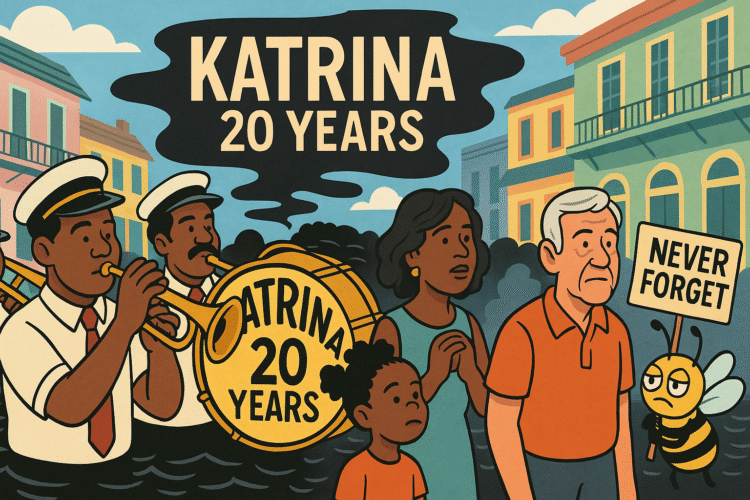

Twenty years later, America still doesn’t know how to talk about Hurricane Katrina. Not because there’s nothing left to say, but because the event itself was already so saturated in meaning that everything since feels like a remix. The anniversary observances in New Orleans this August were equal parts solemnity and stagecraft—brass-band second lines echoing grief and resilience, memorial services beneath flood-stained walls, educational programs about infrastructure wrapped in PR gloss, chefs curating the language of “resilience” onto tasting menus. It was both a city remembering and a nation rehearsing.

You could watch the ceremonies and feel moved—genuinely, deeply moved. And you could also feel the cynicism creeping in: the uneasy sense that even tragedy ages into brand management, that “Katrina at 20” has become a commemorative hashtag sandwiched between Barbie sequel promotions and a Supreme Court leak. America loves anniversaries. They allow us to package grief into programming blocks, balance resilience against trauma, and promise that “this time” we’ve learned.

The memorials themselves carried a kind of double vision. The brass bands, the parades, the music—these are the truest expressions of New Orleans: joy braided with pain, defiance alongside mourning. They carry the weight of cultural endurance, the reminder that the city was never merely buildings and levees but a sound, a rhythm, a ritual of survival. Yet behind every second line beat, you could also hear the quiet whisper of gentrification: the neighborhoods rebuilt into Airbnbs, the culture commodified for visitors, the same music piped into luxury hotel lobbies where Katrina survivors could never afford to stay.

The lesson, if there is one, is that cultural memory is resilient. The question is who gets to profit from it.

The environment was framed as a scientific epilogue. Louisiana officials pointed to the 67,000 acres of wetlands restored and the 71 miles of protective barriers built under the Coastal Master Plan. The talking points were familiar: if we rebuild nature, nature will protect us. Wetlands as levees, marshes as shields. And yet, as reporters noted, even as the ribbon-cutting continues, major projects like the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion have been quietly scrapped. Progress, but partial. Effort, but eroding.

There’s a bitter irony in celebrating 67,000 acres restored when losses since Katrina exceed half a million. It’s like watching your house burn down, salvaging a chair from the ashes, and congratulating yourself on “home improvement.” Officials framed it as resilience. Residents know it as triage.

Katrina also changed the food scene, because of course it did. When you devastate a city, you devastate its kitchens. Chefs were forced into improvisation, remaking menus from whatever was available, channeling scarcity into innovation. Out of that trauma came what industry writers now call a “forced reset”—a culinary renaissance that introduced global flavors, broadened the city’s palate, and diversified who gets to cook professionally.

It’s the kind of story that makes food magazines salivate: tragedy as prelude to creativity, disaster birthing a better gumbo. But beneath the glossy essays, you hear the quieter truth: people cooked differently because they had no choice. Restaurants shifted because supply chains collapsed. Innovation was survival, not strategy. The celebration of “culinary resilience” often forgets that many kitchens never reopened, many chefs never returned, and many families never got their kitchens back at all.

