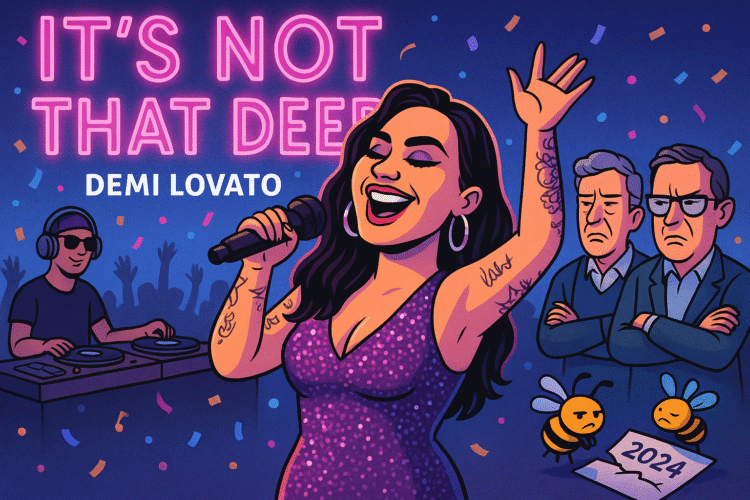

Pop critics love pain. They love a tortured confessional, a sonic therapy session, a bruised soul whispering about recovery under a single spotlight. The worse the heartbreak, the higher the Metacritic score. So when Demi Lovato drops It’s Not That Deep, a thirty-minute joy bomb of synths, sweat, and self-acceptance, you can almost hear a generation of reviewers blink in confusion and mutter, “But where’s the trauma?”

Rolling Stone tried to play it cool, calling the album “a carefree pivot back to pop euphoria.” Slant said it was “noisy and fun,” The Independent admired its “electronic gleam,” and Billboard dutifully tracked its rollout from teaser posts to radio-ready shimmer. Yet behind the polite applause, you can sense mild disorientation, as if Lovato violated an unspoken contract: she’s supposed to bleed for us, not bounce.

Apparently, joy still feels like a genre mistake.

The Audacity of Being Fine

Let’s start with the obvious scandal: Demi Lovato is happy. She got married, she’s sober, she’s stable, and she’s stopped treating microphones like confessional booths. She even titled her record It’s Not That Deep, which critics have treated less like an artistic choice and more like a cry for help. “It can’t really be that simple,” they say. “Surely there’s subtext.”

No, there’s a beat drop. That’s it.

Lovato’s ninth album is an unapologetic return to the club, the kind of gleeful, bass-forward project that doesn’t ask permission to have fun. Producer Zhone (a name that sounds like a password you’d forget but delivers precision pop craft) keeps everything tight and kinetic. Tracks like “Fast,” “Here All Night,” and “Kiss” hit with a clarity that’s both refreshing and defiant.

This is not a cry for help; it’s a victory lap. And in a pop landscape obsessed with “realness,” that’s apparently radical.

When the Deep End Becomes a Brand

Critics spent the better part of a decade demanding vulnerability from artists like Lovato, as if every record must double as an emotional affidavit. Holy Fvck was her answer to that demand: a rock-flavored exorcism full of pain, catharsis, and electric guitars that sounded like they’d been baptized in Red Bull. It was intense, personal, and exhausting.

Now, she’s traded confession for composition. She’s swapped journal entries for BPMs, traded “Let me explain my trauma” for “Wanna dance?” And the reaction has been half delight, half existential crisis.

Because pop journalism has a problem: it doesn’t know how to review happiness.

You can almost hear the confusion in the copy. Writers fumble for euphemisms like “light,” “shiny,” “frivolous,” “less emotionally charged.” Translation: “She seems fine, and we hate that for her.”

But maybe that’s the point. Maybe It’s Not That Deep is Lovato’s reminder that depth isn’t always about suffering. Sometimes it’s about skill, about knowing exactly how to construct a chorus that detonates in your bloodstream.

If you’re still looking for hidden pain in these songs, that’s your problem, not hers.

Pop’s Double Standard for Recovery

Male artists can release entire albums about cars, cocktails, or minor heartbreak and get labeled “existential.” But when a woman makes a record about joy, critics call it “surface.”

It’s an old story with new production credits.

Taylor Swift’s 1989 was once dismissed as “too polished.” Kesha’s High Road got a similar reaction after her bruising Rainbow. Even Miley Cyrus’s Endless Summer Vacation was called “emotionally opaque” because she didn’t cry into the mic.

Apparently, emotional regulation is a career liability if you’re female.

Demi Lovato knows that double standard better than anyone. She’s been public property since her teens, with every relapse, diagnosis, and identity shift dissected by strangers pretending to care. She owes us nothing, certainly not another ballad about survival.

So she didn’t write one. She wrote bangers instead.

“Popvato” and the Politics of Permission

Fans have dubbed this new era “Popvato,” a term that sounds like a Pokémon evolution but perfectly captures the mood: less confessional, more confident. Married life with Jordan “Jutes” Lutes clearly agrees with her. Gone are the apologetic interviews and trigger-warning disclaimers. In their place, we get glossy choruses and clean vocal stacks that sound like someone finally exhaled.

And the genius of it is that she’s not pretending this album is profound. She’s daring you to enjoy it anyway.

In interviews, Lovato calls this her “happiest era.” Critics have no idea what to do with that sentence. Happiness doesn’t test well. It’s not marketable. It doesn’t make headlines or pull quotes.

