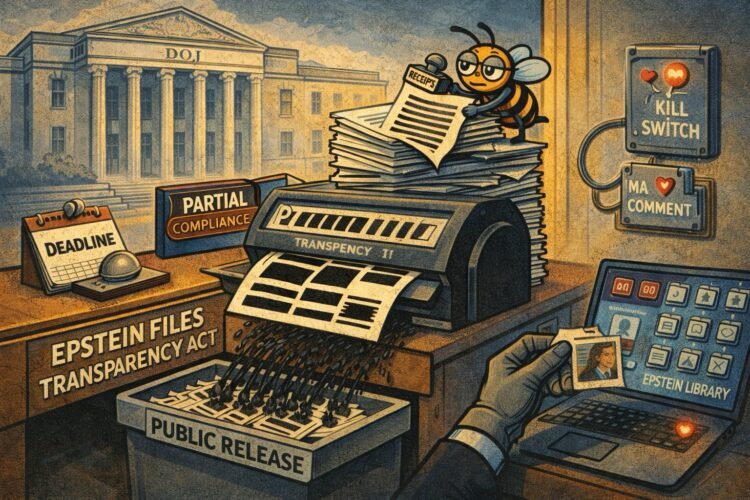

A statutory deadline, a disappearing website, and the federal government’s newest genre: partial compliance theatre.

Congress did that rare Washington thing where everyone pretends the job still matters. They passed a law. They put a deadline in it. They specified what had to be released. They even limited the excuses, the usual ones about victim protection, sensitive personal information, and legitimately protected law enforcement details. It was supposed to be one of those simple civic moments where the system performs basic competence, like a smoke detector chirping exactly when it should.

Instead, the Justice Department answered with a document dump that looked like it was assembled by a tired intern, a terrified lawyer, and a high-powered blackout marker that hasn’t felt joy since the first time it met paper.

Here’s the clean, boring part, the part that is not supposed to be controversial because it’s literally the point of the statute.

The Epstein Files Transparency Act required the Department of Justice to publicly release a defined set of Epstein-related investigative and case materials by a fixed deadline set by Congress. The law contemplated redactions, but the redactions were supposed to be narrow and purposeful. Hide victim identities. Protect sensitive personal information that doesn’t belong on the internet. Shield genuinely protected law enforcement details, the kind that would jeopardize an active investigation, expose sources, or compromise methods. In other words, redact like an adult, not like a cartoon villain trying to erase the concept of oversight.

That was the assignment.

Then the deadline arrived, and DOJ leadership under Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche delivered something that lawmakers from both parties are now describing as a dodge, not a fulfillment. Not “we need a little more time to do this safely,” but “here is a pile of paper that looks like compliance from far away and like concealment up close.”

The rollout began the way modern institutional embarrassment often begins, with confident messaging and a public website designed to signal seriousness. DOJ launched a public-facing “Epstein Library” and began posting thousands of files. The volume was impressive in the way a warehouse is impressive. You can stand in front of it and admire the scale without learning what’s inside.

And then people opened the boxes.

CBS reviewed the initial release and found at least 550 pages that were fully blacked out, not partially redacted, not carefully edited, just obliterated. Entire pages turned into rectangles of darkness, as if the Justice Department was filing a report from inside a solar eclipse. The effect wasn’t privacy protection. It was a refusal to communicate.

NPR’s reporting and analysis added another detail that landed like a siren in a quiet room: some of the most sought-after material was not merely redacted, it was erased at scale. One example that kept coming up was 119 pages of New York grand jury testimony that appeared in the trove as pure blackout. Lawmakers who wrote the law described the drop as incomplete and demanded explanations for what was missing and why.

This is the moment where DOJ’s defense became a familiar refrain. Blanche described the release as “partial compliance,” framed as necessary to protect survivors, and suggested more would come later. The department positioned itself as the adult in the room, holding back details because the public cannot be trusted to handle the truth responsibly.

That’s a charming argument, right up until you remember the law did not ask DOJ to decide whether the public deserves the information. The law asked DOJ to release the information, with narrow redactions to protect victims and legitimate investigative needs. Congress wrote that balancing act into the statute. DOJ’s job was to execute it, not replace it with a new policy of “trust us, later.”

This is why critics are calling it noncompliance instead of prudence. A careful redaction looks like surgery. A blanket blackout looks like a tarp thrown over a crime scene because someone important might walk by.

The optics got worse when the website itself started behaving like it had stage fright.

Within a day, at least 16 files posted to the DOJ site disappeared. No public notice. No clear explanation at the time. Just a set of links that worked one day and then didn’t, which is a fun experience if you’re streaming a sitcom and a less fun experience if you’re trying to review materials Congress ordered the government to release.

Among the missing items was a Trump-related photo that became the centerpiece of the entire fiasco, not because it proved anything on its own, but because it demonstrated the system’s reflexes. The image showed a desk drawer with several photographs, including one featuring Trump, and it vanished from the site without warning. Then, after a burst of public scrutiny, it was restored. DOJ explained the removal as a victim-protection review flagged by prosecutors, and Blanche said the concern was about the women in the photo, not Trump himself.

