When redefining pedophilia becomes a primetime hobby.

There are moments in American media when you can almost hear the floorboards groan under the weight of a take so profoundly misguided that the English language itself tries to flee the room. Megyn Kelly’s latest contribution to the Jeffrey Epstein discourse produced exactly that sound, the slow creak of a structure deciding it has suffered enough. On her show, she unveiled a fresh distinction that no one asked for and no ethical universe needed. Epstein, she explained, might not have been a pedophile. He might have been into the “barely legal type.” Then she clarified her definition. “Like, he liked 15 year olds.” She paused just long enough for the nation to release a collective scream into a decorative pillow.

Kelly, who once carved out a persona as the cool headed lawyer mom who could interrogate power while maintaining her television ready sheen, now appears determined to build her own private diagnostic manual. When psychiatry texts define pedophilia, they use a constellation of criteria grounded in decades of research. Kelly uses a confidential source described as “somebody very, very close to this case” who knows “virtually everything” about Epstein’s dealings. According to this informant, Epstein was not a pedophile. He simply liked teenage girls. Preferably ones who looked even younger. Preferably ones who could blend in just long enough to avoid raising suspicion. Preferably the kind of minors whose existence makes every reasonable person want to fire the sun into the ocean.

Kelly admitted this was disgusting, a phrase she deployed as if self awareness could disinfect the sentence she had just said. To recap: Epstein, a man convicted of soliciting a minor and charged by federal prosecutors with running a trafficking enterprise centered on underage girls, was, in her retelling, less of a pedophile and more of a connoisseur of legal adjacent adolescence. According to her source, eight year olds were too young, fifteen year olds were his preference, and he wanted them to look older without actually being older. A kind of chronological Schrödinger’s victim.

It takes work to construct a taxonomy this warped. It takes even more work to present it as sober analysis. In a better timeline, the moment someone says, “Epstein wasn’t a pedophile, he was into fifteen year olds,” a giant hook descends from the ceiling and politely removes the speaker from the premises. In this timeline, it becomes an hourlong episode with audience engagement.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which Kelly waved aside with the breezy confidence of someone fact checking the tides, presents a very simple structure. To be a pedophile, one must experience recurrent sexual fantasies about minors, act on them or experience distress from resisting them, and be at least sixteen with at least a five year age gap from the child. Epstein, by every available public record, satisfied the criteria with the enthusiasm of a man filling out a loyalty card. The notion that the term does not apply because he preferred one section of the child age chart over another is the kind of argument that should dissolve upon contact with daylight.

Kelly insisted she was not making excuses. She was simply delivering facts. Facts curated from a mystery insider and filtered through her own instinct to reinterpret the entire concept of sexual predation into something more narratively convenient. Her tone hovered between prosecutorial and apologetic, a strange blend of journalistic distance and personalized rationalization. She even confessed that for a moment she had reconsidered her stance when Pam Bondi, Trump’s former attorney general, claimed the Justice Department had uncovered “tens of thousands” of videos of child sexual abuse material on Epstein’s computers. But Kelly quickly walked that pause back, declaring she could no longer trust Bondi’s word on the matter. The source of her newfound skepticism was left as a mystery, suspended in the air like a malfunctioning drone.

Her argument grew stranger from there. She said no one, to her knowledge, had claimed to be eight, or under ten, or under fourteen when they encountered Epstein. That, she suggested, reinforced the idea that Epstein’s crimes should be classified differently. Here Kelly leaned fully into the philosophical abyss, implying that certain subcategories of sex crimes involving minors are so structurally distinct that they require a gentler vocabulary. “There’s a difference between a fifteen year old and a five year old,” she said. The sentence clattered to the ground like a jar dropped in a kitchen. She followed it with a final flourish. “The whole thing is just disgusting.”

This logic resembles the ethical framework of a person who has spent too much time defending the indefensible and now wants credit for acknowledging that the indefensible still tastes bad. It is the moral equivalent of saying someone did not burn the house down, they merely doused the curtains.

Kelly’s entire theorem rests on the premise that pedophilia is a magic word whose application must be carefully optimized, lest we tarnish its conceptual purity. Her concern appears to be that Epstein’s crimes might fall into an adjacent category, one that is somehow less monstrous because the victims were teenagers rather than younger children. The implication hangs in the air. If exploitation is bad, exploitation of the very, very young is worse. And therefore exploitation of the slightly older but still legally powerless deserves a different label.

