Glass Slippers, Half-Full and Holding

If you’ve been here long enough, you know I don’t birth a chapter into the world unless it’s been through at least one rewrite, one panic spiral, and one “maybe I’ll just fake my own death instead” moment. This one? It’s been rewritten five times. Five full passes of ripping it apart and sewing it back together until the seams don’t show but the scar tissue still does. And I’m proud—borderline evangelical—about what came out of that last round.

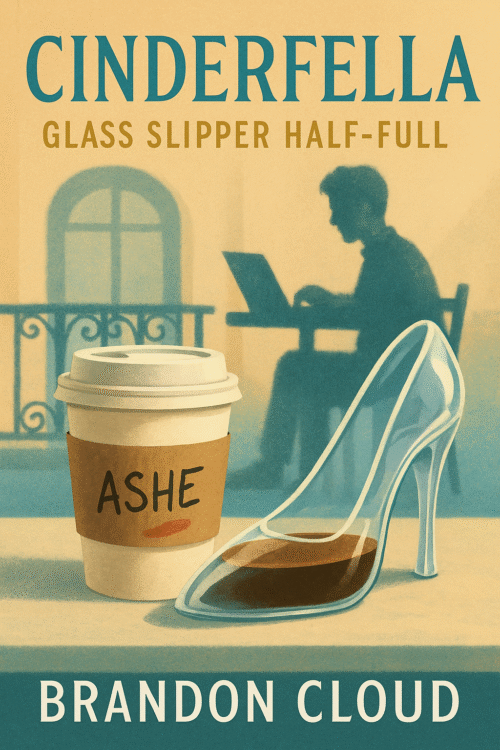

It belongs to Cinderfella: Glass Slipper Half-Full, the newest book in The Fairies Tell series—a fairy tale reimagining without the lace doilies or moral lessons, set in the queer humidity of 2025 New Orleans and the velveted chokehold of New York City. It’s a world where a cracked Doc Marten can be a plot device, a rhinestoned “fairy godfather” can pull you into a literary ball that feels more like a hostage negotiation, and love is something you recognize in the middle of your own mess—not after you’ve cleaned it up.

I write these books for people who’ve been told they have to pick between grit and magic, as if the two can’t cohabitate in the same skin. For people who’ve been mistaken for cynical when they’re actually just paying attention. For people who know that asking for what you need can feel like handing someone the knife and pointing to your ribs.

Asher, Ellis, Fay—they’re all carrying their own bruised mythologies into rooms where charm is currency and access comes with a receipt. The city squeezes, the parties seduce, and every question asked out loud is a little act of rebellion.

I’m sharing this chapter because it finally hits the exact frequency I’ve been chasing: part wry deflection, part bruised want, part heat-and-mildew claustrophobia, part velvet-and-glass performance. It’s the exact moment the story tilts, without announcing the tilt.

And tomorrow—or maybe later today if I can’t keep my hands off the “publish” button—the whole book will be out in the world. You’ll be able to find it, along with the rest of my 65+ emotionally intelligent, genre-bending queer books, on my Amazon author page.

The chapter is below. It’s got sweat and breath and the kind of dialogue where nobody really answers the question they were asked. It’s the one I’ll stand by even if the rest of the book gets banned in Florida.

Chapter 29

CONSENT BEFORE COMMAS

The chime is bubblegum; the work is scalpel. Asher clicks Join and straightens the cheap desk chair like posture could proofread. The camera opens on a face that knows when not to perform; Ellis’s window is lamp‑warm, a stack of legal pads framing him like good boundaries do. Don’t overthink the doorway. Walk in like the room already has your name on a chair.

“Timer?” Ellis asks, lifting a pen as if it were neutral ground. His voice arrives low, unhurried, the sound of someone carrying glass across tile. “We can do thirty on, five off. Or no clock at all.” The screen throws a tiny echo off the cursor; the blink keeps pace with his pulse instead of sprinting ahead.

“Clock it,” he says, dragging the doc into split view like he’s opening a ribcage carefully. “If I drift, I want daylight to catch me.” A grin tugs without auditions. “Please note, that was a metaphor, not consent for surgery.”

