When your dinner order starts to sound like a legal deposition, something has gone very wrong

There is a moment, somewhere between opening a menu and making eye contact with the waiter, when modern Americans are expected to perform confidence. We scan descriptions of leafy greens and artisanal toppings, nod thoughtfully at words like fresh and seasonal, and pretend we are not doing silent math about vomiting. This performance used to be optional. Now it feels civic. Because the truth, the quiet one that sits between the bread basket and the appetizer, is that eating in America has become a small act of faith in a system that keeps failing without ever fully admitting it.

Bill Marler does not perform that confidence anymore. He cannot. He is a Seattle-area attorney who has spent decades suing companies after foodborne illness outbreaks, and the cumulative effect of that career is not cynicism but menu discipline. Marler’s eating rules read less like preferences and more like evacuation procedures. No hamburgers. No leafy greens when eating out. No sprouts. No deli meats. Nothing precut. No bagged salads, no fruit cups, no veggie trays, no ready-to-eat meals. If it was washed, chopped, and sealed somewhere far away by people you will never meet, he does not want it.

This is not a personality quirk. It is muscle memory built from tragedy.

In the early 1990s, undercooked hamburgers served at Jack in the Box caused an E. coli outbreak that sickened hundreds of people and killed four children. The case reshaped food safety law, corporate practices, and the public’s relationship with ground beef. It also permanently rewired Marler’s understanding of what “normal” food can do to a human body. When you spend years reading medical records that start with diarrhea and end with funerals, hamburgers stop being nostalgic. They become suspicious.

If that history sounds dated, that is the uncomfortable point. The risk has not disappeared. It has migrated.

Marler’s caution now looks extreme only because the danger has shifted into places people were taught to trust. The modern foodborne illness story is no longer anchored to greasy burgers and sketchy diners. It increasingly lives in salad bags, produce bins, deli cases, and the refrigerated aisle of moral superiority. The foods marketed as light, virtuous, and convenient are now the ones most likely to betray you.

Consider the example that should have broken something in the national psyche but barely registered. A McDonald’s outbreak sickened more than 100 people and caused one death. The source was not the beef. It was onions. Not undercooked meat, not a drive-thru cliché, but a vegetable that exists primarily as a supporting actor. Onions are not supposed to be the villain. That is why the story matters. The threat is not always where culture tells you to look.

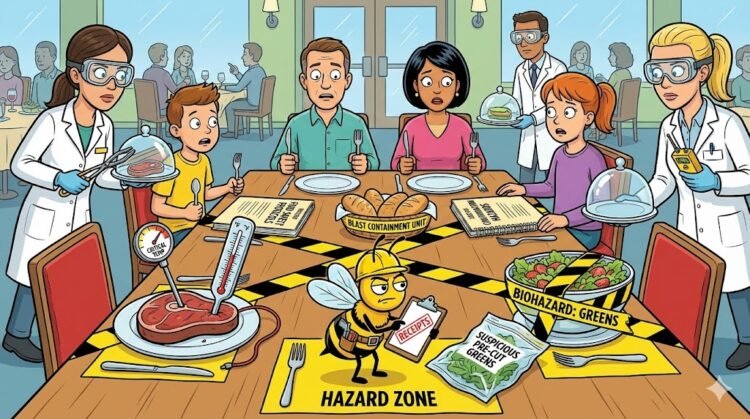

This is how Marler ends up ordering like he is filing a claim. At a Gordon Ramsay restaurant, surrounded by aspirational dining and carefully plated confidence, he orders a six-ounce filet cooked well-done with cooked vegetables. Not medium. Not medium-well. Well-done. Across the table, another lawyer orders a medium steak and a romaine Caesar, because that lawyer still lives in the America where salad equals safety and steak equals indulgence. The contrast is almost theatrical. Two professionals. Same restaurant. Completely different understandings of risk.

Federal health authorities try to make this manageable with numbers. Beef or pork to 145°F. Ground beef to 160°F. Poultry to 165°F. These temperatures are offered as reassurance, a kind of domestic engineering solution to a systemic problem. If you hit the right number, you have done your part. The chart implies that safety is a knob you can turn.

