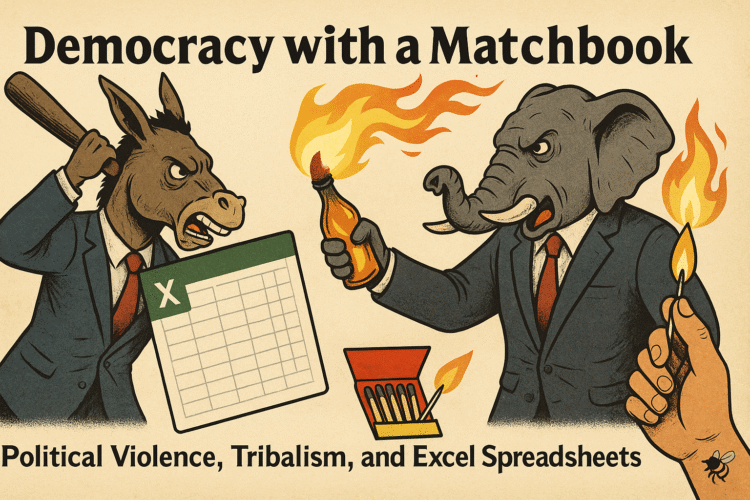

Pod Save America did what it does best: deliver the bad news with a podcast ad break for magnesium powder and underwear that “feels like on-body AC.” The guest of honor was Dr. Liliana Mason, Johns Hopkins political scientist and unwilling Cassandra of our collapsing republic. Her subject? The roots of political violence in America and how, against all odds, we keep tilling the soil for more.

It was the sort of conversation that makes you pause, sip your overpriced seltzer, and mutter, “Surely this isn’t sustainable,” before realizing that “unsustainable” has been America’s national operating system since the Mayflower. Mason laid out the research, the history, the social psychology, and, most damningly, the math. Spoiler: the math says we’re all screwed.

But the beauty of satire—mock-serious, biting, and ironic—is that we can at least enjoy the gallows humor while the gallows is being wheeled into place.

Section I: The Violence Numbers, or How to Make a Pie Chart of Doom

Mason starts with the facts, because unlike most Americans, she believes numbers mean things. Since 2017, she and her co-author Nathan Calmo have tracked Americans’ approval of political violence. The topline: about 15–20% of both Democrats and Republicans say violence is at least sometimes acceptable for achieving political goals.

Translation: one in five of your neighbors is fine with torching City Hall, so long as the torch is wrapped in their party’s colors.

But here’s the kicker: when you ask people, “What if the other side started it?” support for violence skyrockets to 50–60%. That’s not ideology. That’s not principle. That’s tribalism: the emotional Pavlovian response that says, “If they punch, I stab.”

Think about it—most Americans don’t even believe in flossing 60% of the time. Yet the minute you frame violence as payback, we’re suddenly Spartacus with a Glock.

Section II: Henri Tajfel’s Dumb Dots and Our National Religion

Why do we behave this way? Mason points to social identity theory, pioneered by Henri Tajfel, a Jewish chemistry student turned accidental psychologist after surviving a Nazi prison camp by pretending to be French. Tajfel discovered that people would rather “win” than prosper.

In his classic experiment, he asked students to count dots, then randomly labeled them “overestimators” or “underestimators.” When later asked to divide money, participants consistently gave their group less money overall as long as it meant the other group got even less.

This, friends, is America in a nutshell. We would rather sink the boat if it means the other passengers drown first.

The Democrats insist “all boats rise,” armed with bar graphs and CBO projections, while Republicans shout “their boat leaks because of immigrants” and push yours off the dock. The public cheers the sabotage. Excel vs. scapegoats—and guess which one sells better on cable news?

Section III: Democrats’ Excel-Spreadsheet Politics vs. Republicans’ Scapegoat Theater

Democrats, bless their technocratic hearts, still believe politics is a homework assignment. If they can just explain the marginal tax rate clearly enough, America will swoon. “Here,” they say, “look at this detailed plan where all boats rise, wages climb, and healthcare costs fall.”

But the electorate doesn’t want a plan. They want an enemy. They want to watch the other side suffer, preferably on live television with dramatic lighting.

Republicans understand this. That’s why their convention speeches are less policy brief, more WWE promo: “Immigrants are stealing your jobs, your daughters, and your lawn furniture. Vote for me, and we’ll body-slam them back across the border.”

The result? Democrats bring a spreadsheet to a knife fight, and then act surprised when they get stabbed.

Section IV: The 1960s vs. Now—Chaos vs. Organization

Mason draws a chilling contrast. In the 1960s, America was wracked with assassinations, riots, and violent protest. But the violence wasn’t partisan-aligned; both parties had civil rights advocates and segregationists, hawks and doves. The chaos was real, but it wasn’t organized neatly into red vs. blue.

