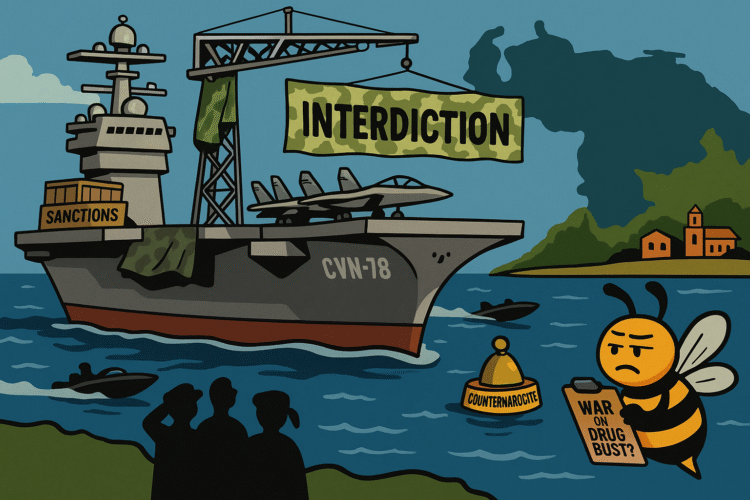

It should have set off every alarm instantly. A nuclear-powered supercarrier steaming into U.S. Southern Command’s zone under the pretext of “counternarcotics.” But if you look at the details it becomes clear this is not a fight against drugs. It is the opening act of war against Venezuela, dressed in the clothes of a patrol boat. The administration slammed a major military asset into the hemisphere with a wink and a nod and called it a timeline. That timeline is moving fast toward conflict.

Picture this: the USS Gerald R. Ford arrives with F-35s, a submarine, multiple destroyers, and a full strike group in tow. The mission? Push into the region where they say narco-traffickers hide. The reality? The regime the President has repeatedly said he wants toppled. Nicolás Maduro mobilizes troops, warns of “imperial invasion,” Colombia’s president withdraws cooperation, international bodies cry foul, and the Pentagon says everything is fine because it is “presence.” No one believes that anymore. Presence in the Western Hemisphere filled with warships is not neutrality. It is posture for impact.

The administration’s public line says the deployment is about transnational criminal organizations, drugs, protecting the homeland. But the asset doesn’t correlate. You don’t send the largest, most expensive combat vessel ever built to intercept go-fast boats or inspect fishing trawlers. That is like sending a battleship to handle jaywalking. The mismatch is so glaring it forces you to ask the question they don’t want you to ask: if the asset is mismatched, maybe the mission was mismatched too.

And the timing is not innocent. The President has made no secret of his desire to see Maduro go. He has praised coups of old, mused on regime change, asked advisers when “the night vision gear” was ready for Caracas. You don’t need a grand strategy to recognize signals like that. So when the carrier rolls in, the pieces line up: AV-8s, drones, destroyers, submarines, regional alarm. The function is not interdiction. It is intimidation. It’s war with fewer headlines but more risk.

Congress holds the war powers. The Constitution did not give the President solo rights to station a strike group offshore and then dispatch combat operations under the label “counternarcotics.” The War Powers Resolution says notify Congress within 48 hours of involvement in hostilities or imminent armed conflict. The legislation on counternarcotics is entirely different, and still requires coordination with partner nations and clear rules of engagement. But here the public sees neither briefing nor criteria. The carrier is just there. The region sees it just as well. And they do not infer traffic accidents. They infer threat.

The moment the Ford entered the waters of the Caribbean the region tensed. Maduro announced large-scale mobilization of forces. Colombia’s president pulled back from U.S. intelligence sharing. The CELAC nations issued statements about “unacceptable military coercion.” That reaction is not typical for a drug war. It is typical for a power play. A carrier doesn’t scare smugglers as much as it scares governments.

What this means in practice is alarming. Suppose operations commence against targets at sea, which are already being linked to “narco-terrorism.” Suppose F-35s fly missions from the carrier deck directed at Venezuelan coastal facilities or smugglers tied to the state. Suppose the narrative shifts gradually from “traffickers” to “state actors.” Then you don’t have a takedown of a criminal network. You have the first shots of a conflict.

The surge of military power has domestic cost too. The taxpayer picks up the tab for the carrier-group—and warships average hundreds of millions per month to operate. The opportunity cost: domestic infrastructure, social programs, missed. Meanwhile the region braces for an escalation, U.S. allies feel bypassed, an index of stability in the Western Hemisphere shrinks. The strategy of uncertainty replaces strategy of partnership.

We should call this what it is: an early execution of intervention doctrine disguised as drug policy. A war without declaration. A strike-force anchored off a friendly continent turned shaky. The President gets the optics of toughness. The region gets the unease of occupation. The international records get the precedent. The public gets the bill and the risk.

In the next 72 hours ask these questions: Will there be public rules of engagement published? Will Congress be briefed with documentation of authorizing law? Will we see signed diplomatic agreements with host nations? Will any federal agency release the list of missions the carrier will undertake? Will we see a shift from “presence” to “strike” in the official language? Because if we do not, then this entire convoy is not a counternarcotics operation. It is preparation for war.

The Ford is not a ship. It is a warning. And the question for every citizen should not be about the drug war. It should be about which war America is choosing to fight.