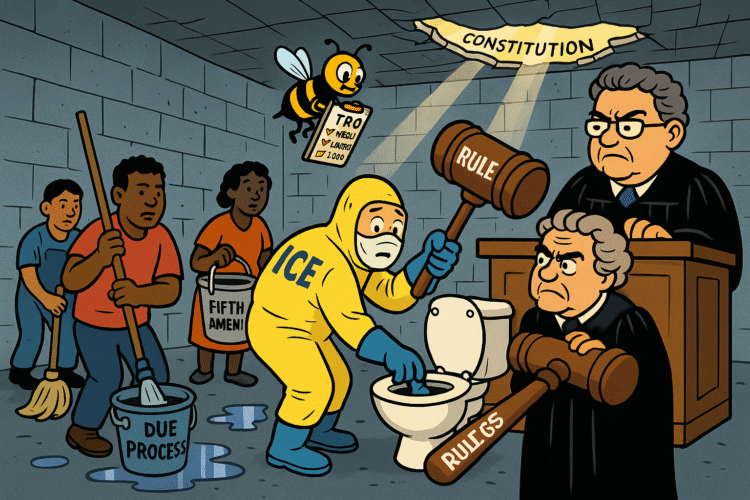

Somewhere between bureaucracy and mildew, the Constitution just won a small victory. This week, a federal judge in Chicago decided that the Bill of Rights applies even when the floors are wet. U.S. District Judge Robert Gettleman issued a temporary restraining order forcing Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to clean up the Broadview detention facility in Illinois, a place so notoriously squalid that its nickname among advocates is “The Black Box.” The order reads less like a legal document and more like a desperate plea to restore basic humanity to a warehouse of invisible people.

For the first time in years, the federal judiciary has said out loud what ICE has whispered through budget requests and deleted videos: if you detain human beings, you have to treat them as such.

Act I: The Smell of Accountability

The Broadview facility, run by ICE’s Chicago field office, was the subject of recent ACLU filings describing conditions that would make a landfill blush. Detainees testified about sleeping on floors next to overflowing toilets, eating food they couldn’t identify, and being denied soap, privacy, or access to lawyers. Some slept on yoga mats next to drainage grates. Others begged for phone access to contact attorneys but were told the system was “down.” Video evidence of these conditions allegedly went missing, as though hygiene violations could be redacted like classified documents.

Judge Gettleman’s order cuts through the bureaucratic stench. Effective immediately, ICE must ensure working toilets, provide edible meals, supply hygiene products, establish confidential phone lines for attorneys, and maintain a detainee tracking log that actually reflects who’s inside the building. The log, by the way, is a direct response to testimony that families and lawyers often had no idea where their clients had been taken—a problem ICE described with the technical term “transfers.”

To summarize: the U.S. government needed a federal court to remind it that people should not sleep next to toilets, and that their lawyers should be able to find them without GPS triangulation.

Act II: Rule 65, Now with Lysol

Legally, this is what’s called a temporary restraining order under Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. That means the judge determined there was an immediate and irreparable harm at stake, that the plaintiffs (in this case, a coalition led by the ACLU) are likely to succeed on the merits, and that the balance of equities and public interest favor intervention. Translation: it’s so bad we can’t wait for trial to clean the bathrooms.

Judge Gettleman’s ruling is tailored but enforceable. It doesn’t attempt to rewrite immigration law or abolish detention altogether. It simply forces the government to meet minimum constitutional standards under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, which protects against conditions so poor they amount to punishment without conviction. Access to counsel is also constitutionally grounded: if you can’t reach your lawyer, your rights exist only in theory, not practice.

The Fifth Amendment, it seems, has a sense of smell.

Act III: Bureaucracy Meets Bleach

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) now face a logistical puzzle: how to comply quickly without admitting fault. ICE has already claimed that Broadview is merely a “short-term holding facility,” as if that excuses sanitation failures. The government’s position, summarized politely, is that rapid clean-up could “hinder enforcement operations.” In less polite English: we’d love to fix it, but then we’d have to stop doing it this way.

The TRO requires compliance by Friday. That means ICE must provide a status update confirming that toilets flush, food meets nutritional standards, hygiene kits exist, and confidential attorney calls are functioning. If not, contempt proceedings follow—a polite phrase for judicial fury. In the meantime, staff must compile phone records and logs documenting who entered and exited the facility in recent weeks. Think of it as the civil-rights version of retrieving cockpit voice recorders after a crash.

The court also ordered that any destroyed or deleted footage be addressed in a future hearing, a subtle warning that “lost evidence” may soon become “obstruction.”

Act IV: The Timeline of Filth

The road to this order began last week with a 63-page filing by the ACLU of Illinois and partner organizations, combining testimony from detainees, volunteers, and attorneys. The document described overcrowded rooms without ventilation, temperatures swinging from freezing to suffocating, and guards who refused to identify themselves by name or number. It also detailed repeated denials of attorney access, with ICE insisting the facility was “too busy” for phone calls.

Investigative journalists had already flagged similar issues, including a whistleblower’s claim that ICE staff deliberately delayed repairs to keep costs low. The story gained traction when members of Congress requested a site visit, which ICE initially denied, citing “security protocols.” In Washington-speak, that’s shorthand for “we don’t want you to see the plumbing.”

By Tuesday afternoon, Judge Gettleman had read enough. The TRO dropped like disinfectant on a public relations wound.

Act V: The Legal Mechanics of Cleaning Up

For those unfamiliar with how federal orders intersect with government machinery, compliance now travels a gauntlet. The DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties will likely issue directives to the Chicago field office, which then contracts with local vendors for repairs and supplies. OMB must approve any emergency spending above threshold levels, meaning even soap purchases get logged in spreadsheets.

