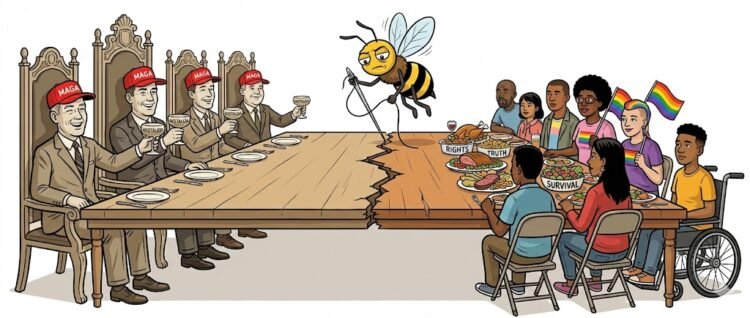

We gather here today, in the warm glow of incandescent bulbs and familial obligation, to perform the sacred ritual of forced gratitude. The table is set. The turkey is dry. The cranberry sauce retains the ridges of the can, a gelatinous monument to industrial efficiency. And around the perimeter, a collection of relatives—some beloved, some tolerated, some actively hostile—prepare to go around the circle and say what they are thankful for. It is a lovely tradition, in theory. But in 2025, the room is often divided not just by the centerpiece, but by red hats and a slogan that hangs in the air like a threat: Make America Great Again.

The demand of the slogan, and the demand of the holiday, is the same. We are asked to be grateful for the past. We are asked to look backward with misty eyes and celebrate a golden age of American prosperity and unity. But for many of us sitting at this table—the Black, the brown, the queer, the trans, the immigrant, the Jewish, the Muslim—that nostalgia is a trap. We are being asked to toast eras that were actively trying to erase us. We are being asked to pass the gravy to people who vote for policies that would strip us of our rights, all while smiling and pretending that “Again” was ever great for anyone who wasn’t a straight, white, Christian man with a pension.

So, let’s do a little time travel before we cut the pie. Let’s unpack the “good old days” decade by decade and see who got a seat at the table and who was on the menu.

Fifty years ago, in 1975, the country was supposedly in a better place. But if you were Black, you were living in the shadow of redlining, a federal policy that systematically denied mortgages to Black families and created the segregated neighborhoods we still live with today. You were fighting school segregation that had simply shape-shifted into “neighborhood schools” and white flight academies. You were watching the early gears of mass incarceration grind into motion, a machine designed to criminalize Black existence under the guise of “law and order.”

If you were Indigenous in 1975, you were still living through the era of the boarding schools. These were not educational institutions; they were assimilation camps designed to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Children were stripped of their language, their culture, and their families. The treaties signed by the US government were still being broken with the casual frequency of a New Year’s resolution. The land was still being stolen, the resources extracted, and the people silenced.

If you were Mexican American or Latino, the “good old days” meant English-only ordinances that criminalized your language in public spaces. It meant racist immigration sweeps like “Operation Wetback” (the actual government name) that rounded up citizens and non-citizens alike and dumped them across the border. It meant living in towns your ancestors built, on land that was Mexico before it was America, and being told to “go back where you came from” by people whose grandparents arrived at Ellis Island.

If you were Asian American, you were just climbing out of the shadow of the Japanese internment camps and the Chinese Exclusion Act, only to find yourself trapped in a new cage labeled “model minority.” This myth erased the poverty and struggle of Asian communities, painting them as a monolith of success to be used as a cudgel against other minorities, while simultaneously casting them as “perpetual foreigners” who could never truly be American.

If you were Jewish, the “golden age” was a time of deed covenants that barred you from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. It was a time of quotas at universities that limited how many of “your kind” could attend. It was a time of synagogue bombings and casual antisemitism that existed within living memory of the Holocaust. You were told you were “basically white and fine,” but the fine print always reminded you that your acceptance was conditional.

If you were Irish or Italian, your ancestors were the “invaders” of the 19th century, demonized as criminals, drunkards, and papist spies loyal to Rome. You were eventually allowed into the club of whiteness, but the price of admission was steep: you had to join in looking down on the next wave of arrivals. You had to trade your solidarity for status.

