In Nagasaki today, the air was thick with solemnity, speeches, and the unshakable human tendency to swear off dangerous toys while keeping them polished and ready in the basement. The city marked the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing—a moment that forever seared itself into the world’s conscience—by calling for nuclear disarmament. Politicians, dignitaries, survivors, and that one man in the audience who always claps too soon gathered in remembrance, offering a chorus of “never again” that history, unfortunately, has learned to hear as “until next time, maybe, but we’ll totally feel bad about it.”

The ceremonies were heartfelt. Survivors, now well into their nineties, told stories that no human should have to tell—tales of instant devastation, unimaginable loss, and the eerie quiet that followed when an entire city was transformed into ash and shadow. The crowd listened, eyes glassy, nodding at the obvious truth that nuclear weapons are bad. Very bad. Unacceptably bad. So bad, in fact, that every major power with nuclear capability still keeps enough of them around to remake the planet into a fried egg in under thirty minutes.

Because nothing says “we’ve learned from history” quite like an arsenal capable of ending it all, several times over.

The Choreography of Contradiction

Anniversaries like this bring out the best in global rhetoric. Japan’s Prime Minister called for renewed dedication to nuclear disarmament, and world leaders sent statements agreeing in principle while quietly making sure their military budgets stayed as bloated as ever. It’s the geopolitical equivalent of a crash diet: lots of talk about cutting back, followed by a midnight binge in the missile testing range.

Meanwhile, the U.S. ambassador stood with the Japanese delegation in a symbolic moment of unity, nodding solemnly while standing for a nation that still maintains over 5,000 nuclear warheads, give or take the ones we pretend aren’t there. Russia, China, the UK, France—every nuclear club member has the same script: “We must strive for peace, but just in case peace doesn’t work out, here’s a few hundred megatons pointed at your city.”

And it’s not just the big players. Smaller nations have figured out the game: say you want peace, but also casually invest in “research” that’s suspiciously missile-shaped. It’s like showing up to an AA meeting with a flask, insisting it’s “just in case of emergencies.”

Nagasaki’s Ghosts and the Art of Selective Memory

Survivors spoke today not just of the bomb itself, but of the years after—the radiation sickness, the stigma, the slow rebuilding of a city that should never have had to be rebuilt in the first place. They called on the world to ban nuclear weapons entirely, not just reduce them to a “respectable” amount, as if mass annihilation needs a reasonable serving size.

But here’s the thing: humanity’s selective memory is a feature, not a bug. Nagasaki and Hiroshima are often remembered in the same sanitized shorthand—necessary to end the war, tragic but justified, history’s complicated moral math. That’s the narrative, because the alternative is to admit that the world’s most efficient killing device was tested not in a desert, but on two cities full of people.

The survivors remember the details, but history prefers the aerial shot: mushroom cloud, grainy black-and-white, fade to “and then the war ended.” And so, we keep the bombs. We call them deterrents, which is a polite way of saying “you hit me, I hit you harder,” except in this case both people die, and so does everyone watching.

The Disarmament Problem: It’s Not the Math, It’s the Ego

Here’s the part no one says out loud at disarmament ceremonies: getting rid of nuclear weapons isn’t a technical issue—it’s an ego issue. You can dismantle a missile in an afternoon. What you can’t dismantle is the national pride attached to having one. Nuclear weapons are the global equivalent of a luxury handbag: wildly impractical, morally indefensible, but oh, the status.

To admit you don’t need them is to admit you’re not one of the “big players.” And so every year, we attend these anniversaries, hear the same speeches, and then quietly nod to the defense contractors who are already designing the next generation of bombs—smaller, faster, “cleaner,” which is somehow more terrifying than the big, messy ones.

Because what could possibly go wrong with a more efficient nuclear weapon?

The Tourism of Tragedy

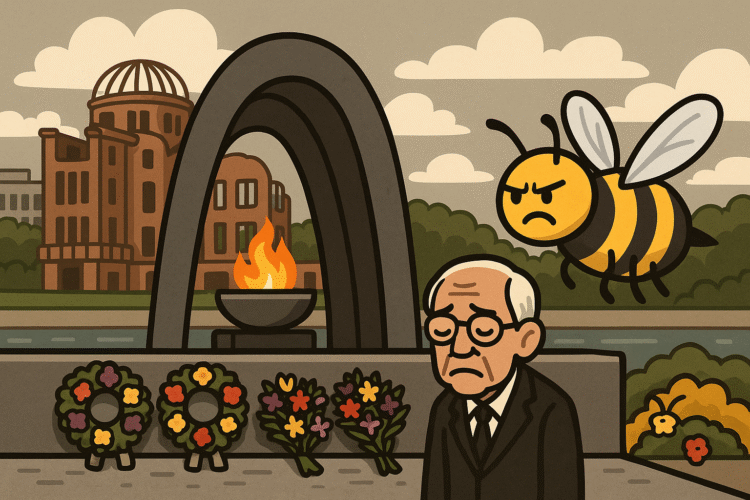

One uncomfortable truth: anniversaries like this bring a certain kind of international tourism. Politicians, media crews, and “peace advocates” arrive to be seen standing in front of the Peace Memorial, preferably in black suits, preferably with a few tears visible for the camera. Then they fly home, where their next vote on military spending will keep the war machine fully funded.

It’s the same pattern every year. The soundbites are predictable: We must learn from history. We must work toward a world without nuclear weapons. We must honor the sacrifices of those who suffered. The words change slightly, but the outcome doesn’t.

The nuclear powers nod along, smile for the cameras, and then head back to the real work: maintaining the stalemate that ensures nobody feels safe enough to disarm, and everybody feels scared enough to keep stockpiling.

The Fantasy of the Big Red Button

What really hangs over these ceremonies, unspoken but heavy, is the fantasy that has kept nuclear weapons alive for 80 years: the idea that they give the person holding the codes an almost godlike power. One push, and you change the course of history. One push, and you’re not just a president or a prime minister—you’re a myth.

It’s the world’s worst security blanket, a comfort in the form of mutually assured destruction. And it’s addictive.

That’s why every time someone calls for “total disarmament,” the other countries glance sideways and think, Sure, you first. It’s a trust fall exercise where everyone knows the other person’s arms are full of knives.

Eighty Years and Counting

Nagasaki’s anniversary is meant to be a warning, a call to conscience. But if the last eight decades have taught us anything, it’s that conscience is easily ignored when power is on the line. The speeches today will be quoted, the images broadcast, and then the world will go back to quietly preparing for the next time we might “need” the unthinkable.

And that’s the quiet tragedy under all the pageantry: the survivors are dying, their stories fading into history, and the weapons they warned us about are still here, sharper and faster than ever.

We mark the years, we bow our heads, we swear it won’t happen again—and then we keep the keys to the vault, just in case.

Final Thought:

The ghosts of Nagasaki have been patient, but they’re not naïve. They know the world still keeps the matchbox next to the gasoline. The speeches are lovely, the memorials moving, but the question lingers in the silence after the applause: When the next button is pressed, will we even have the decency to pretend we’re surprised?