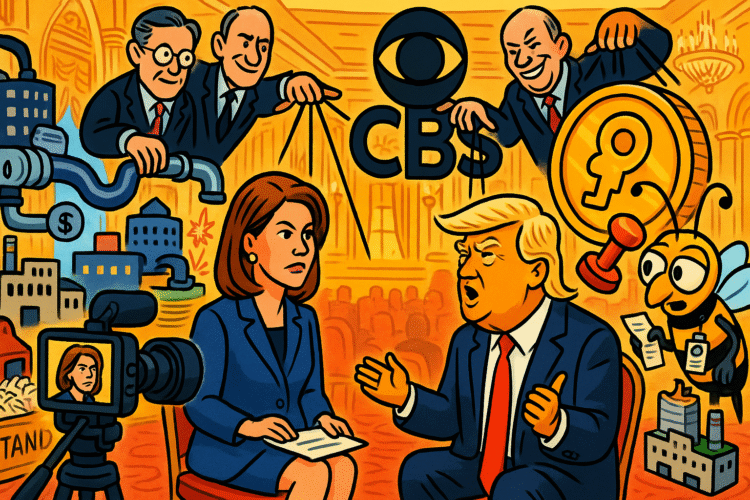

A president in a gilded ballroom sells tariffs as salvation and testing as deterrence, a network in a deal cycle sells the interview as a moon landing, and somewhere between the wand and the wine glass the public is asked to accept the headline as the truth, not the truth as the headline.

It begins with the décor. Not the microphones or the lighting grid, the décor. The gilded ceiling at Mar a Lago reflects everything, and reflection is the first trick of power. Say a thing, mirror it in lacquer and chandelier light, then ask the camera to capture the gleam. When Norah O’Donnell sits across from Donald Trump and asks what he received from a summit with Xi Jinping, the answer arrives like a catalog. No rare earth threat, a one year reprieve. Almost fifty percent tariffs, leverage and revenue simultaneously. Chips, not for you but for us. Factories that build their own power plants because the grid is slow, permits that ripen in weeks rather than years. Nuclear testing as a sign of strength because others are testing in secret. Eight wars ended. A ninth ready to fold if the parties would only admit they want to do business. Scrap the filibuster. End the shutdown on his terms. Violence is mostly the other side’s problem. The government works when the president does not have to explain himself.

Here is the performance inside the performance. On the surface, a head of state sits in a high gloss palace and selects talking points like cufflinks. Under the surface, CBS selects this room, this moment, this edit. Paramount’s corporate story hovers like a subtitle. Deals swirl. Layoffs hum in the background like the air conditioning, quieter than they feel up close. We are told by the president that he resolved a lawsuit with the show for a meaningful sum, and then we are told by the same mouth that the new leaders at the parent company are terrific. We can argue about the numbers and whether a settlement happened the way he framed it, but the larger shape is the point. Interviews are now instruments that test not only the tensile strength of facts, they test the tensile strength of the newsroom inside a merger.

Say the quiet part aloud. A consolidated media ecosystem that reports on a consolidated political ecosystem is not a watchdog at the gate, it is a dog on a moving walkway, and the walkway is controlled by someone else. If the White House would like a warm bath in major market households while the network would like a warm bath in quarterly earnings, the temperature rises on both sides without either hand looking guilty. The public watches steam and believes it is a weather report.

Let us take the claims as claims, not as verdicts, and watch how the incentives wrap around them like ribbon.

Tariffs first, because tariffs function in this telling as coin and cudgel. The president says an average near fifty percent is already in place, that he threatened a hundred percent surcharge and that this threat brought China to the table. He ties the threat to a specific concession, a rare earths reprieve, one year long, and then he translates the reprieve into an American ramp, partners in Japan and Australia and the United Kingdom, emergency programs, self sufficiency within twelve to eighteen months. The story flows like a trailer, peril then montage then triumph. In the montage, revenue pours in like a waterfall. Hundreds of billions in tariffs are not just defensive measures, they are proof that national security can be monetized.