“Understood,” Ellis says, mouth curving without showing teeth. “Before we touch anything, contract out loud. Scope: I’ll propose cuts at the level of clause and sentence. I will not alter order, story, or voice without explicit invitation. Veto power: yours, always.” He taps the pen once, a metronome that stresses respect, not speed.

Asher nods and lets the nod be official. “Timelines?” he asks, aiming his irony at the ceiling so it won’t bite the person who doesn’t deserve it. “Because my landlord uses the moon to invoice.”

“Two slow passes in three weeks,” Ellis replies. “Then a shorter pass for continuity. ‘No’ means ‘not yet’ whenever you want it to. If feelings snag, we pause the doc and name the snag or we take a walk around a paragraph until air returns. I won’t argue you out of your own gut.” The last line lands with the weight of a door propped open by a brick that says HOME.

A calendar ping shivers the screen—Fay’s name dressed in all‑caps: PANEL CONFIRM + PRESS HOLD. Asher clicks the bell and sets the notification to later, as if postponing a parade could make it less shiny. “Publicity can sit,” he says, half to himself, half to the room they’re building. The silence that follows doesn’t accuse him of ingratitude; it just waits.

“Signals,” Ellis continues, unbothered. “If you want me to stop mid‑sentence, say ‘brake.’ If you want to move lanes—talk process instead of prose—say ‘switch.’ If you want more of something, I’ll ask ‘offer or ask’ to be clear.” He tilts the legal pad into frame like a waiter presenting a menu that isn’t a trap.

“Brake is tea,” Asher says, inevitably. “Because nothing sexy survives a kettle, and neither do bad edits.” He lines the laptop a finger’s width from the table edge, ritual dressed as ergonomics. You are allowed to be exact.

Ellis writes TEA on his pad in a square box. “Mine is red. One last clause,” he says, pen poised. “I’m not here to turn your lived thing into a smoother thing. I’m here to make the sentences hold without bribery. If something performs trauma for applause, I will flag it and then shut up unless you ask for more.”

“Sold,” Asher says. Relief arrives like cool air after a bus door opens, ordinary and necessary. “You can suggest, I can refuse, we can stop, the page doesn’t bleed if I change my mind.” He scrolls to the top and drags a sticky note onto the title page: Editorial consent governs this document. The motor in his wrist hums along, present and unremarkable.

Ellis clicks the timer into life. “We’re in,” he says. “Where would you like to begin?” The cursor blinks, patient as a nurse with good shoes. Start where you flinch.

He scrolls to the mid‑book paragraph that has avoided eye contact for months. The line sits there like an unpaid ticket: Asking is for people who can risk being told no in a way that won’t eat them. He reads aloud because air changes text, mouth shaping a sentence he wrote on a day when hunger and pride shared a shirt. The taste is metallic and honest.

“What does that line want?” Ellis asks, not moving in his square. No pitch about cutting, no sermon about shame needing verbs. Just room.

“It wants to be a hinge,” he says, thumbs resting on the spacebar like they could hold anything steady. “It wants to pivot the chapter from jokes to the thing under the jokes without turning the jokes into liars. It wants to admit the cost without cashing in on it.” The last clause lands and doesn’t apologize for the price of being specific.

“What does the paragraph want around it?” Ellis asks, pen tip hovering over paper like a hummingbird unsure of a flower. “You don’t owe me an answer. You can owe the line an answer if that’s useful.”

“It wants a witness that isn’t the room clapping,” he says before the old habits can drag on a cape. “So maybe we cut the pun after it. Or keep it and make the pun aim sideways, not upstage the hinge.” He highlights the joke about coupons he’d tucked in as a smoke bomb and watches it wilt.

“Offer: remove,” Ellis says, drawing a gentle line through a printout off‑camera. “Ask: do you want to test the paragraph with and without it—read both out loud—and decide by ear?”

“Offer accepted,” Asher says, clicking track changes like it owes him rent. He reads the stripped paragraph into the room, the hinge showing its clean face. The cursor winks; the doc breathes. It doesn’t collapse without the laugh; it straightens.