And if you were queer or trans? If you were like me? The “good old days” were a crime scene. In 1975, we were criminals. In 1985, we were dying of a plague while the President refused to say the word “AIDS.” We could be fired, evicted, or arrested just for existing. We lived in the closet not because we were ashamed, but because we wanted to survive. We watched politicians treat our lives as a punchline or a campaign plank, debating our humanity on the floor of the Senate while we buried our friends.

This is the history that sits at the table with us. This is the subtext of the “Make America Great Again” hat. It is not just a call for lower taxes or a strong military. It is a demand to return to a time when we knew our place. It is a wish for a world where we were quiet, where we were hidden, where we were grateful for whatever crumbs fell from the master’s table.

The emotional dissonance of Thanksgiving is the dissonance of loving a country that has not always loved you back. It is knowing that the jazz, the blues, the barbecue, the landscape, the very rhythm of American life are in your bones, while also knowing that the laws of this land were written to exclude you. It is loving the idea of America while surviving the reality of it.

In 1995, both parties were competing to see who could be tougher on “superpredators” and “welfare queens,” racist slurs disguised as policy that devastated Black communities. In 2005, Muslims and Sikhs were being harassed in airports and assaulted in the streets in the name of “freedom” and “national security.” In 2015, the Supreme Court had only just recognized marriage equality, a victory that felt fragile even then, while trans women of color were being murdered at staggering rates.

And here we are in 2025. The same people who benefited from every expansion of rights, the same people who never had to worry about which bathroom to use or whether their marriage would be dissolved by a court, now insist that teaching this history is “divisive.” They tell us that patriotism means pretending everyone had an equal shot all along. They tell us to be thankful.

So, we pass the gravy. We smile politely. We navigate the minefield of “how is work?” and “are you seeing anyone?” knowing that the honest answers—”work is hard because my industry is being gutted” or “yes, I’m seeing a man”—might trigger a rant about the woke mind virus.

But here is the twist. I am thankful.

I am thankful that I am here. I am thankful that I survived the closet, the conversion therapy, the addiction, the systems designed to break me. I am thankful for Matthew, my fiance, a man whose love is a daily act of defiance against a world that told us we shouldn’t exist. I am thankful for my chosen family, the friends who became brothers and sisters when blood ties frayed.

My gratitude is not the Hallmark version. It is not the soft-focus, unexamined thankfulness of the person who has never had to fight for their seat. My gratitude is gritty. It is hard-won. It is the gratitude of the survivor.

We are grateful because we know what it cost to get here. We know that every right we have was fought for, bled for, and died for by people whose names we might never know. We are grateful because we refuse to lie about the past. We refuse to pretend that the “good old days” were good for us. We refuse to accept the premise that “again” is a destination worth visiting.

Loving your country while it has not always loved you back is not a weakness. It is a superpower. It is an act of stubborn, defiant, deeply un-MAGA patriotism. It is the belief that America is not a finished product, not a museum of past glories, but a project that is still under construction. It is the insistence that we can make it better, not by going back, but by pushing forward.

So, when it is my turn to say what I am thankful for, I will look around the table. I will look at the red hats and the tight smiles. And I will say, “I am thankful for the progress we have made, and for the fight we still have ahead.”

And then I will take a second helping of pie. Because I earned it. We all did. The people who were told to be grateful for crumbs are finally eating the whole meal. And that, more than anything, is what terrifies the people who want to take us back. They know that once you have tasted equality, you never lose your appetite.

Receipt Time

The “nostalgia” for the past ignores the brutal math of exclusion. In 1950, the Black poverty rate was over 50 percent. In 1960, women could not get a credit card without a husband’s signature. In 1970, disability rights were nonexistent; there were no ramps, no accommodations, no ADA. The “greatness” was built on a foundation of legally enforced inequality. When we talk about “making America great again,” we are implicitly asking which of those laws we want to bring back. The answer from the red hats is often “all of them,” even if they don’t say it out loud. But we hear it. We hear it in the book bans, the abortion bans, the anti-trans bills. We hear the desire to return to a time when they didn’t have to share the table. But the table is ours now, too. And we aren’t leaving.