A journalist, if one remembered the job is to measure rather than mirror, would open two windows. The first would show the regulatory record, the Federal Register entries that describe tariff orders in clauses and chapter numbers rather than adjectives, the effective dates and the scheduled sunsets, the specific commodity codes, the carve outs that turn a headline into a spreadsheet. The second window would show Treasury’s receipts, month by month, which is where claims about revenue go to live or die. That is not an argument against tariffs. It is an argument against letting the vibe of a number do the work of the number. Without both windows, viewers are asked to hold in their heads something we have been trained to accept for ten years. The president’s math exists because the president says it exists. What is strange is not that he says it. It is that major television allows the saying to stand without a paired visual that either affirms or contradicts the declaration. This is not an ethics seminar. It is page one journalism. Show the document. Show the ledger. Show the dates.

Chips next, because chips are the talisman of the hour. The president promises an American share of forty to fifty percent of the chip market within two years, then offers a theory of how that happens. The plants will build their own power, the permits will arrive in weeks, the export rules will block China from the most advanced Nvidia parts. In a country that would like to believe in industrial rebirth, this plays like a pep rally with a bulldozer. Here again a newsroom with its spine intact would stack the basic questions without flinching. What is the current market share by node and by wafer starts. Which specific export control rules, part numbers included, are being implemented by Commerce and enforced by Customs at ports, with what audit mechanisms and on what calendar. Which power plants tied to which fabs have permits in hand, what interconnections to which substations, and what workforce pipeline will staff them given the existing shortage of technicians and engineers. Two years is a political calendar. Semiconductors run on financing, workforce, and grid math. The distance between speech and solder is a chasm filled by procurement schedules and transformer lead times. If the interview is a test, it is not a test of presidential confidence. It is a test of whether a network will translate confidence into a checklist that any viewer can interrogate the next morning.

Then there is the suggestion that nuclear testing should resume, followed by a refrain that others are already testing in secret. A newsroom that remembers it is a newsroom would place a map of the law on the table. What authorizations would be needed. What appropriations. What environmental review under NEPA. Which tunnels are sealed and which can be reopened. Which monitoring regimes exist and which allies would react in what sequence. The difference between posture and policy is paperwork. The difference between television that makes you feel informed and television that makes you feel managed is whether the paperwork is named.

Now walk back to the meta script, because the room is the story. CBS is not a monastery in the mountains, enduring on tithes and silence. It is a division inside a conglomerate where debt matters, where deal terms matter, where the names of the executives matter because those names sign the budgets that fund the bureaus that give the correspondents their oxygen. One does not have to be a conspiracist to understand that coverage is shaped by who holds the purse and what story the purse wants to tell the street. The softer scandal is the simplest one. A company chasing a transaction needs friendly noise, so it produces programming that does not inconvenience the friendships that keep the transaction moving. It is possible to have a tough interview inside this reality. It is not common. The cruelty is quieter than that. The cruelty is the missing follow up and the unasked question about the numbers that matter.

The president adds his own flourish to the media plot by claiming he forced an edit in a prior cycle and received money in return, then smiles at the network’s new leadership, praises the parent company’s chief, name checks a newly installed editorial figure, then returns to policy. We are supposed to believe these are separate tracks. They are not. A source who is also a ratings event is a commodity. A company that is also a distributor of that commodity has incentives. A newsroom that is also a cost center has anxieties. The product is the interview. The buyer is the audience and the advertisers and the bankers. Everyone knows this. We pretend not to. Pretend is how trust erodes.

Grief feels out of place in a media critique, but it does not leave the room, because the room is also the last decade’s room. We have been trained not to expect consequence. A president says he stopped eight wars and the claim is set on the table next to the oysters. He says he will end the shutdown if the opposition votes like he wants, that he prefers the nuclear option to the filibuster because governing is easier without rules. He says political violence is mostly a problem of the other side, that the past indictments were proof of persecution, that crypto is national pride, that cities have been tamed by the new sheriff, that prices are down because the numbers say so. This is not just stump talk. It is a theory of how truth moves. Say it at scale. Repeat it inside a prestige frame. Let the platform’s authority become a power source for the sentence. If the newsroom does not immediately place the sentence inside a verification shell, the sentence becomes the superstructure of reality for those who want it to be so.

