When the government stops working, it also stops counting who is hurting, and calls that “temporary.”

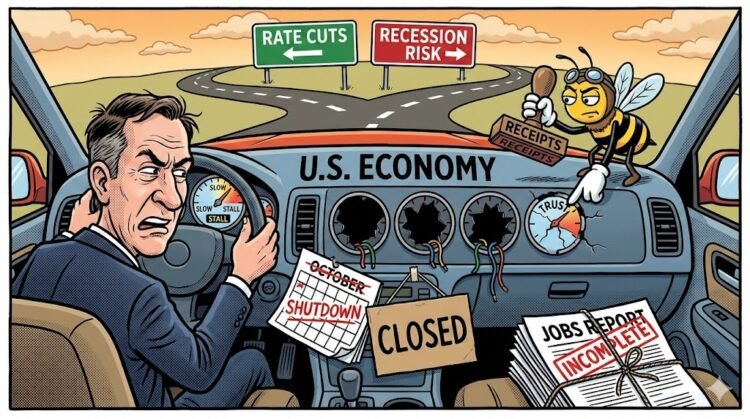

The federal shutdown this year did not just lock doors, pause permits, and turn “please hold” into a lifestyle. It reached into the country’s basic economic dashboard and started pulling out wires like a bored teenager under the hood of a car they do not have to drive. We learned this week, not through a dramatic announcement, but through the quiet panic of economists reading delayed jobs numbers the way sailors read clouds. The data finally arrived, late and tired, expected to show roughly 50,000 jobs added last month and unemployment rising to around 4.5 percent, the highest in several years. The report also arrived with a warning label, because the shutdown disrupted data collection so badly that parts of the story are incomplete, distorted, or simply missing.

Normally, a monthly jobs report gives the country something close to a shared reality. It is not perfect, but it is a ritual that tells the Fed, investors, employers, and households whether the labor market is cooling gently or cracking. This time, the ritual showed up with half the instruments missing and a note that says, “We did our best.” That note is not reassuring when the question is whether people are losing work, dropping out, or being pushed into the shadows of the labor force where nobody counts them until the next crisis.

The shutdown’s most important casualty was not a number, it was confidence in the act of measurement itself. There was an unusually incomplete picture because the Bureau of Labor Statistics could not fully run the household survey that normally produces the unemployment rate and crucial details about who is working and who is not. That survey is where the labor market becomes human and specific. It tells us about participation, demographics, and the texture of joblessness across groups. When it fails at a historic level, the unemployment rate starts to look like a headline without a story behind it.

The country is now in the awkward position of receiving a jobs report while also being told the jobs report may not be able to see the country clearly. That turns a routine release into a credibility test. It is one thing to debate whether the labor market is slowing. It is another thing to realize the government might not be able to count the country’s pain accurately enough to respond to it, and still expects everyone to make trillion-dollar decisions on schedule.

The Payroll Numbers Are Fine, It’s the People Who Are Missing

Part of the reason this gets so confusing is that the jobs report is really two different machines taped together and presented as one story. Nonfarm payrolls come from a survey of employers, and that employer side can be pieced together more easily even when government operations are disrupted. Businesses submit payroll information, agencies compile it, and the headlines arrive with the familiar confidence of a scoreboard. The payroll figure can still look crisp, because it is built from paperwork that exists in corporate systems, not from knocking on the door of the public and asking, “Are you working.”

The broader labor-market story comes from the household survey, and that one is where the shutdown did real damage. Household data explains whether unemployment is rising because people are losing jobs, or because more people are actively looking again. It explains whether participation is falling because workers are discouraged, or because they are retiring, caregiving, or simply unable to find something that pays enough to justify the commute. It explains who is being hit first, and where cracks are forming. Without it, the country can still count jobs, but it has a harder time understanding workers.

This is how you end up with a report that may show modest job growth and a higher unemployment rate, and still cannot tell you which version of reality you are living in. Is the labor market cooling the way policymakers have hoped, with gradual slowing and less inflation pressure. Or is it cooling the way families dread, with layoffs, shrinking hours, and people quietly giving up. The difference matters, and the shutdown made it harder to know which one is happening.

If you are wondering why anyone should care about the finer points of surveys, consider who is forced to make decisions with this information. The Fed has to decide whether to cut rates, hold steady, or stay higher for longer. Investors have to price not just rate cuts, but recession risk, and those are two different stories with two very different sets of winners and losers. Employers have to decide whether to keep hiring, freeze hiring, or start quietly sharpening the knife. Households have to decide whether they can take on a car payment, move, or replace a broken appliance without gambling the mortgage.

Everyone is being asked to navigate with missing gauges.

The Economy Is Jittery, and We Just Took Away Its Eyes

Even in a calm year, jobs data is a negotiation between certainty and noise. Revisions happen. Seasonal adjustments happen. The numbers get argued over by people with spreadsheets and feelings. But in a shutdown year, the noise is not a normal statistical blur. It is structural, caused by the government failing to perform one of its most basic functions: collecting information about its own people.

That failure turns into policy risk immediately. If the jobs report looks weak, markets may lean toward rate cuts. If the weakness is real, cuts could help cushion a slowdown. If the weakness is a statistical artifact of disrupted surveys, cuts could arrive too early, and the Fed could be seen as responding to ghosts. Meanwhile, if the report looks stronger than reality because missing responses skew the sample, policymakers might dismiss warning signs and keep policy tight while parts of the economy are already folding inward.

This is not the sort of uncertainty that makes for healthy debate. It is the kind that invites narrative warfare. One side will argue that any weakness is “statistical damage,” not an actual cooling economy. Another side will argue that the numbers are hiding pain, and the shutdown made the government blind on purpose. Both arguments will find an audience, because when measurement fails, belief steps in to do the job. That is how you get economic policy by vibes.

