Regime change, now with a press release and an IOU.

On January 3, 2026, the United States woke up to a sentence that used to require months of debate, a roll call vote, and at least the pretense of international consensus. President Donald Trump announced that the U.S. military had executed a “large-scale strike” on Caracas, captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores in a covert operation, and removed them from the country. They were flown to New York to face federal narcotics and narco-terrorism charges. Washington, Trump said, would “run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition.” He also left the door open to future ground forces if necessary, the kind of phrase that always sounds temporary until it isn’t.

That is not how coups are supposed to be described anymore. They usually arrive with euphemisms, with phrases like “supporting democratic aspirations” or “assisting a transition.” This one arrived with a timetable that started at now and ended at whenever the United States decides it’s done.

The operation did not fall out of the sky. It was the loud punctuation at the end of months of escalation that had already stretched legal boundaries thin. Maritime strikes on alleged drug smugglers. Seizures of sanctioned oil tankers off Venezuela’s coast. Drone activity and intelligence operations aimed at trafficking facilities and regime finances. A rhetorical shift that fused the “war on cartels” language with Venezuela itself, turning a country into a target set. By January, the administration had stopped pretending this was only about interdiction and started speaking openly about removal.

When the announcement came, it landed like a crash test for every norm the United States claims to value.

Trump’s declaration framed the strike as decisive and necessary. Maduro’s capture was presented as a victory against narco-terrorism. The transfer to New York was framed as justice. The promise to administer the country was framed as responsibility. And the hint of ground forces was framed as prudence. It was a full menu, served quickly, with no visible check for who ordered what and under whose authority.

To understand why January 3 matters, you have to separate spectacle from structure.

The spectacle was dramatic. Helicopters. Precision. A capital city hit. A head of state in custody. A press conference tone that mixed triumph with casual menace. The structure is where the alarm bells live.

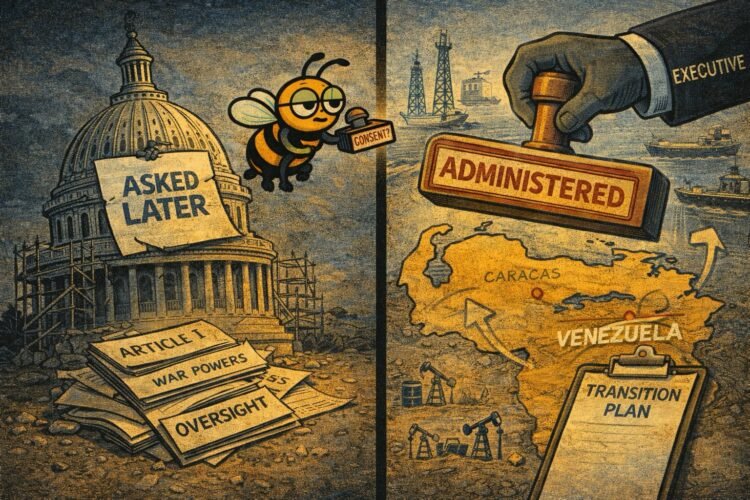

Under the U.S. Constitution, Article I gives Congress the power to declare war and authorize prolonged military operations abroad. That is not a decorative clause. It exists to prevent exactly this scenario, where one person can decide to use force to topple a government and then ask the legislature to applaud afterward. The president is the commander in chief, not the commander in everything. When operations move from discrete actions into regime change and occupation, the Constitution demands authorization.

There was none.

No declaration. No authorization for the use of military force tailored to regime change. No public vote. Lawmakers from both parties said they were not briefed on plans to remove Maduro, let alone to administer Venezuela’s political and oil infrastructure. Some Democrats said they were misled. Some Republicans expressed unease about open-ended commitments and the prospect of ground troops. That mix of reactions tells you everything you need to know about how much consent existed before the strike.

International law is even less forgiving. The United Nations Charter prohibits one state from using force to overthrow another’s government absent Security Council approval or a clear self-defense justification. Venezuela did not attack the United States. There was no imminent armed threat to U.S. territory that would meet the standard. Security Council approval was not sought, much less granted. Legal scholars called the operation an illegal coup and warned that it sets a precedent that erodes sovereign norms, especially in a region with a long memory of foreign intervention.

Those warnings were not abstract. Russia and China condemned the action and called for restraint and adherence to established legal frameworks. U.N. officials urged de-escalation and respect for sovereignty. Even allies who have no love for Maduro expressed concern about unilateral force and the implications for regional stability. You do not have to defend a dictator to oppose a doctrine that says power decides legitimacy.

Inside Venezuela, the reaction fractured along familiar lines. Some opposition figures celebrated Maduro’s removal, seeing a chance they had been denied for years. Some residents expressed relief, hope, even joy. That reaction is real and understandable. Authoritarian governments hollow out trust until any rupture feels like oxygen. But relief does not equal consent, and celebration does not solve the next problem, which is who decides what comes next.