He tries the version with the joke, this time nudging the punch line so it refuses to steal attention. The laughter doesn’t ask for tips now; it steps aside. “Keep the adjusted one,” he says, surprising the small voice that likes binaries. “Not because it’s safer. Because it belongs.”

Ellis makes a small checkmark. “Note to self,” he says, half amuse, half archive. “When this book laughs, it doesn’t change the subject. It changes the temperature.” A pause opens and stays open without getting awkward. “Next line?”

He scrolls. A block of text stares back with elbows out: the scene with the landlord rehearsing kindness as surveillance. The verbs wear too many medals; the sentences recruit. He reads one aloud and it trips on its own swagger. “That’s performing,” he says, not accusing the page so much as freeing it of duties. “Flag it.”

“Flagged,” Ellis echoes, and the highlight blooms a soft yellow instead of the punitive red that would have turned the room into court. “Ask: do you want me to propose a cut, or do you want to try first?”

“Try first,” he says, breathing through his teeth in the practical way, not drama. He swaps a metaphor that has appeared in other people’s books for a description of a receipt taped crooked to a door. The replacement sits there like a bruise that knows where it came from. Good. Factual. Not a costume.

A call buzzes the top corner—Gus, because of course—and vanishes when Jaq’s name flashes briefly across the notification with the single word Handled. He smiles into the keyboard and lets the smile be a secret. “Next,” he says, and the chapter moves.

The timer chirps; Ellis mutes it without looking away. “Break?” he offers. The word carries no judgment. It sounds like water placed within reach.

“Keep going,” Asher says, aiming for competence and hitting it by accident. “I’m not sore yet.” He sets the cursor at the beginning of a sentence that used to flinch when he looked at it. It holds eye contact, a small miracle posing as standard practice.

They come to the paragraph where the mother calls to say proud and means proof, the language doing that lopsided thing families invent to avoid bleeding on the rug. Asher clears his throat and reads it out; the air in the apartment tilts toward memory. The tremor makes a brief bid for attention; the brace makes a better case.

“Question,” Ellis says. “Would the scene gain or lose if we cut the last sentence? It explains a thing that your verbs have already shown.” The ask is a hand palm‑up, not a steering wheel.

“It stays,” Asher says, then hears the snap inside the speed and catches it. “No—wait. Tea.” He actually laughs—short, genuine, not a performance—at the absurd relief of saying it.

“Paused,” Ellis says, pen lowered. “What changed?” The quiet carries both of them without turning into a couch.

“It’s my old superstition,” he answers. “If I don’t say it plain, someone will use the gap to tell me what I meant. But the verbs do carry it. The line was insurance I can’t afford in this book.” He toggles the last sentence into the margin and watches the paragraph stand taller, less armored, more his.

“Then let’s leave the margin note as a footstool,” Ellis says, typing Author once kept this clause for self‑protection; cutting with consent. “If later passages bruise from its absence, we’ll revisit.” The promise does not sound like a leash; it sounds like a calendar invite handled by a friend who understands calendars.

Asher leans back an inch, just enough to stop strangling the spacebar. “What about this comma,” he asks, tapping the phrase please, don’t with the tip of the trackpad. “It reads like breath. It also reads like theater.”

“Offer: keep it,” Ellis says. “Ask: is it the character’s breath or the page’s pose?”

“My breath,” Asher admits, then corrects himself. “His breath, but yes, mine. It’s the one place he buys time and means it.” He tries the line aloud both ways. Without the comma, the plea bulldozes. With it, the plea arrives like a palm that refuses to clutch.

“Kept,” Ellis says, and the checkmark returns. “Zooming out,” he adds, eyes flicking to the index on his left. “Where do you want to draw the boundary around how I phrase questions? I tend to use want, function, temperature. I will avoid fix. You can outlaw any word.”

“Outlaw justify,” Asher says immediately, throat tightening on the ghost of arguments he stopped having. “And rescue. You can say test, pressure, or tune. I can handle cut if it’s not a verdict.” The list sounds ridiculous in theory and perfect in practice.