Marler sees those guidelines and does not feel reassured. He sees the gap between what the chart promises and what the system delivers. Cooking temperatures can kill pathogens in the meat you control. They do nothing for the lettuce that was washed in contaminated water, chopped on shared equipment, bagged, shipped, and displayed before it ever reached your kitchen. Temperature cannot unmix supply chains or undo cross-contamination that happened days earlier in a facility you will never see.

This is where the scale of the problem quietly undermines the comforting statistics people use to dismiss concern. Yes, the risk per individual meal is low. You can eat thousands of dinners without incident. That is true. It is also incomplete. Every year in the United States, an estimated 48 million people get sick from foodborne illness. About 128,000 are hospitalized. About 3,000 die. That is roughly one in six Americans experiencing illness annually, not because they made reckless choices, but because the system allowed pathogens to move efficiently from farm to plate.

Those numbers look abstract until you remember who absorbs the worst of it. Children under five. Pregnant women. Adults over sixty-five. Marler himself is now 68. When you age into the risk bracket, optimism stops feeling brave and starts feeling careless.

The most damning part is not that foodborne illness exists. Nature is messy. Bacteria are persistent. The indictment is that no one can say with confidence whether things are getting better or worse. Regulators and experts struggle to measure progress because most cases go unreported and most outbreaks are never traced to a specific source. People get sick, assume it was “something they ate,” and move on if they are lucky. The data dissolves into anecdotes and stomach aches.

A Government Accountability Office report did what GAO reports do best. It used calm language to describe a structural failure. Oversight of the U.S. food supply is fragmented across multiple agencies with overlapping responsibilities and inconsistent coordination. Translation: too many cooks, none fully accountable. When something goes wrong, responsibility scatters like seasoning.

This fragmentation creates a surreal dynamic where consumers are told to be vigilant while being given almost no visibility into the system they are supposed to trust. The burden of safety quietly shifts from institutions to individuals. Wash your hands. Cook thoroughly. Be careful. It is the public health version of telling people to bring their own life jackets onto a ship that insists it is seaworthy.

Not everyone in the field responds like Marler. That matters, because it shows how personal this calculation has become. Cornell food safety professor Martin Wiedmann describes his approach as “joy versus risk.” He still eats almost anything. He avoids hot buffets. He refuses beef tartare. He will eat street food if it is piping hot. Sprouts remain a hard no. His rules are looser, but they are still rules. Even the optimists have lines.

That contrast is revealing. Two experts. Two sets of boundaries. Neither believes the system is foolproof. They simply differ on where joy stops being worth it. The fact that joy has to be negotiated against microbial risk at all is the tell.

The American food system has optimized relentlessly for convenience, speed, and scale. Precut produce. Ready-to-eat meals. Centralized processing. Nationwide distribution. These innovations are sold as modern miracles, and in many ways they are. They also create single points of failure capable of sickening hundreds across multiple states before anyone knows there is a problem. Efficiency does not just move products faster. It moves mistakes faster too.

So dinner becomes a gamble, not in the thrilling sense, but in the bureaucratic one. The odds are good, but the stakes are uneven. Most people will be fine. Some will not. The system treats that as acceptable variance.

Marler’s story refuses to let that abstraction stand. Even with all his caution, even with a career built on identifying risk, he still got violently sick after a potluck in Idaho. No one ever found the source. That is the final irony. You can follow every rule, interrogate every menu, cook everything thoroughly, and still lose. The randomness is not a personal failure. It is structural.

This is where the satire sharpens into something colder. We live in a country where buying a salad can feel riskier than ordering a steak, where lawyers eat like bomb technicians, where federal guidance reads like a disclaimer, and where the most honest answer to “Is this safe?” is a shrug wrapped in statistics. The system has turned what should be boring into something fraught.

Dinner should not require a risk tolerance assessment. It should not ask you to choose between joy and safety like they are opposing values. It should not make professionals behave like paranoids just to feel normal. That it does is not a quirk of modern life. It is evidence of a food safety apparatus so disjointed that even the people who know it best do not trust it to do its job.

The Part They Hope You Miss

The quiet scandal is not that people still get sick. It is that we have normalized the idea that vigilance is a personal responsibility instead of a public guarantee. When a 68-year-old lawyer orders well-done steak and cooked vegetables in a fine dining room, he is not being dramatic. He is responding rationally to a system that made eating interesting when it should have made it boring.