We like to tell ourselves that human beings are noble, empathetic creatures. We write novels about kindness, sing songs about love, build religions around compassion. But spend thirty seconds in line at Starbucks or thirty minutes Doordashing lukewarm Chipotle to someone in yoga pants, and the truth hits you in the face like a soggy burrito bowl: shit rolls downhill, and people love standing uphill with their arms crossed.

Hierarchy isn’t an accident of history; it’s the base code of human software. No matter where you are in life—CEO or dishwasher, barista or senator—you are always calculating where you stand on the invisible ladder and who you can look down on. The whole of civilization is basically one long game of “at least I’m not that guy.”

And nothing reveals this more clearly than the world of hospitality and gig work. If you ever want to see human nature stripped of pretense, try delivering fast food to a three-star hotel at 11 p.m. You’ll find managers who are themselves ground down by corporate overlords—but who light up with glee at the opportunity to remind you that you, the Doordasher, exist somewhere below the mop bucket.

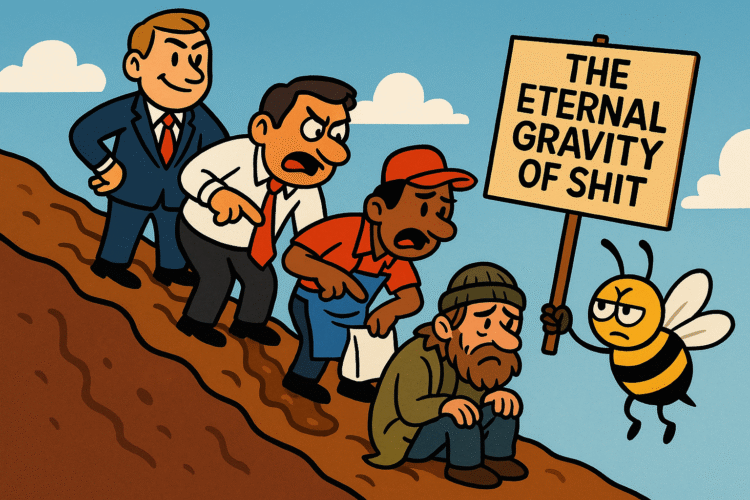

Gravity Always Wins

“Shit rolls downhill” isn’t just a vulgar proverb—it’s Newtonian law with a customer-service badge. The stress, cruelty, and insecurity at the top don’t evaporate; they simply trickle downward, gathering speed and stench along the way. The CEO berates the regional manager, who snaps at the hotel general manager, who dumps it on the front desk clerk, who smirks at the line cook, who takes it out on the Doordasher holding two bags of Taco Bell and no dignity.

The miracle is that we’ve all agreed to this without saying a word. We build whole systems on it: workplace hierarchies, schoolyard cliques, caste systems, political parties. They all run on the same principle—that there must always be someone beneath you, and it is your sacred right to remind them of it.

Marginalization Loves a Ladder

You’d think that people who know what it’s like to be kicked down would resist the urge to kick others. You’d think that disenfranchised groups would extend empathy sideways and downward, forming solidarity in the shared experience of being treated like garbage.

And yet, history (and your local restaurant) show the opposite. Marginalized communities build their own hierarchies like clockwork.

- Within the working class, there are “respectable” workers and “dirty” workers.

- Within immigrant communities, there are first-generation snobs sneering at the next arrivals.

- Within queer spaces, there are hierarchies of desirability, privilege, and purity tests.

- Within every “inclusive” movement, there’s always someone quietly being excluded.

Because empathy is exhausting, but hierarchy is easy. The second you feel small, you look for someone smaller. It’s not justice—it’s math.

Hierarchies Within Minorities

I’ve seen this up close, too. Many African nurses I’ve worked with—immigrants who built careers despite staggering challenges—still looked down on African Americans, repeating the same stereotypes about laziness or crime that white conservatives mutter on talk radio. It wasn’t because they didn’t know struggle; it was because hierarchy demanded that they find someone “less than” to mark their own progress.

The same exists in Latinx communities. Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, Central Americans—there are whole internal ladders of who is seen as “better,” “harder working,” “more respectable.” I’ve lived the half-Puerto Rican identity, and I can tell you there are definite groups people assume are beneath them: natural-born Puerto Ricans vs. migrants, island-born vs. mainland-born, citizens vs. undocumented. Even within a group that’s treated as second-class in the broader country, there’s always a game of “at least I’m not them.”

That’s the perversity of hierarchy—it doesn’t vanish in marginalized communities. It multiplies. Instead of empathy, there’s sorting. Instead of solidarity, there’s suspicion. Everyone wants to make sure someone is beneath them, even when they’re already at the bottom of someone else’s ladder.

The Doordash Diaries

Delivering food in America is like serving as an unofficial anthropologist. You get to see how people treat you when you are, to them, invisible. The hotel clerk who won’t even look up when you drop off their dinner. The server who waves you away from the side door like you’re a raccoon rooting through the trash. The customer who leaves a $0.50 tip on a $40 order and calls it “generous.”

These aren’t cartoon villains—they’re normal people who’ve simply learned the pleasure of pushing shit just a little further downhill. They may spend their entire shift being screamed at by customers, but when you arrive with their Uber Eats bag, suddenly they get to be the customer. And the transformation is glorious. For a brief moment, they are queen of the hill, and you are beneath them.

It doesn’t matter that their “hill” is a sticky linoleum floor behind a service desk. Hierarchy is relative. It only requires one thing: someone lower than you.