Because Washington did not merely assist an internal transition. It declared itself the administrator.

Running another country is not a metaphor. It means deciding who controls ministries. It means deciding how oil flows, who signs contracts, who secures ports, who polices streets, who writes budgets. Venezuela is not an abstract moral project. It is a complex society with institutions, factions, debts, and a history of external exploitation. U.S. control over Venezuelan oil infrastructure immediately raised fears of economic extraction disguised as stabilization. When a foreign power says it will run a country and manage its most valuable resource, skepticism is not cynicism. It is pattern recognition.

The administration’s justification leaned heavily on narcotics charges. Maduro and Flores were presented as criminals, and criminals, the logic goes, can be arrested anywhere. This is where the argument slips from law into convenience. Indictments do not authorize invasion. Extradition is a process, not a raid. Turning criminal charges into a pretext for regime change collapses the line between law enforcement and war. It teaches the world that if the United States can charge you, it can remove you.

That lesson will not be lost on other governments.

The domestic political fallout arrived quickly. Democrats demanded oversight hearings and questioned whether the War Powers Resolution had been violated. Some Republicans praised the boldness while warning against quagmires. Others stayed quiet, which in Washington is often a sign of discomfort masquerading as strategy. Legal experts across the spectrum warned that bypassing Congress weakens democratic legitimacy and invites retaliation, not just abroad but at home, where executive power expands because it was not challenged.

The administration’s defenders argued necessity. They argued that months of pressure had failed, that sanctions and seizures were insufficient, that cartels and corruption demanded decisive action. They argued that the United States could not wait for process while drugs flowed and instability festered. They argued, in short, that urgency outruns law.

Urgency always does. That is why law exists.

There is also the hypocrisy problem, which refuses to stay buried. A foreign policy that cannot temporarily stabilize domestic challenges now claims the authority to govern a foreign state. The same government that struggles with infrastructure failures, healthcare instability, climate shocks, and political paralysis decided it had the bandwidth to run Venezuela. The same leaders who insist Congress is dysfunctional decided Congress was optional.

This is not just about Venezuela. It is about the kind of country the United States wants to be when power is available and restraint is inconvenient.

The months leading up to January 3 matter because they show the slow normalization of escalation. Drone strikes became routine. Intelligence operations blurred into military ones. Maritime seizures were framed as policing while carrying the risk of war. Rhetoric hardened. Venezuela was folded into a broader “America First” posture that treated the hemisphere as a chessboard and oil as a lever. Each step made the next one easier. By the time Caracas was hit, the idea had been rehearsed enough to feel inevitable.

Inevitability is a story leaders tell when they want to avoid accountability.

What is the exit strategy. That question has been asked so often in American history that it should be printed on briefing folders. The administration offered none. “Until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition” is not a plan. It is a promise to decide later. Hints of future ground forces are not reassurance. They are warnings.

Occupation, even when dressed up as administration, creates incentives that are hard to unwind. Local factions compete for favor. Resources become bargaining chips. Violence shifts shape. The occupying power becomes responsible for outcomes it cannot fully control. Every day without a clear end point increases the cost of leaving.

Supporters will say Venezuela is different. That this time the objective is narrow. That this time the removal of a corrupt leader will unlock stability. That this time the United States will resist temptation. History suggests otherwise. History suggests that when a powerful country decides it can manage another country’s destiny, the bill arrives later and it is never paid in optimism.

The moral argument is also thinner than advertised. Protecting people does not require ruling them. Supporting democracy does not require suspending it at home. Human rights are not strengthened by erasing due process and substituting force. If the goal were purely to stop repression, there were tools short of regime change that had not been exhausted. The leap to capture and control was a choice, not an inevitability.

There is a reason international law treats sovereignty as more than a suggestion. It exists to prevent the strong from deciding the fate of the weak based on interests dressed up as ethics. When that law is ignored, it does not disappear. It waits, and it returns in forms that are less predictable and more dangerous.

January 3 will be remembered not only for what happened in Caracas, but for what it revealed in Washington. It revealed a presidency comfortable with unilateral force. It revealed a legislature sidelined. It revealed a habit of conflating criminality with casus belli. It revealed an administration willing to administer another country without asking its own citizens for permission.

Some will call this leadership. Others will call it recklessness. Both sides will argue over results. But the deeper issue is precedent. If this stands, if Congress shrugs, if courts avert their eyes, then the United States has taught itself a new rule. That when the executive says “locked and loaded,” law follows, not leads.

That rule will not be applied only to enemies. It will shape how power is used everywhere.

For Venezuelans, the future is uncertain. For the region, the norms are shaken. For the United States, the mirror is unforgiving.