But it might just make hits.

The Zhone Blueprint: Joy as Engineering

Producer Zhone deserves an engineering award for capturing what Lovato’s voice can do when it isn’t tasked with dramatizing despair. Every song moves like a well-oiled machine: crisp, bright, and ruthlessly efficient. The beats are unrelenting, the choruses precision-timed, the hooks chemically addictive.

The record clocks in at just over thirty minutes, a rare act of restraint in an age when every artist thinks 90-minute tracklists are proof of genius. It’s Not That Deep respects your time. It’s the sonic equivalent of a neatly folded bedsheet: clean, deliberate, and quietly impressive.

This isn’t a comeback album. It’s an upgrade.

And that’s why the “lightness” of it all is a false read. Beneath the sparkle is control. Beneath the simplicity is skill. You can’t make something this effortlessly joyful without serious discipline.

Lovato’s finally learned that technical excellence is its own kind of vulnerability.

Critics Wanted a Confession, She Gave Them a Chorus

The reaction from critics reads like an accidental case study in projection. “It’s not that deep,” they say, meaning “we can’t make it about ourselves.”

Because confession invites analysis. Happiness just invites participation.

Critics want to interpret, not dance. They prefer symbolism to serotonin. But Lovato’s record is a dare to the think-piece economy: can you handle art that doesn’t need your commentary to matter?

The answer, judging from the cautious reviews, is “barely.”

But pop doesn’t care about your discomfort. Pop just wants you to move. And Demi’s giving you no excuse not to.

The Business of Euphoria

From a marketing standpoint, It’s Not That Deep is a masterclass in clarity. Every track feels built for TikTok loops, gym playlists, and car stereos. The runtime ensures you’ll play it twice without realizing it.

But more importantly, it proves that the “sad girl industrial complex” isn’t the only way to move units. You can sell dopamine too.

Lovato’s not chasing trends here. She’s correcting course. She’s showing younger artists that catharsis doesn’t have to mean collapse. That you can grow without groaning. That sometimes evolution just sounds like a clean hi-hat and a well-placed hook.

And that might be the most subversive message in pop right now.

The Fear of Uncomplicated Women

There’s something existentially threatening about a woman who stops apologizing for being okay.

Audiences have grown addicted to the spectacle of female suffering. We love a redemption arc, but only if it keeps looping. The second the protagonist stays healed, we lose interest.

Demi’s refusal to give us the drama feels like rebellion. She’s not rebranding; she’s opting out.

In a culture that still equates female worth with confession, a record that refuses to bleed is revolutionary.

The New Language of Depth

If Holy Fvck was about surviving the storm, It’s Not That Deep is about learning to surf. It’s not an album of statements, it’s an album of choices. Every tight beat and playful lyric is an act of artistic defiance against the notion that meaning requires misery.

Depth isn’t a synonym for darkness. Sometimes it’s precision, balance, and joy sustained over time.

When Demi sings about staying up all night, it’s not escapism. It’s embodiment. She’s finally living in the moment instead of narrating the aftermath.

The Real Joke: Critics Are Just Jealous

Let’s be honest: the real reason critics feel unsettled by this album is envy. Joy is rare, and they don’t trust it. They spend their days parsing metaphors and grading sincerity. Along comes Demi, declaring happiness as a thesis statement, and suddenly everyone’s scrambling for footnotes.

But joy doesn’t need citations.

It’s not that deep. It’s just good.

Why “Popvato” Matters More Than “Holy Fvck”

Every artist has their “serious” era, the one critics canonize because it sounds tortured. But longevity belongs to the ones who rediscover pleasure. Madonna’s Confessions on a Dance Floor. Gaga’s Chromatica. Carly Rae Jepsen’s entire existence.

Lovato’s It’s Not That Deep belongs in that lineage. It’s not the kind of record that wins awards; it’s the kind that wins over time. It’s the kind that soundtracks grocery store runs, road trips, and mental-health plateaus, the unremarkable moments that secretly define recovery.

Because real healing doesn’t happen in climaxes. It happens in routines. And It’s Not That Deep is routine at its finest: repetitive, rhythmic, resilient.

The Power of Refusing to Perform Pain

When Lovato decided to stop making music about her suffering, she risked irrelevance. That’s how our culture treats women who outgrow their trauma arcs.

But the irony is that in refusing to perform pain, she’s achieved something more radical than any breakdown narrative could. She’s proved that joy can be the point. That happiness doesn’t have to be an epilogue, it can be the plot.

This record doesn’t try to convince anyone of anything. It just exists, humming along in its perfect little 4/4 universe, refusing to explain itself.

And that’s the kind of defiance pop music needs right now.

The Closing Hook

In an age of overexposure, Demi Lovato’s It’s Not That Deep feels like the most intimate thing she’s ever done. Not because she tells us everything, but because she finally stops trying to.

It’s an album about boundaries disguised as bangers. A public statement of private peace. A reminder that growing up doesn’t have to mean slowing down, it can mean learning how to move differently.

So yes, the album’s title might sound like a joke, but it’s also a manifesto. A promise that depth doesn’t have to feel like drowning.

Pop doesn’t need to be profound to matter. Sometimes, it just needs to hit.

And Demi Lovato, against all odds, has finally given us what every overthinking listener secretly needs: permission to shut up and dance.