If ICE argues that procurement delays make immediate compliance impossible, the court can issue a contempt finding or extend the TRO into a preliminary injunction. Translation: if they ignore the deadline, they’ll be mopping the floors with subpoenas.

Meanwhile, DHS lawyers must draft affidavits proving compliance, complete with time-stamped photos and maintenance receipts. Each affidavit will read like a grim parody of government efficiency: “Toilet #6: Operational as of 3:22 p.m.”

Act VI: The Fifth Amendment Learns Patience

The Fifth Amendment’s due process protections extend beyond trial rights—they cover the conditions under which the government detains people. Courts have long held that civil detainees, unlike criminal inmates, cannot be subjected to punitive treatment. The fact that ICE routinely flouts this principle is an open secret.

Judge Gettleman’s order, while narrow, reaffirms a basic truth: cleanliness and counsel are not luxuries. They are constitutional.

Access to attorneys is especially crucial. The court’s insistence on confidential phone lines addresses years of complaints that ICE monitored calls or limited access to certain lawyers. Without privacy, due process becomes performance art.

The TRO’s structure—immediate, enforceable, and time-limited—reflects judicial fatigue. Judges in Chicago have been circling this issue for years, issuing warnings and soft rebukes that ICE treated like weather forecasts: inconvenient but ignorable. This time, the order comes with an expiration date that forces a hearing, ensuring the agency can’t hide behind paperwork.

Act VII: The Government’s Defense—“We’re Busy”

ICE’s official response was a masterclass in missing the point. “Broadview is a short-term facility designed for processing, not long-term housing,” the agency said. In other words: people don’t stay long enough to notice the filth.

But detention, short or long, triggers the same constitutional floor. A day without sanitation or access to counsel is still a day of unlawful deprivation. The government’s other argument—that rapid fixes could disrupt operations—is equally damning. If cleaning the bathrooms hinders enforcement, maybe enforcement is the problem.

One official, speaking anonymously, even claimed the TRO “could set a dangerous precedent.” Yes, the precedent of treating human beings like human beings. The horror.

Act VIII: The Black Box Cracks Open

Broadview’s nickname, “the Black Box,” comes from its secrecy. Attorneys have long complained that detainees disappear there without notice, with families unable to confirm location or status. The new order’s requirement for a real-time tracking log aims to break that opacity. The log will function like an accountability flight recorder: who entered, when, for how long, and where they went next.

It’s a small but radical shift toward transparency in a system built on invisibility.

The deleted video remains an open wound. ICE claims footage was “automatically overwritten” due to storage limits. The court, unconvinced, has requested documentation of data retention policies. Expect hearings to explore whether “automatic” is just another word for “convenient.”

Act IX: The Human Cost Behind the Legalese

Behind every footnote in the court’s order is a person who slept on a floor, missed a hearing, or lost hope. The TRO’s clean prose belies the chaos it addresses. “Adequate meals” means no more expired sandwiches. “Working toilets” means no more plastic buckets. “Access to counsel” means a phone line that doesn’t drop after thirty seconds.

For advocates, it’s vindication. For detainees, it’s survival. For ICE, it’s paperwork.

Act X: The Coming Checkpoints

Friday’s compliance deadline is only the beginning. In the next few days:

- Sanitation Inspection: Independent monitors will document the cleanup. If conditions remain unsafe, the court can impose fines or contempt sanctions.

- Attorney Access Audit: The ACLU will test the phone system to verify confidentiality. Any interference triggers immediate motion practice.

- Food Quality Review: Contractors must submit invoices proving meal upgrades. “Adequate nutrition” is no longer a euphemism for vending machine leftovers.

- Tracking Log Transparency: ICE must provide a functioning log by week’s end. If names still vanish, the judge may appoint a special master.

- Congressional Visits: Lawmakers are already seeking entry. ICE can’t claim “security risk” forever. Cameras will follow.

- Contempt Threats: If ICE drags its feet, expect a contempt hearing with witnesses, fines, and public embarrassment.

The next hearing will decide whether to extend the order into a permanent injunction or pivot to a consent decree—essentially a court-supervised reform agreement.

Act XI: Parallel Battles

Outside the courtroom, the press and Congress are waging their own access fights. The ACLU’s legal team has petitioned for open inspection rights, while journalists are seeking entry under Freedom of Information Act requests. ICE’s refusal to allow independent tours has drawn comparisons to the Trump-era “tender age” facilities, where secrecy masked systemic neglect.

Congressional oversight committees are already drafting letters demanding answers from DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. The political calculus is simple: no one wants to defend dirty toilets on camera.

Act XII: The Chicago Doctrine

Judge Gettleman is not alone. Chicago’s federal bench has become an unlikely epicenter of accountability, repeatedly rejecting ICE’s attempts to operate beyond constitutional limits. From prolonged detention rulings to access-to-counsel orders, the message is consistent: the law applies north of the border too.

In a city famous for corruption trials, it’s oddly poetic that justice now smells faintly of bleach.

Coda for a Republic That Forgot How to Mop

The Broadview order will not fix the system. It will not make immigration humane or bureaucrats moral. But it reaffirms a principle that should not need reaffirming: decency is not optional.

For decades, ICE has operated in the shadows, blending enforcement with neglect and calling it efficiency. It built facilities without accountability, staffed them without oversight, and treated detainees as administrative noise. Now, for once, the noise reached the courtroom.

If the agency meets the Friday deadline, it will be the cleanest thing ICE has done in years. If it doesn’t, the contempt hearing will be the hottest ticket in town. Either way, the Constitution finally gets to stretch its legs—and maybe, just maybe, wash its hands.