When the memoir is less a reckoning and more a press release written in the font of a nervous breakdown.

The collapse of a reputation in Washington usually follows a predictable physics. There is the initial transgression, followed by the frantic denial, the inevitable leak of digital receipts, the forced resignation, and finally the exile to a podcast or a Substack where the aggrieved party can mutter about cancel culture to a paying audience of the similarly disgraced. But Olivia Nuzzi, the former star reporter who once chronicled the absurdities of the political class with a sniper’s precision, decided to chart a different course through the wreckage. After her career imploded in the wake of a “digital relationship” with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a scandal that managed to be both politically unethical and deeply weird, she did not go quietly into the night. She went into the literary fog machine.

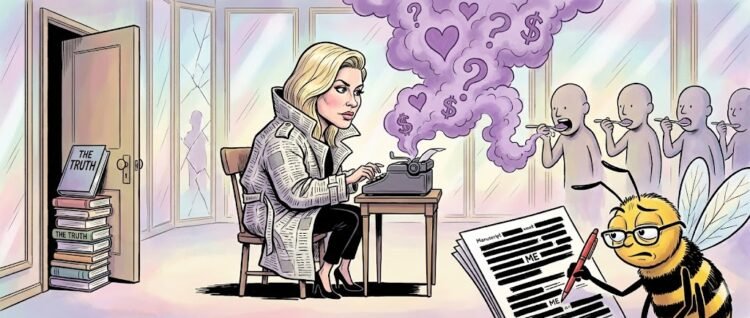

The result is American Canto, a memoir that lands on the shelves not as a book but as a strategic asset in a war for narrative survival. If you were expecting a clear accounting of how a marquee political journalist found herself entangled with a conspiracy-theorist candidate while simultaneously engaged to another high-profile political reporter, you have come to the wrong bookstore. This is not a deposition. It is a mood board. It is a 400-page selfie taken through a filter of vaseline and regret, designed to blur the edges of a scandal until it looks vaguely like art.

To understand the sheer architectural ambition of this book, you first have to appreciate the blast radius of the scandal that birthed it. Nuzzi was not just a reporter; she was a brand, a avatar of the new media ecosystem where the byline is bigger than the masthead. Her fall was spectacular. It involved the kind of messy, incestuous DC drama that usually stays confined to happy hour whispers at the Old Ebbitt Grill. There was the affair, or the “sexting,” or whatever euphemism we are using this week for sending intimate messages to a man who keeps a freezer full of roadkill. There was the fiancé, Ryan Lizza, a prominent journalist in his own right, who responded to the betrayal not with a quiet breakup but with a “dossier” of accusations and leaks that turned their private implosion into a public spectator sport.

It was a perfect storm of ethical failure, personal vengeance, and media navel-gazing. It ended her tenure at her magazine. It turned her into a punchline. And in a sane world, it would have prompted a period of quiet reflection. But in the content economy, quiet reflection is wasted inventory. So we have American Canto, a book that attempts to skip the apology tour and go straight to the literary canonization.

The critical reception has been, to put it mildly, confused. The legacy publications that Nuzzi once courted have described the book with adjectives usually reserved for a car crash involving a clown car. They call it “chapterless.” They call it “scattershot.” They describe a text that is less a narrative and more a collage of overheated metaphors and elliptical storytelling. The New York Times essentially asked if the editor had left the building. The Washington Post seemed unsure if they were reviewing a memoir or a prolonged panic attack transcribed by a poet with a concussion.

This stylistic incoherence is not an accident. It is the strategy. To write clearly about what happened would be to admit the banality of it all. It would require typing sentences like “I jeopardized my career for a digital thrill with a man who claims vaccines are a hologram.” That is a hard sentence to frame as a hero’s journey. But if you wrap that same reality in layers of pretentious imagery, if you talk about “the fractured self” and “the geometry of desire” and “the howling void of the campaign trail,” suddenly you aren’t a reporter with a conflict of interest. You are a protagonist in a Greek tragedy. You are Joan Didion with a data plan.