“Done,” Ellis answers, crossing out three words on his pad like an exorcism that requires ink. “Text me if my language slides.” He smiles, the small one that keeps secrets rather than collecting them. “We’re twelve minutes from our second break. One more?”

“Take me to the bus,” Asher says, scrolling to the scene where the driver watches him run and waves him on anyway. The line where he compares mercy to a receipt flutters. He deletes the comparison and replaces it with a detail about the driver’s wrist, a pale band where a watch used to guard time. The paragraph breathes like an open window no one is posing in front of.

The timer chirps again. Ellis angles the pad away. “Break,” he says, and this time Asher nods. Water tastes like water. The room squares its shoulders without anyone being threatened into stamina.

When they come back, the daylight has slid from bright to lacquered, and the doc has the energy of a room where something difficult happened cleanly. Ellis pins a comment above the title with the flat language of a policy that works: Nothing moves without Asher’s yes. The sentence looks like a sign on a door you want to open because it trusts you to behave.

“Final sweep for scope creep?” Ellis asks, pen still, as if stillness itself is part of the terms. “If I overstep, how do you want to say it?”

“Say ‘boundary’ and the page you overstepped on,” Asher says. “Ex: Boundary: bus scene—voice tone. I’ll answer with heard or clarify. No apologies required.” He drags a second sticky to the header: Boundary language standard. The window fan mutters approval like an aunt who hates drama and loves decisions.

Ellis nods. “And if you’re tempted to do violence to a page because it scares you?” His voice loses none of its calm and gains none of that fake concern that smells like performance. “What do you want me to do?”

“Ask if I’m writing for me or the person who wouldn’t listen the first time,” Asher says, quick. “If I say the second, make me put the laptop down for five.” The rule is absurd and perfect. He copies it into the doc like a spell the file system understands.

Fay’s calendar ping returns with a polite cough of glitter; Asher flicks snooze again and adds Publicity after edits: route through Rhea to the bottom of the page. The house returns to kettle noises and distant blenders, ordinary saints doing ordinary work. Your book deserves doors that close.

“Do you want a ceremonial signature?” Ellis asks, half teasing, fully earnest. “I can sign the top comment; you can add an emoji that isn’t coy.”

“Sign,” Asher says. “No emoji. Just names.” He types his, then watches Ellis add his in print steady as a handrail. The two look like the adults they promised to be for the pages under them.

“Test the rules with one more cut?” Ellis offers. “We choose a sentence that hurts to touch and see whether the rules hold.” He waits, eyes down, as if the page itself were listening.

Asher scrolls to a line he has kept for swagger, not truth. It’s clever and clean and false. He reads it aloud and hears the counterfeit in it like a coin on tile. “Kill,” he says, and then, because the body loves ceremony, “with thanks.”

The strikethrough goes on smooth as tape; the paragraph closes ranks, tighter, truer, less loud. Nothing collapses. No one dies. The sentence he saves—two lines down, shy and feral—steps forward and takes its space. The cursor blinks; his pulse agrees with its tempo.

Ellis sets the pen on the pad. “That’s our session,” he says softly. “I’ll send a summary that contains only what we did, not what we meant. You can put it in a drawer, or on the fridge, or set it on fire—it’s yours.” The camera holds both of them without begging either to pose.

“Before we go,” Asher says, throat running a finger along a new edge, “the line about asking.” He highlights it again, the hinge that started the hour. “It stays,” he repeats, not defensive now, just precise. “Not as a wound on display. As a tool that knows its job.”

“Kept,” Ellis replies, marking the margin with a small star. “The door remains a door.” His smile reaches the corner of his eyes and then stops, well‑mannered, not shy. “Leave meeting?”

“Leave meeting,” Asher echoes, but his cursor pauses over the red button. The page under the pinned comment looks like a street after rain: washed, not spotless; navigable, not timid. He clicks. Zoom drops away.

The document waits, sentences arranged like chairs that will remember where the bodies were. He leans forward until his forehead almost meets the bezel, then sits back and lets his tongue trace the place inside his mouth where a worry used to live. The line he decided to keep watches him without asking to be admired. It fits, stubborn and right, the shape of a thing that survived negotiations and stayed because it belongs.