The real world does not cooperate with this taxonomy. The criminal codes do not distinguish between degrees of sympathy based on facial maturity or approximate grade level. Victims do not become less victimized because they had half completed algebra homework. Predators do not become less predatory because they preferred one demographic over another. Only someone looking for a conversational loophole would even dream of this distinction.

Kelly’s timing is not accidental. The release of Epstein related documents has reignited debate around his social circles, a constellation of billionaires, presidents, princes, scientists, and fixers. Each revelation drags a new name into the orbit. Bill Clinton flew on Epstein’s plane. Donald Trump was photographed with Epstein repeatedly. Prince Andrew settled a lawsuit relating to sexual abuse allegations. The criminal evidence compiled by multiple jurisdictions paints a picture of a wide reaching trafficking operation. In this context, attempts to massage the terminology feel less like intellectual inquiry and more like a last ditch effort to create narrative wiggle room for powerful men adjacent to the scandal.

Kelly herself endorsed Trump in the 2024 election, calling him a “protector of women,” a phrase whose irony should have triggered the nearest fire alarm. Her sudden investment in reclassifying Epstein’s predation reads as an extension of the same instinct. If the crimes are reframed as a category error, if the victims are repositioned as older than the worst imaginings, then perhaps the association becomes easier for certain political audiences to digest.

Bondi’s promises about releasing troves of Epstein information have, unsurprisingly, evaporated. The claim of “tens of thousands” of videos remains unverified. Her vow to unveil a “client list” has diminished into a procedural shrug. Yet the emails released by congressional Democrats tell their own story. Epstein communicated frequently with elites. Trump’s name appears in the exchanges. Kelly’s role in this broader information ecosystem is to curate the discomfort into something more palatable for her listeners. Not by denying the crimes, but by reinterpreting their classification.

The strategy is familiar. When confronted with overwhelming evidence of wrongdoing, redefine the wrongdoing. When the facts cannot be disputed, dispute the vocabulary. When the crimes are unambiguous, introduce ambiguity anyway. It is a rhetorical trick as old as scandal itself.

But this particular attempt reveals something darker. It signals a cultural moment where the impulse to protect political allies extends so far that even the age of the children victimized by a global trafficking ring becomes negotiable. Where common ethical boundaries are redrawn with the casual precision of a cable pundit revising her script. Where the priority is not truth, but narrative jurisdiction.

Kelly’s insistence that she is “just giving facts” is a masterclass in linguistic theater. She takes unverified claims, subjective impressions, and whispered interpretations and arranges them like evidence in a courtroom drama. The audience is invited to mistake the arrangement for substance. It is an old trick and a dangerous one, especially when applied to crimes that speak for themselves.

The truth is not complicated. Epstein targeted minors. He recruited minors. He trafficked minors. He committed crimes against minors. No amount of semantic tinkering alters the plain reality. The horror is complete without classification upgrades.

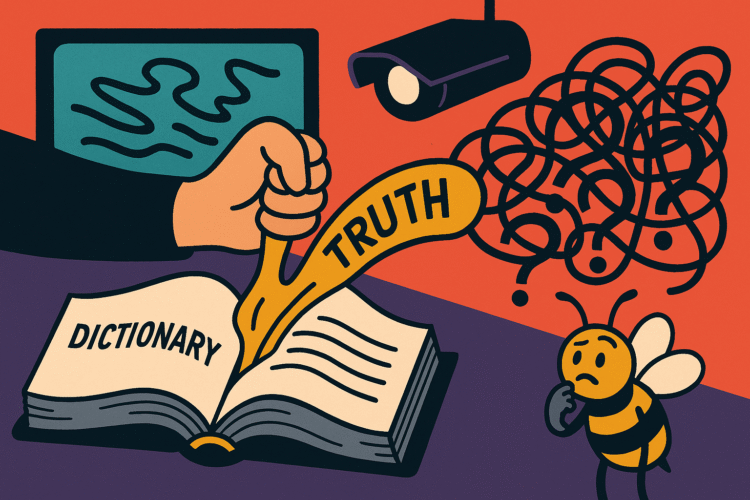

Truth, Shrunk To Fit

In the next wave of commentary, watch how quickly this reframing spreads. Watch whether pundits begin to adopt Kelly’s terminology as if it were a legitimate distinction. Watch whether the debate shifts from what Epstein did to what label makes the criminality less politically radioactive. And watch whether the public recognizes the tactic for what it is. When the facts become unbearable, some commentators try to shrink them. When the crimes become indefensible, they search for a smaller crime to defend instead. And when the truth becomes impossible to deny, they simply rename it until it fits in the palm of their hand.