The satire here writes itself, but it is a dark, biting kind of comedy. The book positions the scandal not as a professional failure but as an initiation into a higher truth. Nuzzi presents herself as a woman traversing the underworld of American politics, collecting scars like merit badges. The sexting scandal becomes a plot point in a larger story about the soul of the nation, or the fragmentation of memory, or whatever high-minded concept was pulled from the grab bag of literary pretensions. It is a vanity project disguised as a confession, a PR purge masquerading as catharsis.

The writing itself seems intent on being misunderstood. It is dense with the kind of prose that sounds profound until you actually try to parse it. It is full of “glamourized suffering,” where every bad decision is reframed as a necessary step in the author’s evolution. The chaos of her personal life isn’t presented as a mess; it is presented as texture. It is the grit that makes the pearl. The problem is that the reader is left holding a handful of sand and wondering where the story went.

But American Canto is more than just a bad book. It is a monument to the collapse of boundaries that defines our current moment. We are living in an ecosystem where the line between the observer and the observed has been erased. Nuzzi was supposed to be the reporter, the one standing outside the arena taking notes. Instead, she jumped into the ring, got mud on her dress, and then tried to sell us a ticket to watch her clean it off.

The saga exposes the dirty secret of modern political journalism: it is often just another form of political participation. The reporters, the operatives, the candidates, they are all swimming in the same small, toxic pond. They date each other. They marry each other. They leak to each other. And occasionally, they sext each other. The pretense of objectivity was always a bit of a polite fiction, but Nuzzi took a flamethrower to it. And then she tried to build a sculpture out of the ashes.

The involvement of her ex-fiancé adds another layer of grim absurdity to the proceedings. The “Substack dossier” he released was a weaponized act of transparency, a data dump designed to maximize damage under the guise of setting the record straight. It was the “he said, she said” of the digital age, played out in real-time for an audience that treats human misery as content. Nuzzi’s memoir is the counter-strike in this asymmetrical warfare. It is an attempt to reclaim the narrative, not by disputing the facts, but by drowning them in purple prose.

This is the cycle of the modern scandal. First comes the exposure, the raw feed of embarrassing details that ricochets across social media. Then comes the professional consequences, the firing, the statement from the editor expressing “disappointment.” Then comes the book deal. The book deal is the crucial pivot point. It transforms the scandal from a liability into an asset. It allows the subject to monetize their own disgrace. It is the alchemy of the marketplace, turning shame into royalties.

Nuzzi understands this game better than anyone. She made her name by understanding the optics of power, the way image can supersede reality. Now she is applying those same lessons to herself. American Canto is a rebranding exercise. It is an attempt to shift her persona from “disgraced reporter” to “tortured artist.” It asks the reader to look past the ethical lapses and see the soul beneath. It asks us to believe that the real story isn’t the text messages; it is the feelings behind them.

But the “tell-nothing memoir” reveals the hollowness at the core of this enterprise. You cannot have it both ways. You cannot trade on your access and your insider status while simultaneously claiming to be a naive victim of circumstance. You cannot write a book about “truth” that refuses to answer the basic questions of “who, what, where, and why.” The result is a text that feels like a conversation with a person who is frantically trying to change the subject while maintaining intense eye contact.

The broader media dimension is equally damning. The fact that this book exists, that it was bought and published and reviewed, proves that we have lost the ability to distinguish between notoriety and importance. In the gossip economy, a scandal is just a form of engagement. It raises the profile. It clears the lane. Nuzzi is now more famous than she was when she was writing cover stories. She has ascended to the tier of celebrity where the reason for the fame matters less than the wattage of it.

This is the ecosystem that demands “transparency” but rewards spectacle. We say we want reporters to be honest, to show their work. But what we really want is drama. We want the messy breakup. We want the illicit affair. We want the “reckoning.” And Nuzzi is giving us the reckoning, packaged in a hardcover with a moody author photo. She is feeding the beast that ate her career.

The dark comedy of it all is inescapable. Nuzzi is cast as the star of a tragic-comedy whose script was written by patriarchy, careerism, and a collapsing news industry. She is playing the role of the “complicated woman” in a town that prefers its women to be simple. She is trying to write her way out of a hole that she dug with her own smartphone. And the only certainty in this show is that no one ends up readable, only marketable.