Caste by a Thousand Cuts

We like to point at India’s caste system or medieval Europe’s serfdom as if hierarchy is something exotic, something other cultures invented. But America has its own caste system, just less honest about it. We dress it up in capitalism and call it “customer service.”

The logic is the same: someone is always disposable, always invisible, always less than. And everyone, no matter how low, clings to the hope that they’re at least above someone else. That hope is what keeps the system alive.

The janitor laughs at the delivery guy. The delivery guy rolls his eyes at the unhoused person outside. The unhoused person sneers at the addict in the alley. The addict spits at the sex worker. The sex worker shakes their head at the dealer. It never ends. Shit always finds new slopes.

The Illusion of Empathy

We love to romanticize empathy, but it’s rationed like gas in wartime. We give it upward sparingly—to celebrities, to tragic stories that pass through our timelines. We give it sideways to friends if we’re not too tired. But downward? Downward empathy is rare.

Because empathy requires seeing yourself in someone else, and the last thing people want to see is themselves at the bottom. It’s safer to believe you’re nothing like “those people.” That’s why the same working-class folks who suffer wage theft will still rant about welfare queens. That’s why queer communities can fracture over who “counts” as queer enough. That’s why immigrants repeat the rhetoric used against them on newer arrivals.

We ration empathy because the hierarchy demands it. If we empathized too much, the whole system would collapse.

Hospitality as Theater

Hospitality, ironically, is where this dynamic shines brightest. The entire industry runs on pretending to be nice to customers while stabbing each other with invisible knives behind the scenes.

- Servers hate bartenders.

- Bartenders hate cooks.

- Cooks hate managers.

- Managers hate corporate.

- Corporate hates everyone.

And when a Doordasher shows up? Jackpot. The hierarchy needs its bottom rung, and there you are, sweaty and clutching a McDonald’s bag, a living receptacle for everyone else’s resentment.

The tragedy is that the hospitality industry is full of people who know exploitation firsthand. They work double shifts, earn poverty wages, get screamed at for sport. And yet, instead of solidarity, the system rewards them for passing the pain downward. They may not have power over their boss, but they can roll their eyes at you for asking where the pickup counter is.

The Politics of Downhill

This isn’t just workplace psychology—it’s national politics. Our entire political ecosystem is a master class in rolling shit downhill.

The billionaire class siphons wealth, then convinces middle-class voters their real enemy is immigrants. Politicians strip social services, then convince struggling workers that the unhoused are the problem. Police unions deflect scrutiny by turning communities against each other.

It’s brilliant in its cruelty: keep everyone so busy sneering downward that no one ever looks up.

And it works, because humans crave hierarchy. People would rather be second-to-last than equal. Better to be “not like them” than to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the people beneath you.

Why We Need Someone Beneath Us

The truth is that hierarchy comforts us. Knowing there’s someone beneath you creates the illusion of safety. “At least I’m not that poor.” “At least I’m not that fat.” “At least I’m not that desperate.” The comparisons are endless, the relief addictive.

It doesn’t matter if you’re broke, broken, or one paycheck from ruin—if you can point to someone else and say “I’m above them,” the system has you right where it wants you. You feel powerful while remaining powerless.

This is why marginalized communities fracture. This is why solidarity is so rare. Because unity requires leveling the ladder, and most people would rather cling to one rung above the bottom than risk standing on equal ground.

The Cruel Joke of Progress

We pretend progress is about eliminating hierarchies, but often we just rearrange them. Civil rights laws get passed, women enter the workforce, queer people win marriage rights—but the hierarchy adapts. Racism, sexism, homophobia—they mutate, they redirect. You may rise, but someone else gets shoved lower.

Even progressive spaces are guilty. Activism loves its own hierarchies of purity and righteousness. If you’ve ever watched progressives eat each other alive online, you’ve seen the same shit rolling, just in rainbow wrapping paper.

What I’ve Learned From the Road

Doordashing taught me this lesson more clearly than any textbook. Watching people treat you as “less than” for no reason other than your position in the transaction exposes the entire structure.

It’s not personal. It’s gravitational. People who are powerless in one space will flex in another. It’s the same reason bosses scream at employees after being humiliated by their bosses. The same reason parents hit their kids after being crushed by the world. The same reason bullied children become bullies.

Shit rolls downhill. Always.

Can We Stop the Avalanche?

The cynical answer: no. Hierarchy is too ingrained, too rewarding. As long as people feel insecure, they’ll look for someone to stand above.

But the slightly hopeful answer is that individuals can choose to interrupt the flow. You can hand the Doordasher a smile and a real tip. You can refuse to mock the unhoused man outside the restaurant. You can look sideways instead of down.

It won’t dismantle the system, but it will slow the shit. And slowing it—even a little—matters.

Summary of Hierarchies and Shit

Humans are addicted to hierarchy. From hospitality to politics, marginalized groups to billionaires, everyone seeks someone beneath them to feel secure. Shit rolls downhill because it must: the system depends on it. The Doordasher is beneath the server, the server beneath the manager, the manager beneath corporate, and corporate beneath billionaires—who answer to no one. Even within minorities, hierarchies flourish: African immigrants vs. African Americans, different Latinx groups measuring each other, Puerto Ricans divided by birthplace and citizenship. We could choose solidarity, but more often we choose comparison, because hierarchy is easier than empathy. Until we stop measuring our worth by who we can look down on, the hill will always slope, and the shit will always roll.