the Apollo 11 module. The teacher explains that America put a man on the moon in 1969. A new sign at the exhibit gently adds: “Some experts dispute whether this event occurred as described. Ask your parents if you can watch our exclusive documentary: ‘One Giant Hoax for Mankind.’”

At the American Indian Museum, the tone shifts from genocide to “early land-sharing agreements.” The Museum of Natural History trades Darwin for “Intelligent Design Corner,” where an animatronic Ben Carson explains how the pyramids were actually used to store grain.

The Erasure Is the Point

This isn’t about accuracy. It’s about loyalty. Museums, by their nature, present facts that may be uncomfortable. But the goal of these “reviews” is to replace discomfort with pride — and not the kind of pride that comes from facing your history honestly, but the kind that comes from telling yourself bedtime stories.

If an exhibit on slavery makes you uneasy, the problem isn’t slavery — it’s the exhibit. If the section on McCarthyism feels a little too familiar, maybe it’s time to cut it down to a paragraph and add a note about “the dangers of communism.”

The Curation of Feelings

What’s fascinating here is that the administration isn’t just curating history — it’s curating emotional response. Museums won’t just teach you what happened; they’ll teach you how to feel about it. That’s why the review focuses on exhibition text. Objects are neutral until someone tells you their story.

A dress worn by a suffragette is inspiring when described as “symbol of a movement that changed America.” Change the label to “garment worn by activist involved in controversial protests” and suddenly it feels like she blocked traffic on your way to work.

The Eight Targets

Eight museums are under the microscope. Eight places where our national narrative is stored and shared. Eight opportunities to rewrite the margins and edit the captions until the past lines up perfectly with the present administration’s self-image.

And if you think this ends with eight, you’ve misunderstood the game. Once you’ve established the precedent that political review is not only acceptable but necessary, the list will grow. The Library of Congress. The National Archives. Eventually, your high school history textbook.

The Gift Shop Revolution

Even the gift shops aren’t safe. Imagine walking into the National Museum of African American History and Culture and finding a “Both Sides” coffee mug next to the Harriet Tubman posters. Or the Air and Space Museum selling moon landing skepticism starter kits.

This isn’t paranoia; it’s branding. Museums know their influence extends beyond the exhibit floor. Change the narrative, and you change the merch. Change the merch, and you change what people take home.

The Slow Boil

The real danger isn’t an immediate overhaul — it’s the slow, almost imperceptible shifting of the frame. Most visitors won’t notice a word removed here, a phrase softened there. But over time, the cumulative effect is a history that’s been politely declawed.

We’ll still have museums. We’ll still have artifacts. But we’ll have lost the rawness, the contradiction, the uncomfortable truth-telling that makes them vital. What’s left will be a scrapbook, not a record.

The Final Exhibit

Maybe one day, years from now, there will be an exhibit about this moment. It will feature press releases about “aggressive reviews,” news clippings about political interference, and maybe — if the curators are feeling bold — a case labeled “Democracy, in Decline.”

Visitors will walk past it on their way to the dinosaur hall, and a child will tug on their parent’s sleeve: “Why would they want to change history?”

And the parent will pause, searching for the right words, before answering: “Because they thought it would make the future easier to control.”