Maybe that’s true. Maybe it’s even responsible in isolation. But the problem is what the sequence communicates: the department posted material, removed it without public notice, and then restored it after the public noticed. That’s not transparency. That’s getting caught rearranging the shelves and calling it housekeeping.

In a normal transparency process, you do the review first. You redact what the law permits. You post a stable record. You maintain it. You do not publish, delete, and restore like a social media manager trying to fix a typo after the screenshot has already gone viral.

At this point, the story stopped being about Epstein materials in the abstract and became about how a federal agency behaves when it’s ordered to show its work.

Because “partial compliance” is not actually a legal category Congress intended to invent. It’s a phrase that sounds reasonable until you translate it into plain English. It means: we decided our interpretation of the law matters more than your deadline.

So lawmakers did another rare Washington thing. They got mad in stereo.

The co-authors and bipartisan supporters of the law began threatening enforcement tools that Congress mostly keeps in a glass case labeled “Break In Case of Executive Branch Nonsense.” Contempt of Congress started circulating as a real possibility. So did subpoenas and court actions to compel production. There was talk of inherent contempt, the old-school congressional power that can include direct coercive measures like daily fines, a concept that sounds archaic until you realize it was designed specifically for moments when the executive branch decides it can ignore the legislature.

And then the circular problem arrives, right on schedule, like a bureaucratic punchline.

Criminal contempt referrals typically run through the same Justice Department that is being accused of stonewalling. Congress can vote to hold an official in contempt, refer it for prosecution, and then watch DOJ politely place the referral in a drawer labeled “No Thanks.” It’s the institutional equivalent of calling customer service and discovering you have reached the company’s voicemail.

That circularity is why the current fight is so fraught. If DOJ is willing to treat a statutory deadline as optional, then the normal enforcement pathways become comedy. The courts become the next arena, with lawsuits that could attempt to force compliance with the statute’s plain requirements. Inspectors general and internal audits become potential pressure points, because they can create paper trails about who ordered what redactions, who decided to pull files, and who signed off on an approach that looks less like protection and more like disappearance.

And because Washington has no sense of irony left, impeachment talk has entered the chat, the political equivalent of a fire alarm that everyone hears but nobody wants to pull because the building might collapse if they do.

In the middle of all this is the law itself, still stubbornly plain.

Congress said: release the defined set of unclassified Epstein-related investigative and case materials by the deadline, with narrow redactions for victim identities, sensitive personal information, and legitimately protected law enforcement details. DOJ responded with massive blackouts, missing categories, and a website that briefly lost files like it was trying to remember where it put them.

If you want to understand why critics are calling this concealment rather than survivor protection, focus on the difference between editing and erasing.

Editing is when you remove a victim’s name, blur a face, redact a personal detail that could lead to identification. Erasing is when you black out entire pages, with no meaningful explanation of what category of protection justified the blackout. Editing is when you post a stable, searchable record that the public can rely on. Erasing is when documents disappear overnight without notice, as if transparency is a pop-up shop.

DOJ argues that survivor protection requires caution, and that’s not a trivial concern. Epstein’s crimes involved exploitation, coercion, and extensive harm. The state has obligations to protect survivors from further exposure and to avoid turning trauma into a public spectacle. But that’s the point of narrow redactions. The statute already anticipated that protection. It did not authorize blanket darkness.

A system can protect victims and still comply with the law. The current approach looks like it’s protecting the institution first.

Which brings us to the political reality humming beneath the legal dispute. The Epstein story is a magnet for conspiracy theories, opportunistic outrage, and performative transparency. It’s also a story with real victims who have been repeatedly used as props by people who want to win arguments, build careers, or weaponize information. In that environment, a competent federal response would have been boring. It would have been methodical. It would have been stable.

Instead, DOJ produced the kind of chaotic release that makes everyone angrier and no one more informed.

The near-term decision points are not abstract, they’re mechanical.

Will courts force a clearer standard of compliance, limiting DOJ’s ability to substitute “partial compliance” for the actual statutory mandate. Will Congress escalate beyond statements and hearings into direct coercive tools, including inherent contempt fines that create immediate personal stakes for officials who are currently insulated by institutional circularity. Will inspectors general or internal reviews produce a clear record of who ordered the redactions and the removals, what legal rationales were used, and whether political considerations played any role in how the public record was shaped.

And maybe the most important question, the one that will echo beyond this particular mess, will Congress tolerate the precedent being set here.

Because if Congress can pass a release law with a hard deadline and narrow redaction authority, and DOJ can respond with a blackout marker and a shrug, then every future transparency statute becomes optional theater. Lawmakers can write the script, but the executive branch gets final cut.

That is not oversight. That is a staged reading.

Fine Print for People Who Thought “Statutory Deadline” Meant Anything

The cynical genius of a blackout dump is that it lets everyone claim victory while the public gets nothing usable. DOJ gets to say it released thousands of files. Politicians get to say they demanded transparency. Cable panels get to debate motives. And the only thing that quietly changes is the precedent: that Congress can order sunlight and the executive branch can deliver a box of eclipses. If the government can comply by erasing, then transparency stops being a policy and becomes a costume.