There is a biting mock seriousness to the way the industry treats these rehabilitation tours. The glossy interviews, the carefully curated excerpts, the panel discussions about “women in media.” It is all a performance. It is a way of sanitizing the grime of the scandal so it can be sold back to the public as a lesson. We are meant to nod solemnly and talk about “trauma” and “healing,” while ignoring the fact that the entire enterprise is built on a foundation of narcissism and greed.

In this culture, shame can be merchandised. Conscience can be commodified. And trauma can be turned into a brand relaunch. American Canto is the flagship product of this new economy. It is a book that doesn’t want to be read so much as it wants to be witnessed. It wants to be seen on the coffee table as proof that the owner is engaged with the “discourse.” It is a prop in the theater of the self.

The “chapterless” structure that critics mock is actually the perfect metaphor for Nuzzi’s situation. There are no chapters because there is no arc. There is no beginning, middle, and end. There is only the churn. There is only the endless, chaotic present where the only goal is to stay relevant for one more news cycle. The book is scattershot because the life is scattershot. It is a collection of fragments held together by ambition and glue.

The irony is that Nuzzi, who made a living dissecting the performative nature of politicians, has become the ultimate performer. She has become the thing she used to mock. She is spinning, pivoting, and framing, trying to control the lighting on a stage that is collapsing beneath her feet. She is writing about “truth” in a way that feels entirely synthetic.

We have to ask the question: Does American Canto redeem Olivia Nuzzi? Or is it a spectacle that suggests in our era, reputation isn’t repaired with truth, it’s just reissued under a softer cover?

The answer seems fairly obvious. Redemption requires a kind of honesty that this book seems allergic to. It requires looking in the mirror without the vaseline filter. It requires admitting that sometimes, you aren’t the hero of the story. Sometimes, you aren’t even the victim. Sometimes, you are just the person who blew it.

But admitting that doesn’t sell books. It doesn’t get you the glossy profile. It doesn’t get you the “comeback.” So instead, we get the smoke machine. We get the metaphors. We get the “literary trauma.” We get a book that talks a lot but says very little.

The tragedy of American Canto isn’t that it’s a bad book. Bad books are published every day. The tragedy is that it works. It keeps the name in the lights. It keeps the checks clearing. It proves that in America, you can do almost anything as long as you are willing to write a memoir about it afterward. You can betray your profession, your partner, and your own standards, and as long as you can turn it into “content,” you will be forgiven. Or at least, you will be pre-ordered.

So here we are, reading the reviews of a book about a scandal involving a brain-worm candidate and a star reporter, wondering how we got here. We are watching the machinery of magazine journalism grind against the machinery of celebrity culture, producing a screeching noise that sounds a lot like a cash register.

Olivia Nuzzi wanted to write the great American memoir. Instead, she wrote the great American press release. She wrote a testament to the power of spin. She proved that with enough adjectives, you can bury anything. Even the truth.

The “tell-nothing memoir” is the perfect artifact for a “know-nothing” era. It is a book for people who want the feeling of insight without the burden of facts. It is a book for a world where the only thing that matters is the narrative, and the truth is just an optional accessory.

As the book tour rolls on and the hot takes pile up, the one thing that remains clear is that the boundaries are gone. Journalism, politics, entertainment, it is all just one big slurry of content now. And Olivia Nuzzi is swimming in it, doing the backstroke, waiting for the tide to turn.

She might not be a reporter anymore. She might not be a fiancée anymore. But she is an author. And in the end, isn’t that what really matters? The ability to put your name on the spine of a book and say, “I exist. I matter. Buy me.”

The final verdict on American Canto won’t be written by the critics. It will be written by the sales figures. And that, perhaps, is the darkest joke of all. We claim to hate the grift, but we always buy the ticket. We line up to watch the car crash, and then we complain about the traffic. Olivia Nuzzi knows this. She is counting on it. She has turned her life into a product, and business is good.

Receipt Time

The real cost of American Canto isn’t the $28.99 cover price. It’s the final shred of credibility for an industry that used to pretend it had standards. We are watching the complete commodification of the conscience. The receipt shows a charge for “Reputation Repair” and a discount for “Selective Memory.” The transaction is approved, the book is shipped, and somewhere in the distance, a bee buzzes around a discarded copy of the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics, wondering why it smells like expensive perfume and printer ink.