Survivor stories remain the most haunting. Charmaine Neville, musician and member of New Orleans royalty, has long told her Katrina tale. Stranded by floodwaters, threatened by violence, even facing alligators in the rising waters, she turned her ordeal into survival for others—rescuing, helping, testifying. Her life is proof that resilience is not an abstract noun; it’s muscle memory, it’s panic transmuted into action.

But every retelling also reminds us that the city didn’t flood because of a storm. It flooded because levees failed. Because planning failed. Because leadership failed. Katrina was a natural disaster compounded into a social massacre. Neville’s story is not just one of survival—it’s an indictment.

The ghost of FEMA still looms. For the 20th anniversary, more than 180 current and former FEMA employees signed a “Katrina Declaration,” warning that the same forces that left the Gulf Coast abandoned in 2005 are back at the helm. Political meddling. Budget cuts. Personnel attrition. They pointed to the recent deadly Texas floods as evidence that preparedness is unraveling again, that FEMA remains fragile, that the reforms we swore would never be undone have quietly been unraveled.

There is something bleakly comic about FEMA officials issuing warnings in 2025 that could have been copy-pasted from 2005. Two decades of “never again” reduced to “maybe tomorrow.” The call to restore FEMA’s cabinet-level authority felt less like policy advocacy and more like a desperate plea not to be sidelined the next time bodies float down American streets.

The militarization of disaster response, too, has returned to the conversation. Katrina was remembered not only for its destruction but for the sight of National Guard troops with rifles patrolling streets where food and water were still missing. The 20th anniversary invited comparisons to more recent crises—where military optics often substitute for human-centered relief. Commentators pointed to Lt. Gen. Russell Honoré’s Katrina-era leadership, which shifted response away from combat mode and toward rescue. His name now floats like a relic of what could have been: the reminder that you don’t need to point rifles at the drowned.

The satire writes itself: America still confuses aid with occupation, as if sandbags were insurgents and flooded schools needed checkpoints. Every disaster risks becoming a security exercise first, a humanitarian effort second. Katrina taught us this. We’re still learning.

Beneath all the ceremony, the broader themes refuse to fade. Race and poverty shaped who died, who lived, who returned, and who was forgotten. Katrina made that undeniable, but the denial crept back anyway. The anniversaries rehearse inequality as if repetition could dilute it: “Yes, we know Black residents bore the brunt, yes, we know poor residents were stranded, yes, yes, yes—but look at our upgraded levees.” The subtext is always the same: acknowledgment without redistribution.

Infrastructure is still fragile, policies still brittle. Billions were spent upgrading levees, but concerns linger: design flaws, underinvestment, political meddling. Even now, experts warn that the very safeguards we hailed as unbreachable are being neglected. America loves to build walls and loves even more to underfund their maintenance. Twenty years after the most visible failure of public infrastructure in living memory, the lesson is still in jeopardy of being forgotten.

What Katrina also left is cultural memory as mobilizing force. Survivors tell stories. Musicians write songs. Chefs feed resilience onto plates. Educators build programs to remember. The city refuses to forget, even if the nation is more comfortable with selective amnesia.

And then there is media. Documentaries, testimonials, anniversary specials. The retelling itself has become its own industry. Narrative memory keeps accountability alive, or at least attempts to. Without it, anniversaries become pageantry. With it, anniversaries become warning signs. The line between the two is perilously thin.

So what do we do with Katrina at 20? The safe answer is to praise the resilience of New Orleans, to admire the rebuilt neighborhoods, to applaud the memorial parades, to quote Neville’s survival, to cite FEMA’s declaration, to nod at wetlands restoration. That’s the answer you’ll see in op-eds and press releases.

The harder answer is to admit that twenty years later, Katrina remains less a past event than a permanent condition: a case study of what happens when inequality, neglect, and hubris converge. The levees broke once. The trust in institutions broke permanently. Every anniversary since has been an act of damage control—not just of memory, but of accountability.

The brass bands will march. The wetlands will be rebuilt, then eroded again. FEMA will issue more declarations. Survivors will tell their stories until voices give out. And the rest of America will watch from a distance, moved by the spectacle, absolved by the narrative, unbothered by the repetition.

The haunting truth is this: Katrina never ended. It lingers, disguised as an anniversary. The storm passed. The neglect stayed.