What makes it worse is that the shutdown did not occur in a vacuum. The economy was already jittery from policy uncertainty, with households trying to guess what happens next and businesses trying to anticipate the next headline. Uncertainty is a tax on confidence, and this shutdown added a new surcharge by messing with the country’s ability to measure itself. When the dashboard stops working, every bump in the road feels like a cliff.

There is also a quieter consequence that does not get enough attention. Data gaps do not land evenly. When the household survey is incomplete, the missingness can skew toward certain groups, regions, and situations. People with unstable housing, irregular work, language barriers, or multiple jobs are harder to reach even in the best conditions. When the system is disrupted, those are often the first voices to disappear from the sample. The result is not just incomplete data. It is incomplete data that can overrepresent stability and underrepresent fragility.

That matters because the labor market is not one market. It is a stack of labor markets wearing a trench coat. Some sectors slow first. Some regions crack first. Some groups get hit first. When the data that helps us see those differences becomes fuzzier, it becomes easier for leaders to talk about “the economy” as if it is one smooth, shared experience. People living through layoffs and reduced hours do not need to be told that the aggregate numbers look fine. They need a government that can see them.

Counting Pain Is Not Optional, It’s the Whole Job

There is a particular arrogance baked into shutdown politics, and it shows up in the way officials treat economic data as if it is a luxury. As if collecting the unemployment rate is a nice-to-have, like decorative lighting, rather than a core function of governance. The truth is that economic measurement is how a country knows whether its policies are working. It is how it allocates resources. It is how it identifies emerging crises. It is how it avoids overreacting to noise while still responding to real harm.

When measurement breaks, everything downstream breaks with it. You cannot manage what you cannot see, and you cannot claim competence while hiding behind missing surveys. Yet that is exactly what a shutdown invites: a temporary suspension of accountability that produces permanent confusion. It also produces a convenient fog. When the data is incomplete, it becomes harder to prove that anyone’s policies are failing. When the data is distorted, it becomes easier to cherry-pick what you like and ignore what you do not.

That is why this delayed jobs report is not just an economic artifact. It is a political signal. It tells you what happens when governance becomes performative, and basic administrative work is treated like a bargaining chip. The country is left with partial instruments, and then told to admire the bravery of those piloting the plane. The passengers do not feel brave. They feel like they are listening to engine sounds and guessing.

The irony is that the shutdown did not stop the economy from happening. People still lost jobs. People still searched for work. People still gave up searching. Hours were still cut. Hiring plans were still revised. None of that paused because Congress wanted to make a point. The only thing that paused was the government’s ability to measure and communicate what was happening, and that pause is not neutral. It changes behavior. It changes expectations. It changes markets.

When investors and businesses cannot rely on a clear read, they become more cautious. When households cannot trust that policymakers even know what is happening, they become more defensive. The economy tightens, not necessarily because conditions have collapsed, but because uncertainty eats appetite. That is how missing gauges can become self-fulfilling. A government that cannot count can still cause damage, because everyone else has to compensate.

A Jobs Report Should Not Feel Like a Guessing Game

The most unsettling part of this week’s release is how normal it is going to become if we accept it. It is easy to treat the data caveats as a footnote and move on. It is easy to joke about the government losing the clipboard. It is easy to shrug and say the numbers are still “useful.” But usefulness is not the standard we should be settling for when millions of people’s livelihoods hang in the balance. The standard should be competence, consistency, and the ability to see the country clearly.

A jobs report should not require the reader to mentally subtract the shutdown and then imagine what reality might look like behind the smudged glass. It should not force policymakers into arguments about whether weakness is real or a statistical artifact. It should not force markets to price both rate cuts and recession risk while also pricing the government’s capacity to do basic math. Yet here we are, turning routine economic measurement into an exercise in interpretation and faith.

What this report really reveals is the fragility of the systems we pretend are permanent. We like to believe there is a sturdy, neutral apparatus behind the scenes, quietly counting and tracking and ensuring that when trouble arrives, someone will notice. The shutdown exposed that apparatus as vulnerable to political theater. It also exposed how quickly a country can slide from arguing about policy choices to arguing about whether the instruments are even working.

This is a dangerous place to live, because it creates a market for denial. If the data is incomplete, leaders can claim uncertainty as cover. If the data is distorted, leaders can claim ambiguity as innocence. If the data is late, leaders can fill the gap with whatever narrative serves them. The public is left to navigate between competing stories, each insisting it is the only honest interpretation of a report that admits it is missing key pieces.

The Gauge That Went Missing Was Trust

In the end, the most important number in this story is not job growth or unemployment. It is the number of people who will stop believing the government can accurately count what is happening to them. Once that trust goes, even good policy becomes harder, because the public does not accept the premises. Once that trust goes, bad policy becomes easier, because the fog provides cover. And once that trust goes, the next crisis becomes more dangerous, because the country enters it already divided on reality.

The shutdown did not just freeze parts of government. It shattered the routine signals that keep a modern economy from spiraling into rumor and fear. It took a boring, reliable process and turned it into a credibility test. And it did all of that while insisting the real emergency was political leverage, not public capacity.

The Ledger They Keep “For Later”

A delayed jobs report with missing gauges is not just an inconvenience, it is a warning. When the government cannot fully run the survey that tells us who is working, who is out, and who is quietly disappearing from the labor force, it is not merely failing at paperwork. It is failing at recognition. The country’s pain does not stop existing because the clipboard went missing, it just becomes easier to ignore, easier to misread, and easier to weaponize. The scariest part is not that we had to guess this week, it is that some people in power seem perfectly comfortable with the guessing.