Here is the work a serious press would publish alongside the interview, not as scolding but as civic muscle. It would draw a ledger called verification targets. It would list rare earths and specify whether there is a binding agreement with named parties, a memorandum of understanding with signatories who can be held to account, or simply a statement of intent. It would list tariffs by product category and cite the legal authorities used, the dates of action, the estimated revenue, and the measured receipts. It would name Commerce rules on advanced chips, including the exact part families covered, the license thresholds, and the method of enforcement at export and re export. It would show a map of every announced chip fab in the United States, whether groundbreaking has occurred, whether utility interconnections have been approved, whether direct air capture of fiction has already taken place. It would layout the statutory steps for a new nuclear test and who would have to sign what before a shovel touched dirt. It would show Senate rule precedents for ending the filibuster, who has the votes, how quickly it could move, and what that power would likely deliver or destroy. It would publish an ombuds note explaining the edit, the standards, the agreements struck to secure the sit down, if any, and what would happen if any claim made on air proved false within a set time frame. It would treat the audience as adults. It would treat the subject as accountable. It would treat itself as a public trust, not as a brand extension.

Instead we drift through a culture of euphemism where the word news floats above the practice like a helium balloon, pretty, untethered, reusable. The audience, already exhausted, receives another hour of the familiar. A confident man in a palace. A polished interviewer with limited tools in a time slot with fixed ad breaks. A parent company chasing a target. A newsroom thinking about headcount. A country that wants a ledger and receives a vibe.

There is mock seriousness in pretending that this is new. It is not. The old order just had more layers, more editors, more time between a sentence and its broadcast. That time is gone, and so are the layers. You can see the skeleton now. Private equity and conglomerate debt snapped the connective tissue and called it synergy. Local bureaus were hollowed and called efficient. Standards desks were thinned and called modern. Ombuds offices vanished and were called legacy. And then we pretend to be shocked when a ratings event stacks up neatly beside a corporate event and both proceed as if the public’s oxygen is a rounding error.

Do not mistake this for a purity sermon. The press is a business and always has been. The question is not whether CBS pays bills or whether Paramount wants a clean quarter. The question is whether a newsroom inside a deal is allowed to act like a newsroom rather than a marketing arm. The evidence so far suggests that courage now requires paperwork, a checklist stapled to the broadcast, a rule that every claim is matched with a document within seventy two hours. The rule would accept that access has a price, then refuse to pay in silence. Publish the how. Publish the what. Publish the contradiction and call it by name. If the subject returns for a second sit down, good. If not, fine. The point of journalism is not to be invited back, it is to make the first invitation count.

The most damning plot in the interview is the smallest. It is the suggestion that the network itself once altered an answer, that money changed hands, that a legally meaningful event occurred and is now part of the lore. Whether the claim is true or not, one thing is clear. The viewers who need to know whether the program is a court of record or a stage show are not being served by a shrug. If the network has an ombudsman, let that person publish the chain of custody for edits. If the network has standards, let them be explained. If the network has nothing but a slick reel, then let us retire the word news from the logo and get on with the honesty of the market.

Return to the policy brags for a moment, because they are not harmless. When a president waves tariffs like a wand, a family hears price. When he invokes a border as a conquered frontier that now admits only those who come legally, a family hears fear. When he describes entire cities as tamed by force, a family hears permission. When he places his hand on the nuclear testing switch and says others are already doing it, a family hears normal. Journalism is the system that takes those words and runs them through the machinery that converts power into information. If the machinery is quietly unplugged because the production team has been trimmed or the lawyers have rewritten the playbook or the executive suite would prefer smooth water, then the words do not meet resistance, they meet choreography.