Today, violence is partisan. It has an institutional home. And when violence gets partisan, it risks becoming embedded in governance itself—elections contested with threats, judges intimidated, legislators harassed, and policies enforced not by debate but by force.

This is why the nostalgia-industrial complex—those who sigh, “We survived the ‘60s, we’ll survive this”—is wrong. The ‘60s were bloody, but they weren’t tribal in the same way. Today, our violence is dressed in party uniforms, chanting slogans, and live-streaming for donations. That’s scarier than chaos. Chaos eventually burns out. Partisan violence calcifies.

Section V: Our Existential Timeline—2045, No Majority, No Peace

Mason drops the most haunting fact of all: by 2045, the U.S. will have no racial majority. It should be beautiful—a true melting pot, no group dominant. But history tells us no dominant group has ever yielded power peacefully.

What’s coming isn’t kumbaya. It’s backlash. White Christian men, long accustomed to being default winners, are already acting like toddlers denied a cookie. “They’re replacing us!” they scream, clutching tiki torches from Walmart’s patio aisle.

We’re not watching a fight over tax brackets. We’re watching the psychic breakdown of a group realizing it no longer owns the future. That kind of existential panic doesn’t end with a concession speech.

Section VI: The One-Sentence Solution Nobody Will Utter

Here’s the dark comedy: Mason’s research shows leaders could tamp down violence with a single sentence. Just one. “Don’t commit violence in my name.”

It doesn’t matter who says it—Biden, Trump, your HOA president. When leaders condemn violence clearly, people listen. Approval for violence drops. The nation breathes easier.

But do they say it? Of course not. Trump thrives on gasoline metaphors. Elon Musk dials into far-right rallies to declare, “Violence is coming whether you want it or not.” They don’t sprinkle petrol by accident—they unload tanker trucks.

Imagine the absurdity: survival could hinge on a sentence, but instead, our elites role-play arsonists. It’s like your house is smoldering and the fire chief tweets, “Honestly, a little blaze clears the brush.”

Section VII: Cultural Norms: Compassion or Cruelty on Tap

Mason insists norms matter. Violence isn’t inevitable; it’s taught, modeled, tolerated. Social norms can make compassion contagious or cruelty chic.

And here’s the satire: America, land of the free, has apparently decided cruelty is more fun. Basic decency—condemning assassination, offering condolences, respecting opponents—is treated as weakness. Mockery, dunking, and “owning the libs” (or cons) is our shared lingua franca.

This is not destiny. It’s a choice. But like Tajfel’s underestimators, we keep choosing to lose money as long as it makes the other side poorer. Compassion has no constituency. Cruelty has donors.

Section VIII: Mock Serious Lessons in Tribalism

So what have we learned?

- We don’t want progress; we want payback. Tajfel’s dots weren’t dots; they were destiny.

- We don’t want leaders to calm us; we want leaders to confirm us. Trump screams “fight,” Musk screams “replacement,” and we call it vision.

- We don’t want boats to rise; we want the other boats to sink. Excel sheets cannot compete with scapegoat theater.

- We don’t want democracy; we want our team to win. Even if it means fewer rights, fewer dollars, fewer teeth.

Section IX: America’s Winner-Over-Welfare Psychology

Mock-serious observation: Americans will sacrifice their own material well-being for the emotional high of sticking it to their neighbor. We’d happily lose healthcare if it means the guy across the street loses more. We’d rather our kids go without school lunches if it means “those people” starve first.

This is why Democrats’ “boats rise” fantasy is doomed. No one wants all boats to rise. They want the yacht club sunk, the jet ski confiscated, and the pontoon blown sky-high.

And here’s the irony: everyone thinks they’re the underdog. Rural voters think elites oppress them. Urban voters think rural reactionaries oppress them. Billionaires think taxation is persecution. Poor people think billionaires are stealing their crumbs. Everyone is Spartacus, but no one is free.

Section X: The Sprinkled Petrol Nation

Mason ended with the metaphor that should haunt us: political violence is not yet an epidemic. But we are sprinkling petrol everywhere. Rhetoric, polarization, tribal sorting—they’re accelerants waiting for the match.

And what is America best at? Matches. We love a spark: a viral video, a trending outrage, a 24-hour news cycle. The conditions are dry, the fuel abundant, the arsonists eager. All we lack is ignition.

The Final, Haunting Observation

America is not drowning in violence yet. We are not Yugoslavia, not Rwanda, not the 1960s redux. But we are a nation of Tajfel’s underestimators, gleefully giving ourselves four dollars to make sure the other side only gets three. We’re laughing as we tip gasoline cans across the lawn, sneering that the other tribe’s house will burn hotter.

Dr. Mason’s warning isn’t prophecy; it’s diagnosis. Violence here is not random. It’s partisan. It’s tribal. It’s organized. It’s waiting.

And while Democrats count boats and Republicans torch docks, we—the people—play with matches.

We are not yet in an epidemic of violence.

We are sprinkling petrol everywhere, waiting for the match.