There was a quieter shock buried near the end, and it told you everything about how influence works when the cameras are polite. The president insisted he did not know the man he pardoned, the billionaire who ran the world’s largest crypto exchange, then nodded toward his own family’s crypto venture as proof that America is now number one in digital finance. He said the prosecution was a witch hunt, he said his sons know the space, he said the industry must live here, and the pardon was simply the right thing. The contradiction is not subtle. If you truly do not know the man you pardoned, but your family business closed a very large transaction tied to his platform, the conflict is not a matter of vibe, it is a matter of disclosure, paperwork, and public trust.

This is where a serious newsroom would stop the tape and widen the frame. Who met whom, when, and where. What the business relationship looks like on paper, not in slogans. Which company entities touched which wallets, what the deal terms were, who signed the documents, and what ethics reviews, if any, were performed inside the government before a pardon moved from idea to signature. If the pardon came first, why did the family deal follow. If the deal came first, why did the pardon follow. Either sequence is a story. Both sequences demand receipts.

The standard is not complicated. Public interest requires a record that separates private gain from sovereign power. That means calendars, emails, board minutes, escrow statements, beneficial ownership disclosures, and a clear timeline that aligns the pardon file with the money flow. It also means on-air transparency from the network about what it did to verify the claim that he did not know the beneficiary of his own clemency, while his family enterprise benefited from the same orbit. Access is not accountability until the questions reach the ledger. Until then, the country is asked to accept that a president can both plead unfamiliarity and profit proximity, and that the only thing that matters is the new storyline that crypto is patriotic because it is his.

Here is a less glamorous checklist for the days ahead, the one that serious citizens can keep in their pockets even if the network does not. Look to the Federal Register for the tariff orders, not the chyron. Look to the Commerce Department for the export control rule text that defines which chips move and which do not. Look to utility commissions and interconnection queues for the projects that claim to build their own power, because a press release does not wire a substation. Look to environmental reviews for any hint of nuclear testing, because a tweet is not a test plan. Look to Senate rule books and whip counts for any movement on the filibuster, because courage is counted in votes. Look to the Treasury’s monthly statements for how much money has actually been collected at the border. Demand that a network that lands this interview publish, alongside the video, a standards explainer that says what was promised, what was refused, and what the newsroom will do to verify every claim within a reasonable window. This is not heroism. It is the baseline.

The cynic in me, the one who learned over a decade that institutions bend when power leans, whispers that none of this will happen. Deal cycles will keep humming. Newsrooms will keep shrinking. Access will keep masquerading as accountability. A president will keep matching the room to the mood and the mood to the myth. But the realist in me knows a different fact. The only way to rebuild a press culture is to act like one, even when the incentives line up against it. That means reporters who carry documents in their pockets. Producers who say no to edits that cross a line. Executives who accept that one bad night of press is cheaper than a reputation that never comes back. And audiences who stop mistaking the room for the truth.

There was a question buried in Norah O’Donnell’s calm persistence that stuck with me. Why not say it plainly, the interviewer asked, when the subject implied a private understanding with Xi on Taiwan. The answer was the whole story and the end of it. I cannot tell you the secret, he said, the other side already knows. Power speaks to power in rooms where the rest of us are not invited, then walks into a gilded salon and asks us to take the hint on faith. Journalism was invented to break that pattern. If it does not, then we are back where republics go to die, not with a bang or a whimper, but with a sponsorship.

So here is the fuse, the one that ties the content of the interview to the content of the corporate story. When you reduce a press to an event business, events begin to behave like policy, and policy begins to behave like advertising. We are not watching an argument about facts. We are watching an argument about who is allowed to define what counts as a fact in the first place. If the gatekeepers are the same companies that need a clean earnings call, and if the most powerful guest in the world knows how to flatter the shareholders from the set, then the only safety left is the unglamorous discipline of verification. Publish the documents. Publish the rules. Publish the budgets. Publish the staff counts. Publish the edits. Publish the receipts.

Until then, treat the chandelier as a warning, not a light.